The main type of metal alloy used in high temperature applications (such as aircraft engine turbines) exhibits limited high temperature properties making them unsuitable for new designs.

A new, single-phase alloy, based on chromium, molybdenum and a minor addition of silicon, displays superior oxidation at high temperatures and is ductile to compression at room and elevated temperatures.

The introduction of a small percentage of silicon appears to be critical because this element enables a protective chromium oxide scale to grow slowly and minimizes oxidation of molybdenum.

The continuing objective to improve the performance and efficiency of machinery is leading researchers to work to aim on developing metal alloys that display the types of properties needed to meet specific applications. One such alloy class that is emerging is high-entropy alloys, which are prepared from single-phase materials that are prepared with equimolar amounts of multiple metal elements. This effort is in contrast to traditional alloys that are prepared from one dominant metal such as ferrous alloys based primarily on iron.

In a previous TLT article,

1 a theoretical study demonstrated a method for determining the physical and mechanical properties for over 370,000 high-entropy alloy compositions through the use of high-throughput first principles calculations. This analysis was conducted on alloys derived from 14 elements found in 3D printed and refractory high-entropy alloys that are two of the main types currently known. Elasticity properties for 1,900 of these alloys were calculated and found to be comparable to those determined experimentally. A public database has now been established containing the results from this study in order to facilitate development of new alloys.

Metal alloy development is also needed to design materials that can operate effectively at high temperatures. Efforts to improve the efficiency of high-performance equipment, such as turbines used to power aircraft engines and gas turbines, are leading to an increase in their operating temperatures to ranges near 2,000°C.

Professor Martin Heilmaier from the Institute of Applied Materials at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in Karlsruhe, Germany, says, “The design of new alloys based on refractory metals is based on their resistance to oxidation and to corrosion at temperatures above 500°C. These alloys need to have melting points near 2,000°C and also must exhibit some ductility at room temperature.”

Currently, the main type of metal alloy used in high temperature applications is nickel-based superalloys. Heilmaier says, “Challenges are encountered by users of these alloys because nickel-based superalloys are resistant to oxidation only to a maximum temperature of 1,100°C. Thermal barrier coating systems are applied to these alloys as they reach extremely high temperatures to protect against oxidation/corrosion and to reduce thermal conductivity. But the need exists for developing uncoated alloys that can withstand temperatures above 1,100°C to meet the challenging requirements of using high-performance equipment.”

Heilmaier and his colleagues have now prepared a new alloy that has superior high temperature properties at temperatures potentially above the 1,100°C maximum, which is the upper limit for using nickel-based superalloys.

Importance of silicon

The researchers initially focused on preparation of an alloy from chromium and molybdenum. Heilmaier says, “Our initial work involved preparing an alloy with a chromium to molybdenum ratio of 1.7 plus a minor addition of silicon. This alloy and the other alloys were prepared by an arc melting casting process. Oxidation testing at 1,100°C demonstrated that this alloy does form a protective scale at this temperature. While we previously considered working with other refractory metals such as niobium and tantalum, neither of them forms protective oxide coatings at elevated temperatures.”

A second parameter that is also evaluated by the researchers is pesting resistance. Heilmaier says, “Pesting resistance is a measure of an alloy’s resistance to disintegration in a furnace starting at a temperature between 500-600°C. Alloys with inadequate pesting resistance will initially start smoking in a similar manner to a chimney and then literally be converted from a solid to a gas in a process known as sublimation. In our testing of the alloy prepared from chromium and molybdenum only, evaporation of volatile molybdenum trioxide is observed at temperatures around and above 800°C.”

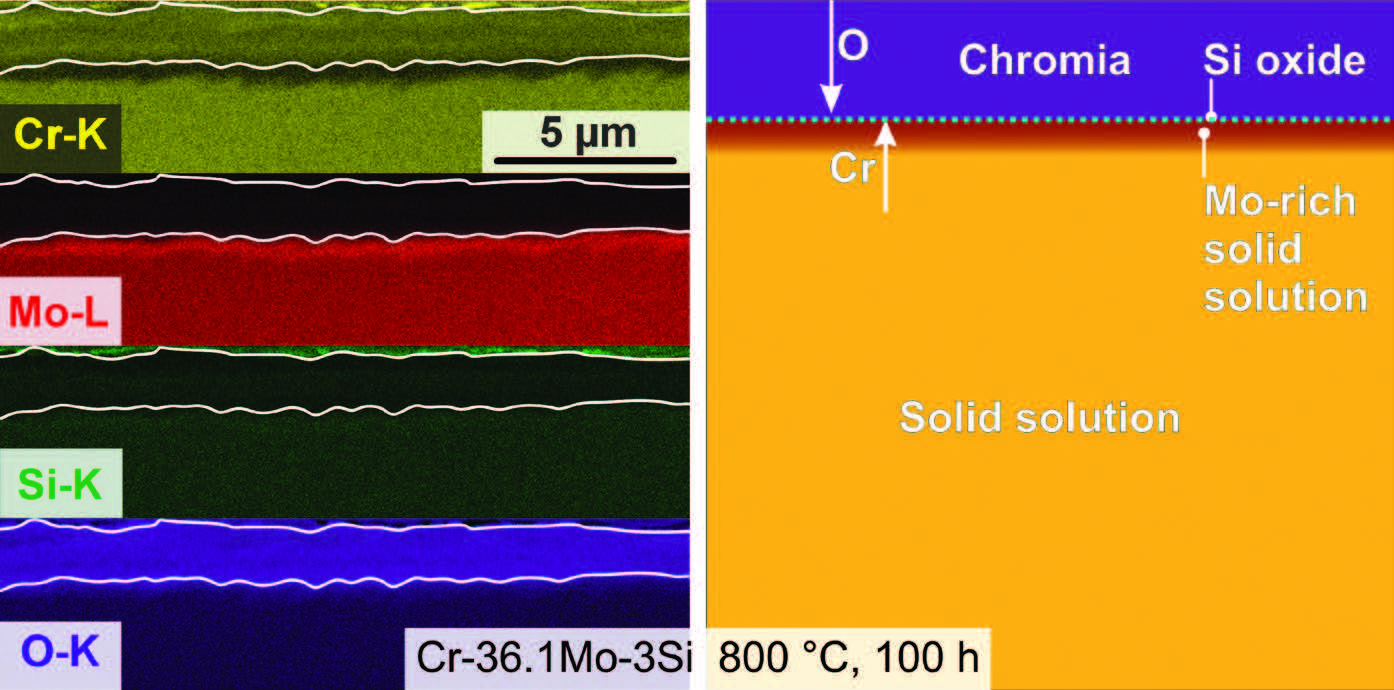

Introduction of silicon was found to be particularly significant due to the influence of this element in facilitating the formation of chromium oxide scale on the surface of the alloy

(see Figure 1). For this reason, the researchers decided to introduce silicon at a concentration of 3% to the alloy derived from chromium and molybdenum.

Figure 1. A single-phase alloy chromium, molybdenum, silicon alloy (Cr-36.1Mo-3 Si) alloy was oxidized at 800°C for 100 hours and remained stable due to the presence of an oxide scale as seen in a scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) on the left and a schematic on the right. Figure courtesy of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Figure 1. A single-phase alloy chromium, molybdenum, silicon alloy (Cr-36.1Mo-3 Si) alloy was oxidized at 800°C for 100 hours and remained stable due to the presence of an oxide scale as seen in a scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) on the left and a schematic on the right. Figure courtesy of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

The net result is the formation of a single-phase alloy that exhibits no evidence of oxidation after being subjected to heating at both 800°C and 1,100°C for 100 hours. Heilmaier says, “This alloy also displays a melting point that is estimated to be at or slightly less than 1,900°C which positions the chromium, molybdenum and silicon alloy to have the characteristics needed to be used at much higher operating temperatures for applications such as gas turbines than is currently possible for nickel-based superalloys. Silicon is important because this element enables the protective chromium oxide scale to grow slowly and minimizes oxidation of molybdenum. This is achieved through reaction with oxygen.”

True stress-true strain curves were conducted on the new alloy at room temperature and at 900°C by the use of compression tests. The new alloy was found to be ductile in compression at room temperature and at elevated temperatures. The strength of the alloy was retained at 70% of room temperature even at 900°C. However, while creep resistance still needs to be assessed, these types of alloys have historically demonstrated superior performance compared to nickel-based superalloys, especially when second phase particle strengthening is introduced.

The percentage of silicon used appears to be critical according to Heilmaier. He says, “We initially prepared an alloy with a silicon content of 13%. The two-phase alloy was found very oxidation resistant but brittle at room temperature thereby exhibiting no ductility.”

Heilmaier believes that the synthesis of this new alloy will open up new pathways for the development of metals that can be tailored to meet the high-performance requirements of applications such as in gas turbines with metal surface temperatures in the range between 1,100-1,300°C. Additional information on this research can be found in a recent paper

2 or by contacting Heilmaier at

martin.heilmaier@kit.edu.

REFERENCES

1.

Canter, N. (2022), “Designing high-entropy alloys,” TLT,

78 (11), pp 18-19. Available at

www.stle.org/files/TLTArchives/2022/11_November/Tech_Beat_III.aspx.

2.

Hinrichs, F., Winkens, G., Kramer, L., Falcăo, G., Hahn, E., Schliephake, D., Eusterholz, M., Sen, S., Galetz, M., Inui, H., Kauffmann, A. and Heilmaier, M. (2025), “A ductile chromium-molybdenum alloy resistant to high-temperature oxidation,”

Nature, 646, pp. 331-337.