Meet the Presenters

This article is based on a webinar presented by STLE Education on Oct. 15, 2024. RP Coatings & Corrosion Inhibition is available at www.stle.org: $39 for STLE members, $59 for all others.

STLE member James Grabarz is product manager NA-SUL and K-CORR lines at King Industries, Inc. Grabarz has 30 years of work experience in the chemical industry with roles in quality assurance, research and development, technical services and sales and marketing with a focus in the fields of lubricant and grease additives. Grabarz has a master of science degree in chemistry from Sacred Heart University and a bachelor of science degree from Villanova University.

STLE member Wilson Zaabel started his career in the lubricants industry in 1981 as a quality control (QC) chemist with a grease manufacturer division of Pennzoil Products Co. Zaabel moved into industrial lubricant sales four years later with Pennzoil providing a wide range of lubricants and technical services to various industries, including steel mills, power generation plants, railroads and a myriad of manufacturing companies, distributors and OEMs. In 2000, Zaabel joined CITGO Petroleum Corp. and worked as product manager for greases and sales manager for private label greases. Zaabel joined Kyodo Yushi USA in 2013 as business development manager, global accounts, and from there Zaabel moved to King Industries in 2017.

You can reach Grabarz at jgrabarz@kingindustries.com and Zaabel at wzaabel@kingindustries.com.

James Grabarz

Wilson Zaabel

KEY CONCEPTS

•

This article explores the fundamentals of rust prevention and the mechanisms by which rust inhibitors protect metal surfaces.

•

It’s important to examine rust preventive formulation types and the key performance drivers that influence their effectiveness.

•

Testing methods, key applications, and emerging future trends in RP systems are reviewed.

The main focus of this article is on temporary rust preventive (RP) coatings. There are also paints that are considered to be permanent coatings, but this article does not go into details on that topic. In general, this article covers rust overview, introduction to RPs, RP test methods, RP systems and effect of base oil selection.

This article is based on an STLE webinar titled RP Coatings & Corrosion Inhibition presented by James Grabarz and Wilson Zaabel. See Meet the Presenters for more information.

What is rust?

There are very few systems that can completely exclude water. Rust degrades machinery itself and generates particulate abrasives that can cause wear. Without control, rust destroys the function and/or appearance of iron and steel, resulting in significant cost. In general, rust is an electrochemical process, and almost all lubricants will contain a rust inhibitor for systems that are primarily steel and where base fluids do not have a natural tendency to inhibit rust.

Corrosion and rust

Corrosion and rust are terms that are frequently used interchangeably. Corrosion is a more general term: Corrosion is the destructive alteration of metal caused by the chemical or electrochemical actions of its environment. On the other hand, rust is the oxidative corrosion of ferrous metals (iron and its alloys). Without control, rust can cause problems on metals by affecting function or appearance. In its nature, rust is an electrochemical process.

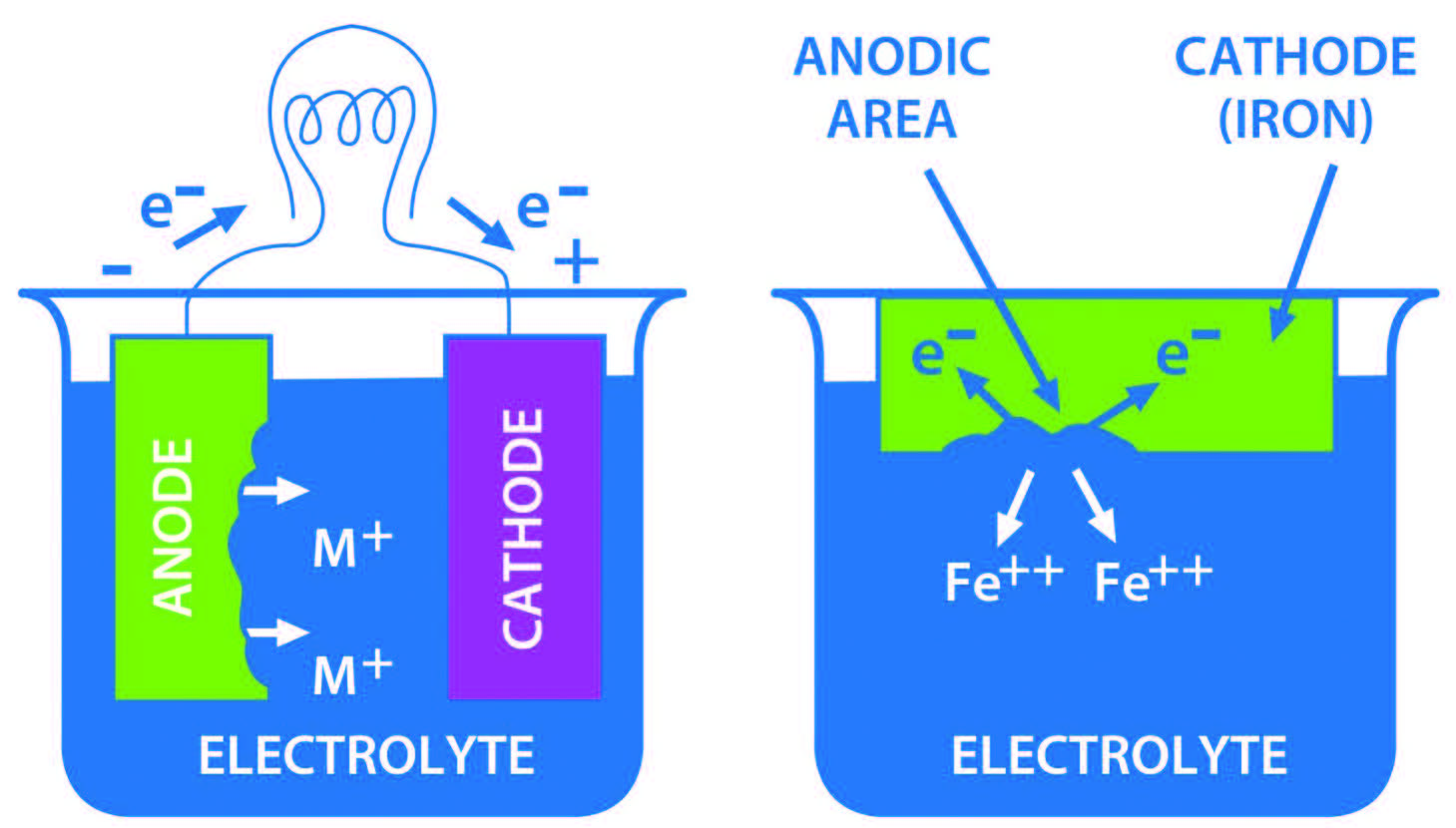

The electrochemical corrosion process

A corrosion cell is like a wet cell battery, that requires four essential elements:

•

Anode: high energy site of oxidation

•

Cathode: site of reduction

•

Electrolyte: a wet path between cathode and anode

•

Conductor: bridge between anode and cathode that completes the electric circuit

Figure 1 shows a basic electrolytic cell, shows anode and cathode and the flow of metal ions.

Figure 1. Basic electrolytic cell.

Figure 1. Basic electrolytic cell.

Iron/steel corrosion cell

A wet piece of iron/steel has the same four essential elements as an electric cell. Iron is a conductor, cathode and anode. Its reactive sites form anodes in areas where the surface has imperfections. There are grain boundaries in alloys, there are temperature gradients, physical stress is present, and there is electrical polarization. In wet path/water, the electrolyte is present.

The rusting process

In order for rust to happen all four cell elements must be present; if one element is taken away the rusting process can be stopped. Therefore, a wet piece of iron or steel contains all four of the elements of a corrosion cell. All four cell elements must be present in order for rusting to begin. Rust is inhibited by blocking or interfering with at least one of the elements and disrupting the cell. Polar chemical rust inhibitors prevent the electrolyte (water) and oxygen from interacting at the metal surface.

What are RPs?

RPs are temporary coatings formulated specifically to prevent the oxidative corrosion of iron: rust. Their film texture varies from soft, oily to waxy to polymeric. RPs are distinguished from “paints” by removability, as paints are generally considered permanent, and RPs are generally non-curing films. They may not have the intention to remove but could do so easily (solvent or detergent). RPs rely mainly on polar adhesion to the metal surface, generally higher rust inhibitor treat level than in liquid lubricants, 2%-15%.

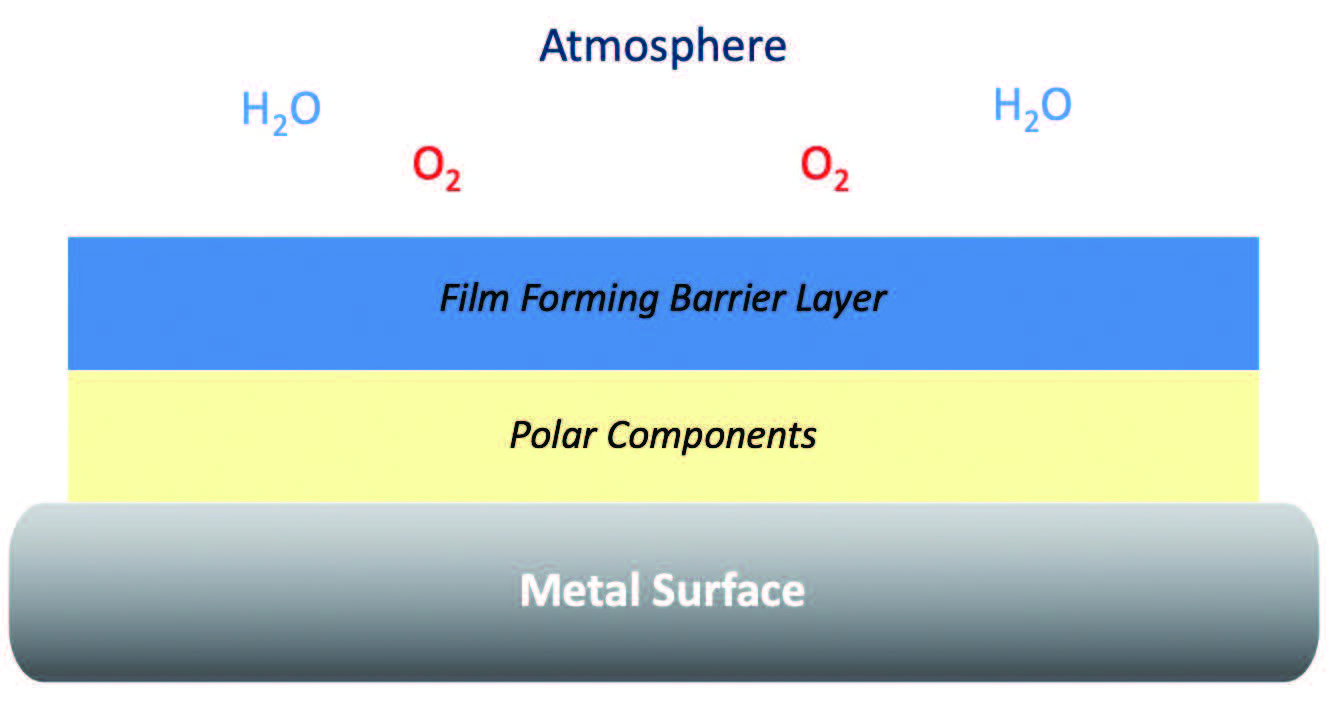

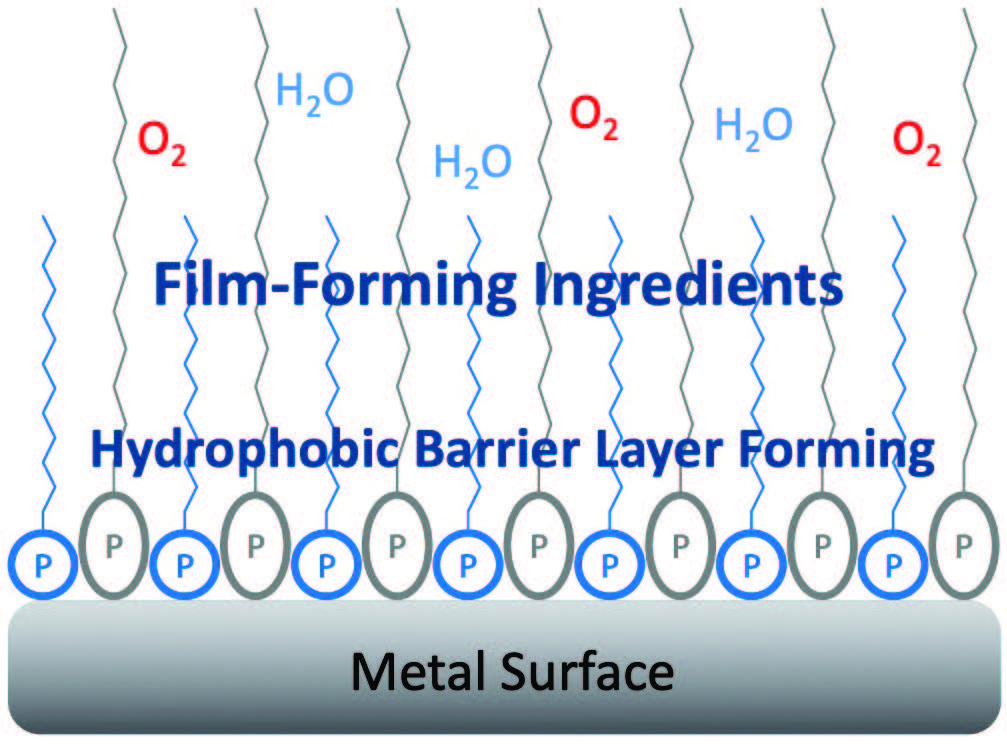

Figure 2 shows a typical representation of a RP film: On the bottom is the metal surface which is needed to be protected. Then there are polar components which align themselves with the metal surface; these also bring with them a film-forming barrier layer, and this serves to block oxygen and water from the atmosphere or the environmental conditions from contacting the metal surface breaking up those chemical pathways.

Figure 2. Representation of RP film.

Figure 2. Representation of RP film.

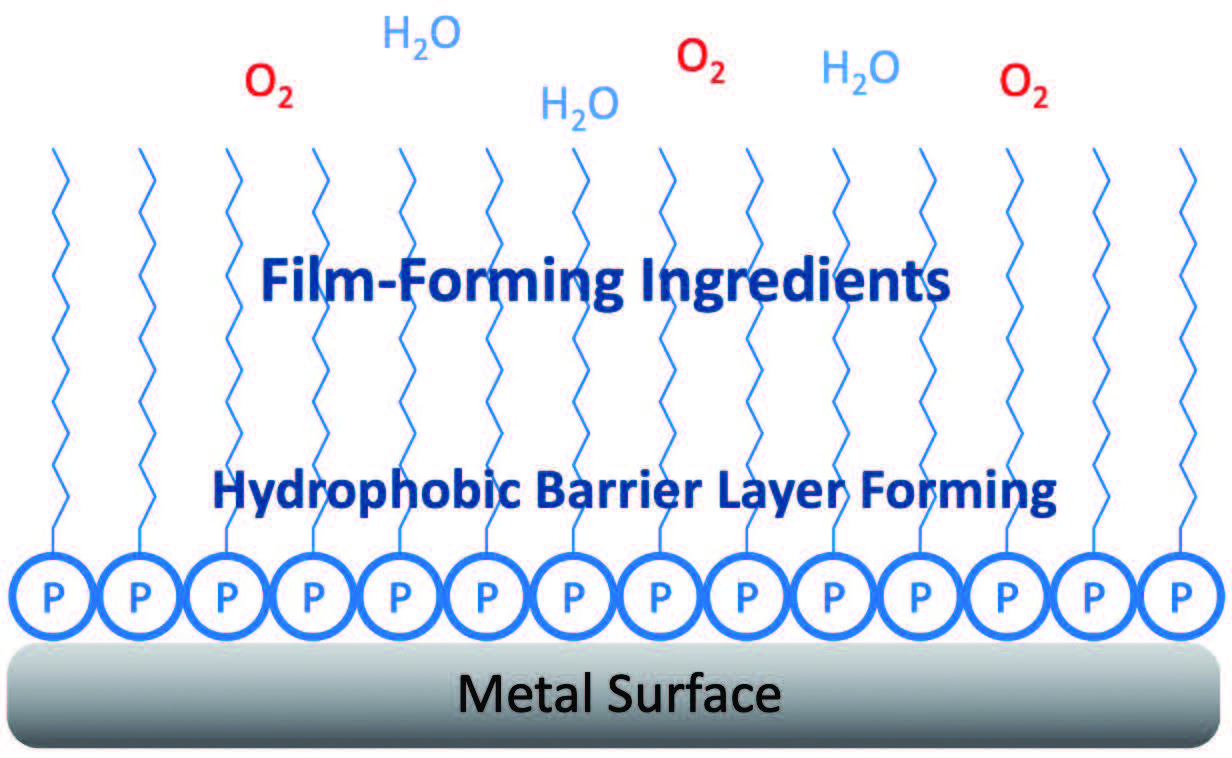

Figure 3 shows a tightly absorbed protective self-assembled mono layer with typical RP. The polar head of these molecules aligned with the metal surface, they usually bring along a hydrophilic tail which helps create a better film, leading to better performance. It repels oxygen and water from reaching the metal surface.

Figure 3. Tightly adsorbed protective self-assembled monolayer.

Figure 3. Tightly adsorbed protective self-assembled monolayer.

Out of all ingredients in common RP formulations the most important are the hydrophobic polar compounds, followed by the film-forming barrier ingredients (oils, waxes, resins, polymers). After that is the carrier, oil which is usually nonvolatile is a part of an RP formulation, and then usually most traditional RPs rely on a solvent, either a mineral oil solvent or a water-based solvent. Some special purpose additives can be used in an RP formulation such as coupling agents/emulsifiers, etc. The formula could include the following:

•

Hydrophobic polar compounds

•

Film-forming barrier ingredients

o

Oils, waxes, resins, polymers

•

Carrier – oil (nonvolatile), solvent or water (volatile)

•

Special purpose additives

o

Coupling agents/emulsifiers/solubilizers

o

Moisture displacers

o Acid neutralizers

o

Thixotropes

o

Dyes/pigments

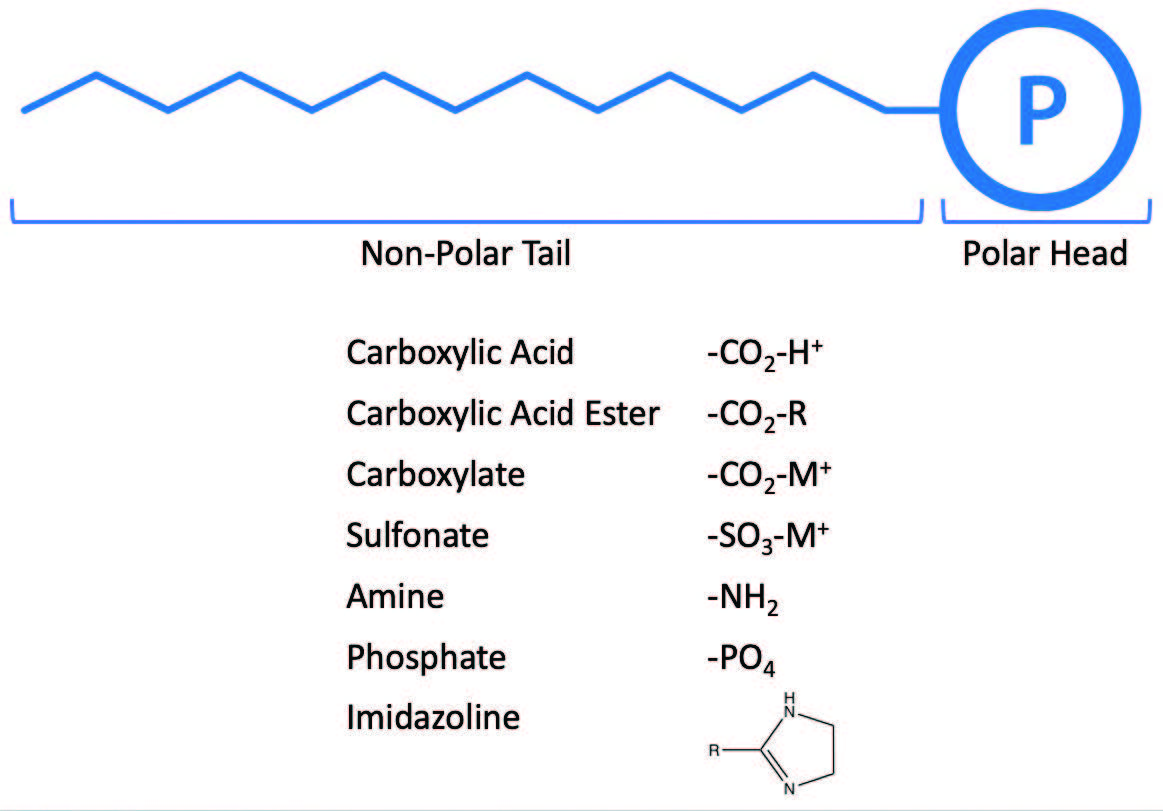

The surface active hydrophobic polar compound

(see Figure 4) usually consists of either.

Figure 4. Surface active hydrophobic polar compounds.

Figure 4. Surface active hydrophobic polar compounds.

Figure 5 illustrates the mechanism for rust inhibition. Hydrophobic layer and film-forming lipophilic tails provide a synergistic film. Sometimes a better film forms when there is a different variety of hydrophobic barrier molecules in it; these align closely on the metal surface giving a better barrier.

Figure 5. Mechanism for rust inhibition.

Figure 5. Mechanism for rust inhibition.

Factors to consider when formulating RPs

Some factors to consider when formulating RPs are the surface to be protected—need to know metal type, geometry, whether the part will be held vertically or laying horizontally, the substrate history and any kind of residues or imperfections that can translate and block the performance of the RP. Also, there is a need for an indication of a desired level of protection, which is usually measured in time or whether or not there is a need to meet special testing requirements. The coatings have certain characteristics that lend themselves to successful RP formulating such as oily, dry/non-tacky, self-healing and temperature resistance. Other key factors to consider are application and/or removal methods, color/odor, regulatory requirements and cost/performance.

RP test methods

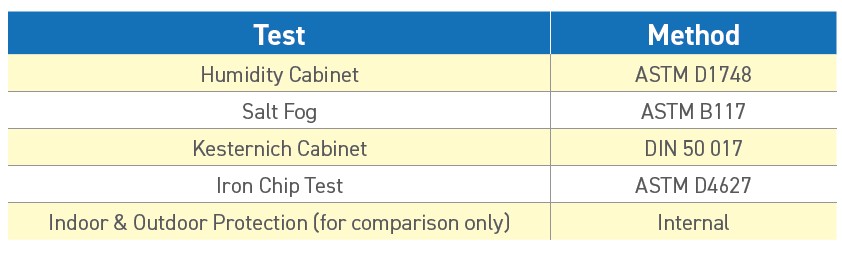

Some of the most widely used RP test methods are shown in Table 1.

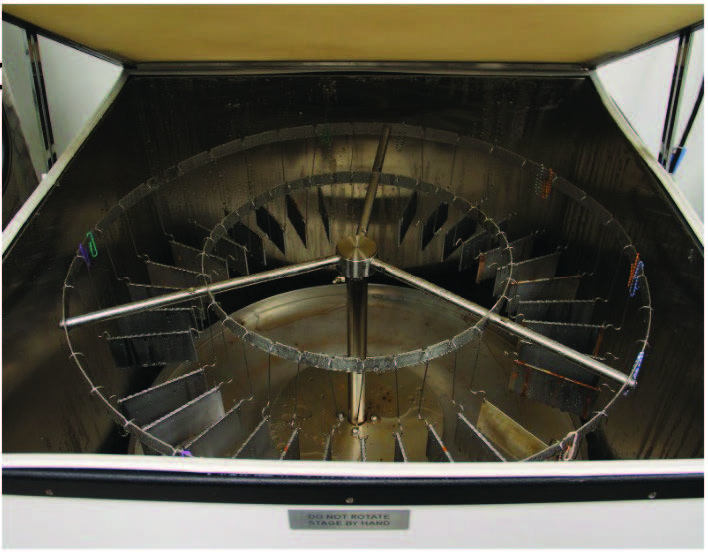

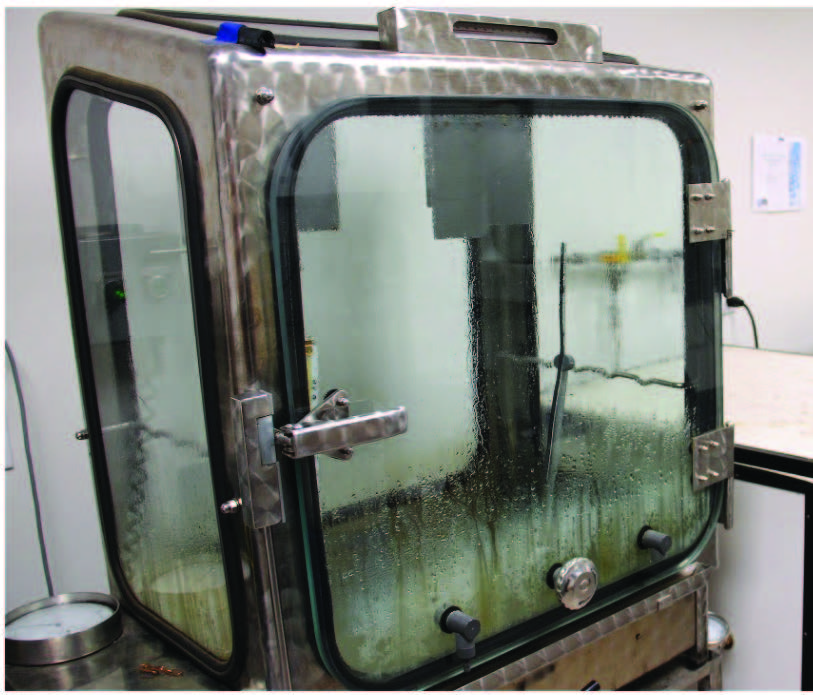

Humidity cabinet testing is run by a standardized test method, ASTM D1748 (see Figure 6). Cabinet design, panel preparation, chamber conditions and failure criteria are all well-defined. The chamber conditions are outlined in the method:

Humidity cabinet testing is run by a standardized test method, ASTM D1748 (see Figure 6). Cabinet design, panel preparation, chamber conditions and failure criteria are all well-defined. The chamber conditions are outlined in the method:

•

Air temperature inside cabinet: 48.9 +/- 1.1°C

•

Rate of air to cabinet: 0.878 m +/- 0.028 m3/h

•

Water in cabinet:

o

Level: 203.0 mm +/- 6.4 mm

o

pH: 5.5 to 7.5

o

Oil content: clear with no evidence of oil

o

Chlorides: less than 20 ppm

•

Speed of rotation: 0.33 r/min +/- 0.03 r/min

Figure 6. Humidity cabinet – ASTM D1748.

Figure 6. Humidity cabinet – ASTM D1748.

The ASTM D1748 failure criteria is clearly defined within the method. The significant area of each side of the test panel is evaluated and rated as follows:

•

Pass: The surface contains no more than three dots of rust, none of which are larger than 1 mm in diameter.

•

Fail: The test surface contains one or more dots larger than 1 mm in diameter or it contains four or more dots of any size.

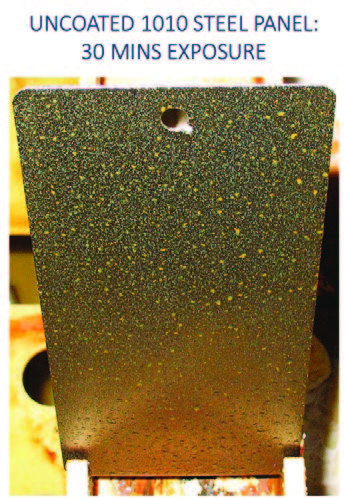

Salt fog – ASTM B117 is an accelerated method to differentiate rust prevention characteristics provided by a coating.

A cabinet

(see Figure 7) is held at 35°C while an aqueous 5% sodium chloride solution is continuously sprayed engulfing coated test panels, set on internal racks, creating an environment conducive to corrosion.

Figure 7. Salt fog – ASTM B117.

Figure 7. Salt fog – ASTM B117.

Figure 8a shows the salt fog chamber, and Figure 8b shows an uncoated steel panel after 30 min of exposure. It is important to note that ASTM B117 does not define failure conditions.

Figure 8a and 8b. Salt fog – ASTM B117.

Figure 8a and 8b. Salt fog – ASTM B117.

Figure 9 shows the Kesternich cabinet apparatus – DIN 50 017 method. The Kesternich test is used to evaluate the relative abilities of metal preservatives to prevent the rusting of steel panels under the conditions of 100% relative humidity at 50°C for eight hours followed by a 16 hour dry period under ambient conditions. The cycling is designed to test panels under more realistic conditions than 100% constant humidity. Panels are monitored for corrosion using the same failure criteria as salt fog.

Figure 9. Kesternich cabinet apparatus – DIN 50 017.

Figure 10 shows iron chips, from the iron chips test, ASTM D4627. This test method covers the evaluation of the ferrous corrosion control characteristics of water-dilutable metalworking fluids. In a disposable Petri dish, a piece of glass fiber filter paper is placed rough side up, then 5.0 mL of the diluted metalworking fluid and 4.0 grams of cast iron chips are added to the dish. The chips are fully submerged and evenly distributed. The dish is covered with its lid and allowed to stand for 20-24 hours at room temperature before draining the fluid and removing the chips. The filter paper is rinsed with running tap water for five seconds to remove any discoloration due to the fluid.

Figure 10. Iron chip test – ASTM D4627.

Figure 11a and 11b are showing a passing iron chip result

(see Figure 11a) when there is no rust stain on the filter paper. An example of a failure is on the right

(see Figure 11b). There are also other tests that could be used, e.g., outdoor sheltered and unsheltered test.

Figure 11a and 11b. Iron chip test – ASTM D4627.

Figure 11a and 11b. Iron chip test – ASTM D4627.

RP systems: Oil based

Advantages of oil-based RPs are that they are easy to apply, easy to remove, they don’t have volatile organic compounds (VOCs), they are self-healing films and also the coating itself can provide lubrication. Drawbacks are oily film, process cleanliness and oil mist.

Oil-based RPs are a preferred type of RP as they provide lubrication. Their typical applications include:

•

Storage of bearings and gears

•

Preservative (“slushing”) oils

•

Aerosol lubricants without solvent

•

Chain oils

•

Steel coil (mill oils), prelubes

•

Wire rope lubricants

RP systems: Solvent based

Advantages of solvent-based RPs are that RP ingredients are easier to dissolve, they have better performance than oil based, and they provide dry and thick coating for high performance. The drawbacks are flammability, low flash points and VOC, which leads to regulatory issues. Also, cleaning and removing may require solvents. Solvent-based RPs are used in the following applications:

•

Machined parts in process or transit

•

Automotive cavities and undercoatings

•

Preservation of steel in storage

o

Bearings, gears, tools, etc.

•

Aerosol RP/lubricant/penetrant

•

Marine coatings

•

Pipe coatings

RP systems: Oil and solvent based

There are also oil and solvent-based RPs. A combination of solvent with oil is usually much more effective than oil or solvent alone. Some benefits are as follows:

•

Films are more oily than with solvent alone.

•

Each additive has an optimum ratio of oil to solvent that is determined empirically.

•

The thickest films are obtained with intermediate oil/solvent ratios.

•

Salt fog performance is correlated with film thickness while cyclic humidity is not.

RP systems: Water based

Advantages of water-based RPs are that they are safe. They reduce fire hazards from hydrocarbon solvents and reduce worker exposure to solvents. They are better for the environment; they reduce hydrocarbon solvent emissions to comply with VOC regulations. Coatings can generally be removed with water/detergent, which further eliminates solvents. Some of the drawbacks are that they may require longer drying time. Fluid requires treatment before disposal. Some ingredients are difficult to use if insoluble in water. Formulation must form film to exclude water from metal surface. Despite these disadvantages excellent performance can be achieved. Some typical applications of water-based RPs are essentially the same as “solvent” based, but hydrocarbon solvents are eliminated.

RP systems: Hot melt RPs

Some advantages of hot melt RPs are that there are no VOCs. They provide a high level of protection (thicker films can be applied). Harder films and self-healing films are possible. Some drawbacks are that application requires elevated temperatures, and special equipment is necessary. Some typical applications of hot melt RPs include:

•

Solvent-free, dry, long-term protection of equipment and parts

•

Automotive (underbody, frames)

•

Long-term storage

•

Wire rope

Future trends

The future trends in RP systems indicate that ecological and toxicological aspects will become of increasing importance. Forthcoming VOC directives will emphasize environmental/health aspects and will require lower VOC limits. Thus aqueous products will become more popular. Dry, thin films less than 3 µm will gain popularity given they will be compatible with post treatment procedures.

Use of environmentally friendly vegetable oils and esters will gain more market share. Reduced film thickness will consequently induce a change in packaging material.

Electrostatical applications will be used more due to a lesser fluid used. The electrostatic method is much more efficient than the dip or spray methods (less waste, more efficient coverage).

The automotive and earth moving equipment manufacturers segments along with the steel industry will be the driving force of future RP technologies.

Effect of base oil selection: RP formulations

There are hundreds of RP additives available for formulations. Formulators take great care in selecting the right RP additive for a given application. However, they often overlook the effect of the base fluid and other additives on the performance of RP formulations. Internal studies of the presenters’ organization showed that the diluent has a major effect on the performance of RP formulations. Specifically, it was discovered that for all diluents tested with the same additive, the polished surface had longer hours to failure than the matte surface. The data also showed that the highly refined mineral oils gave worse RP performance than less refined mineral oils. The two tested naphthenic oils along with the Group I paraffinic oil performed best in salt fog testing. Vegetable and biodegradable diluents resulted in moderate performance. It was observed that the coating weight (thickness) did not seem nearly as important as diluent oil selection in this study.

Conclusion

The selection of the RP additive is critically important, but the selection of the diluent is of equal importance. It is critical to keep in mind that an RP formulation is a system. Each component must be optimized for maximum overall performance.

Dr. Yulia Sosa is a freelance writer based in Peachtree City, Ga. You can contact her at dr.yulia.sosa@gmail.com.