Temperature-Dependent Lubrication Behavior of Choline Amino Acid Protic Ionic Liquids in Steel-Steel Contacts

Esmond Lau, Davis Kipkania Kiboi and Patricia Iglesias | TLT Scholarship Research March 2026

Editor’s Note: This month TLT profiles the 2025 recipient of The E. Richard Booser Scholarship Award, Esmond Lau (Rochester Institute of Technology). The scholarship is awarded annually to undergraduate students who have an interest in pursuing a career in tribology. As a requirement for receiving an STLE scholarship, students are given the opportunity to participate in a tribology research project and to submit a report summarizing their research. For more information about the Booser scholarship, visit www.stle.org.

Esmond Lau is a fifth-year student pursuing a combined bachelor of science/master of science degree in mechanical engineering and will graduate in May 2026. His research was conducted at the Rochester Institute of Technology’s (RIT) Tribology Lab, and under the mentorship of Dr. Patricia Iglesias. Outside of academics, he enjoys playing with LEGO® as a hobby and mentoring student robotic teams. You can reach him at el5963@rit.edu.

Esmond Lau

Abstract

Since conventional petroleum-based lubricants are becoming widely acknowledged for their harmful effects on the environment, it is imperative to develop sustainable alternatives. In this study, a family of choline amino acid protic ionic liquids (PILs) is developed using only renewable, biodegradable, and biocompatible products, aligning with the goal that addresses environmental impact. They are studied as additives to low-viscosity, non-polar base oil under steel-steel contacts. Both room temperature and high temperature conditions were evaluated to investigate the influence of temperature on the lubricating performance of choline amino acid PILs. It was found that incorporating 1 wt.% of choline aspartic acid or choline glycine as additives into polyalphaolefin (PAO) significantly reduces friction and wear loss under elevated temperatures, with friction reduced by up to 34.6% and wear by up to 48.3% compared with pure PAO under the same conditions. Additionally, Raman spectroscopy indicates the formation of oxide- and carbon-assisted tribolayer within the wear tracks, which provides protection. These results demonstrate the potential of choline amino acid PILs as effective for high temperature lubrication applications.

Introduction

Ionic liquids (ILs) have emerged as promising environmentally friendly lubricants and additives thanks to their excellent physico-chemical properties and the adsorption onto metal surfaces to form protective tribofilm layers [1, 2]. ILs are organic salts that are in a liquid state below 100°C. Their structure comprises ions with positive and negative electric charges. Unique properties of ILs include near non-volatility, non-flammability, and high molecular polarity. However, the cost of prospective ILs is high, and most used in current lubrication are composed of halogen-containing anions, which can form toxic acids when exposed to a moist atmosphere. Fortunately, past studies have shown that using ILs as additives to base oil significantly enhances friction-reducing and antiwear performance of the tribological components, demonstrating comparable performance to the neat ILs but at a much lower cost [1, 3]. In addition, a current trend gives attention to protic ILs (PILs), consisting of non-halogenated compounds and an easier synthesis route via simple proton transfer between the base and an acid [4]. Such an outcome facilitates the future design of ILs to be non-toxic and potentially be used in practical applications.

Choline amino acid PILs can be synthesized using only renewable, biodegradable, and biocompatible products [5]. In this study, the cation remains constant, while the amino acids with different side chains for the anions are explored. The base (choline hydroxide) provides the framework for strong hydrogen bonds, and an acid (amino acid) offers building blocks for lubricating films while generally being less toxic than other organic compounds. In this work, a family of choline amino acid PILs is studied as a 1 wt.% additive to low-viscosity, non-polar polyalphaolefin (PAO) base oil under room and high temperatures in steel-steel contacts. The study observes the characteristics of PILs, accompanied by tribological testing and examination of the worn surfaces. The concept of choline amino acid PILs introduces a novel approach in developing high-performance and environmentally friendly lubricants that have yet to be deeply explored. While the focus on environmental friendliness is a driver, the study also yields insights on how molecular design can optimize lubricant behavior at the macroscale.

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Synthesis

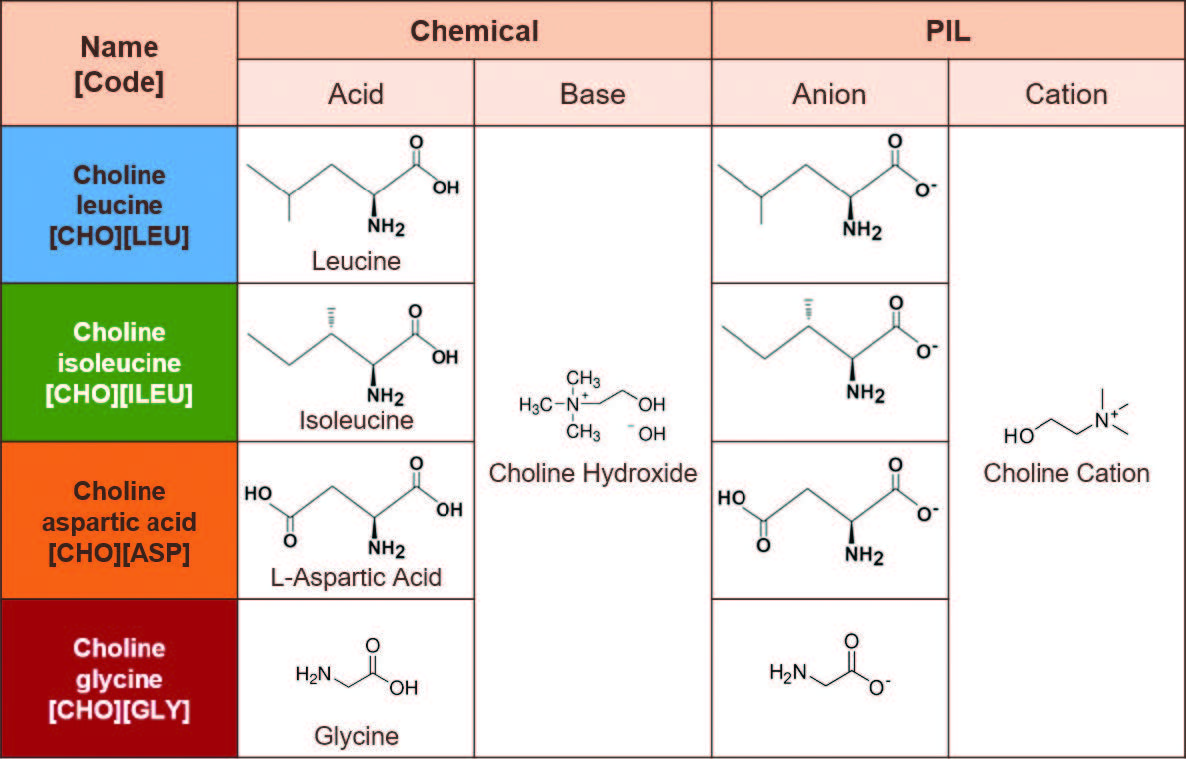

The four choline amino acid PILs for tribological testing were synthesized using leucine, isoleucine, aspartic acid, and glycine as the acids, and choline hydroxide as the base. A previous similar work has highlighted the materials and preparations of choline amino acids ILs [6]. In summary, aqueous choline hydroxide solution was added dropwise to one of the amino acids at room temperature, stirred at elevated temperature in an oil bath, and vacuum-distilled to eliminate residual water, yielding the final ILs. Table 1 demonstrates the cation and anion structures of the materials used for this work. These four amino acids represent structural differences, especially in their side chain structure, which will be useful to understand how they might behave differently under temperature changes. Some notable key features include flexibility (e.g., glycine is highly flexible for its minimal side chain), polarity (e.g., aspartic acid is polar and usually negatively charged due to an extra carboxyl group), and branching (e.g., leucine and isoleucine are slightly different regarding the position of one methyl group on their side chains).

Table 1. Molecular structure of choline amino acid PILs.

Low-viscosity PAO 4 is commercially available and serves as the base oil for this work. A mixture of 1 wt.% of each choline amino acid PIL was blended with the base oil through magnetic stirring and ultrasonic processing. They were stirred for 30 minutes and then for another 30 minutes for ultrasonication to ensure a homogenous mixture. As a result, four mixtures were created as follows: PAO+[CHO][LEU], PAO+[CHO][ILEU], PAO+[CHO][ASP], and PAO+[CHO][GLY].

1.2. Lubricant Characterization

The properties of each lubricant were investigated to characterize their potential behavior under testing conditions. The thermal stability tests were performed using the TA Instruments Q500 Thermogravimetric Analyzer. Each test of the 10 mg heated lubricant sample was conducted from 10°C to 600°C, with a constant heating rate of 10°C/min. The test was under a nitrogen atmosphere to ensure the surrounding environment did not interfere with the sample. The analyzer generates thermogravimetric curves data, recording each sample’s mass as a function of temperature, and assesses the sample’s thermal resistance.

Dynamic viscosity tests were performed using the Discovery HR-2 Hybrid (TA Instruments) equipped with cone-plate geometry. The rheometer records the sample’s viscosity from 25°C to 100°C, with a constant heating rate of 5°C/min and a constant shear stress of 20 MPa. The data provides the sample’s flow characteristics, examining whether they exhibit Newtonian flow.

1.3. Tribological Testing

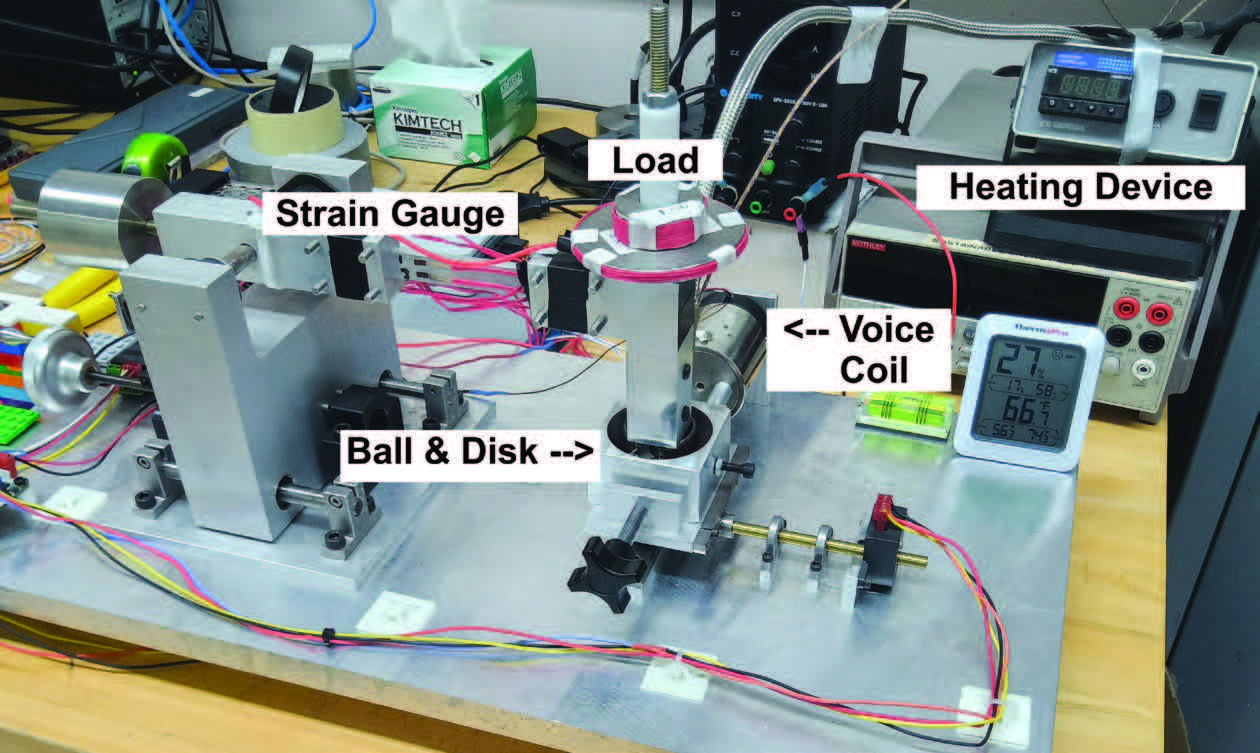

Using a custom reciprocating ball-on-disk tribometer with a full-bridge strain gauge configuration

(see Figure 1), the friction tests were run for each lubricant. For every test, 1.5 mm diameter AISI 52100 steel balls were placed against the AISI 52100 steel polished disks, with 2 milliliters of the lubricant added between the ball and disk. The steel disk was mechanically polished with a surface roughness of Ra averaged around 0.03 µm. All tests were performed with a controlled frequency of 5 Hz and a stroke length of 3mm. Over an hour, the total sliding distance reaches 108 meters. The application of a steady normal load of 3 N resulted in a maximum Hertzian contact pressure of about 1.51 GPa, as intended to operate the experiment under a boundary lubrication regime. Throughout the test, the coefficient of friction was continually collected every 0.05 seconds until 3600 seconds passed. To obtain repeatability, each lubricant mixture was tested three times, and the average value of the coefficient of friction was used for analysis.

Figure 1. Reciprocating ball-on-disk tribometer.

Figure 1. Reciprocating ball-on-disk tribometer.

All choline amino acid PILs were tested at room temperature (23°C) and high temperature (100°C), with relative humidity between 30-50%. After the friction tests, the wear scars of the steel disk are examined using the Olympus BH-2 optical microscope. The wear width was measured at 30 points across the length of the wear track

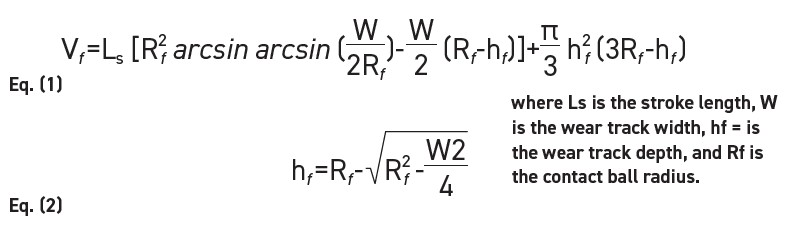

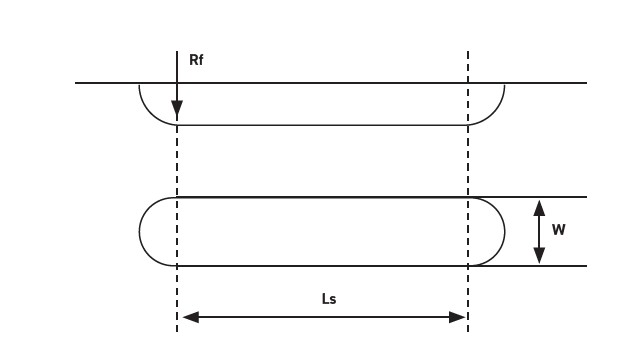

(see Figure 2). The average wear width was recorded and computed into Equations (1) and (2) to estimate the wear volume, as presented by Qu et. al [7].

Figure 2. Wear volume estimation.

Figure 2. Wear volume estimation.

For further worn surface characterization, a detailed analysis of the wear scars was conducted. The profiles of the 3D wear profiles were scanned using the VR-6000 optical (Keyence Corporation) profilometer. The profilometer also provides a visual view of the wear volume and depth. The surface morphology, including material transfer and grooves, was examined using the Tescan-Bruker Vega 3 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). The elemental composition was done with the Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS). A detailed analysis of the tribofilm layers that may have formed during the experiment was conducted using Raman spectroscopy. The Raman spectroscopy may tell the lubricating mechanism of the layer.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physico-chemical Characterization

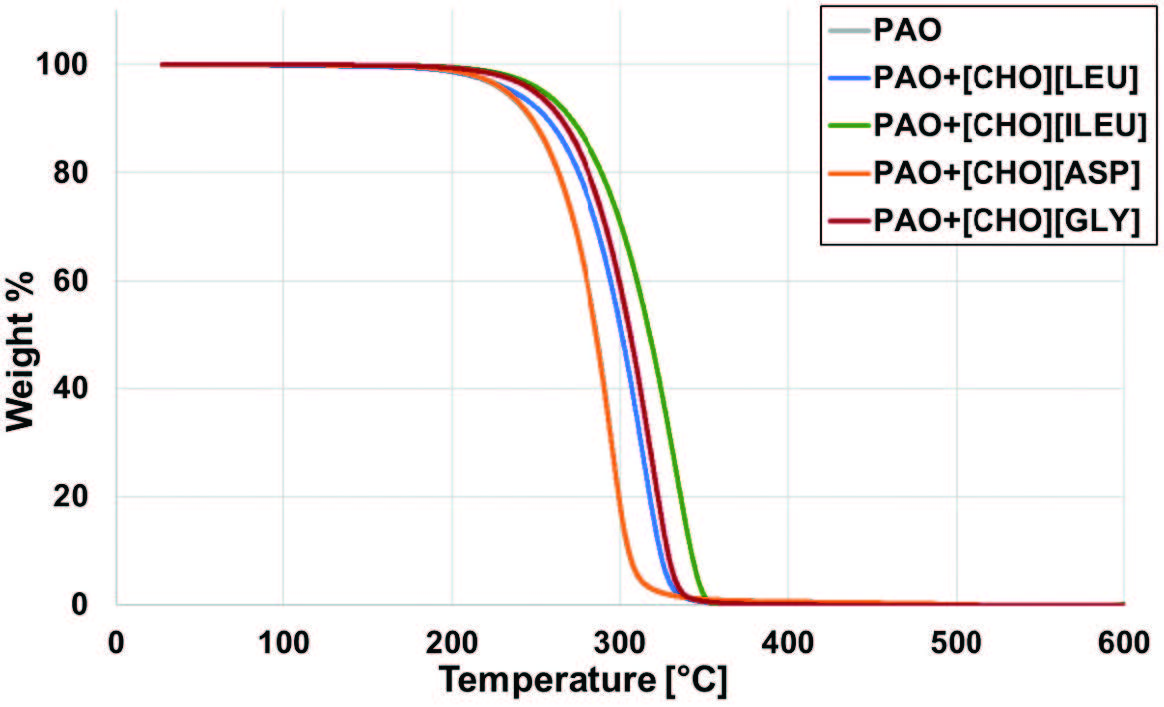

The thermal stability of the base oil and the four different mixtures is shown in Figure 3. Based on the degradation curves, all lubricants showed a single-step weight loss. Neat PAO starts to decompose at a temperature of 257.8°C, while the addition of choline amino acids PILs increases the onset temperature slightly. Particularly, the mixture PAO+[CHO][ILEU] has shown the highest onset temperature of 278.2°C, followed by PAO+[CHO][GLY] at 272.9°C, PAO+[CHO][LEU] at 264.1°C, and PAO+[CHO][ASP] at 258.3°C. In Figure 3, the curve of the mixture PAO+[CHO][ASP] overlaps the neat PAO, depicting no significant variations in the onset decomposition temperature.

Figure 3. Weight change of lubricants with temperature.

Figure 3. Weight change of lubricants with temperature.

The chemical structure of the amino acid anions was identified as a driver of thermal stability. Isoleucine is known to be highly hydrophobic due to its hydrocarbon side chain, which contributes to increased molecular packing and thermal resistance [8]. The subtle difference in the branching of leucine compared to isoleucine appears to alter physical bonding slightly, which directly affects the onset temperature of its respective mixture, although it remains hydrophobic. Glycine has the shortest side chain compared to all other amino acids. The absence of a bulky alkyl side chain in glycine allows its charged and polar groups to pack more closely, favoring stronger ion pairing and denser hydrogen bond networks. This more compact supramolecular structure can contribute to higher thermal stability [9, 10]. PAO+[CHO][ASP] demonstrated to be the least thermally stable of the mixtures. The extra polar carboxyl group of aspartic acid may have facilitated earlier decomposition due to hydrogen bond disruption at higher temperatures [11]. This was governed in a similar manner as leucine and isoleucine, since their larger branched side chains introduce steric hindrance and make flexible regions act as weak points, being more susceptible to thermal breakdown.

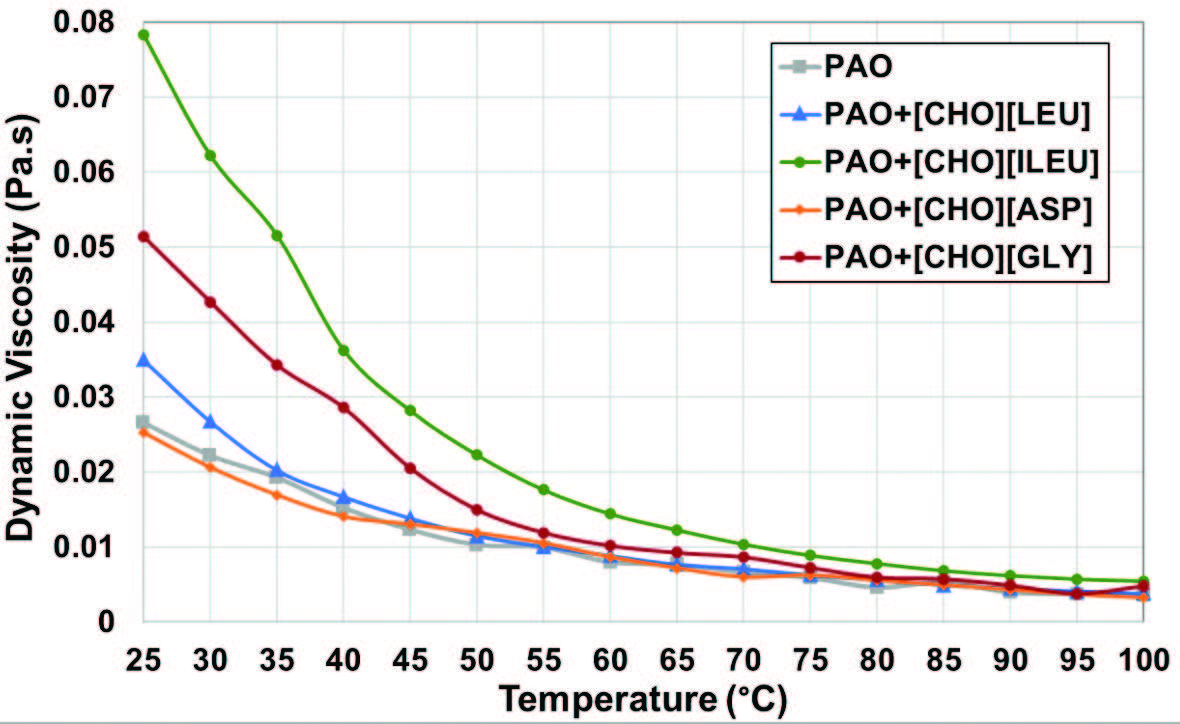

The dynamic viscosity of the base oil and the four different mixtures is shown in Figure 4. Based on the fluid curve behavior, all lubricants present a decreasing viscosity as temperature rises. The addition of additives, except [CHO][ASP], results in higher viscosity at lower temperatures. However, their effect diminishes at higher temperatures, leading to convergence of viscosity values. The mixture of PAO+[CHO][ILEU] has the highest viscosity over the whole temperature range, followed by PAO+[CHO][GLY].

Figure 4. Variation of the dynamic viscosity of the lubricants with temperature.

A strong intermolecular interaction of isoleucine’s side chain holds the molecules tightly, increasing the resistance of PAO+[CHO][ILEU] to flow [8]. On the other hand, PAO with [CHO][LEU] has a minor variation in viscosity. Glycine, with its flexible structure, may have interacted with PAO more uniformly with an entangled network and robust hydrogen-bonding, which provokes an increase in viscosity. PAO+[CHO][ASP] exhibited the lowest viscosity value compared to other mixtures, attributed to the polar and less bulky side chain of aspartic acid, which has weak intermolecular interaction with non-polar PAO [12]. Since the experiment runs under the boundary lubrication regime, there was minimal impact of the lubricant’s viscosity on their tribological performance. Nevertheless, the chemical structure of the lubricants still plays a central role in the lubricating properties [13].

2.2. Tribological Results

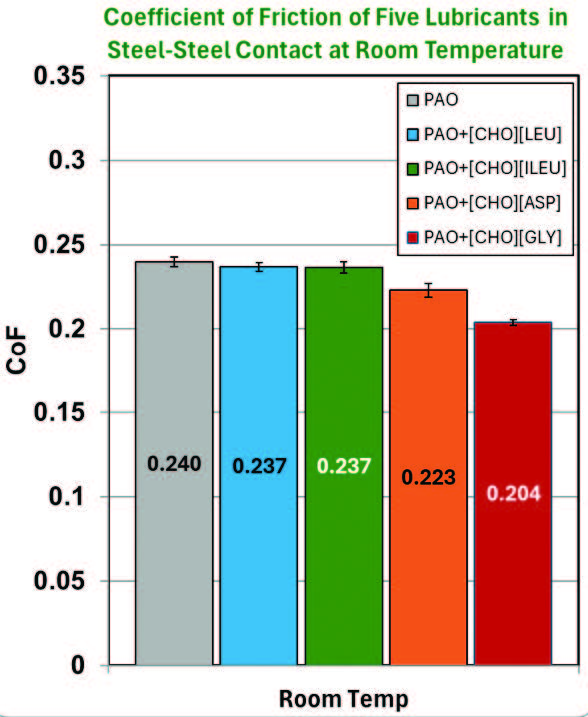

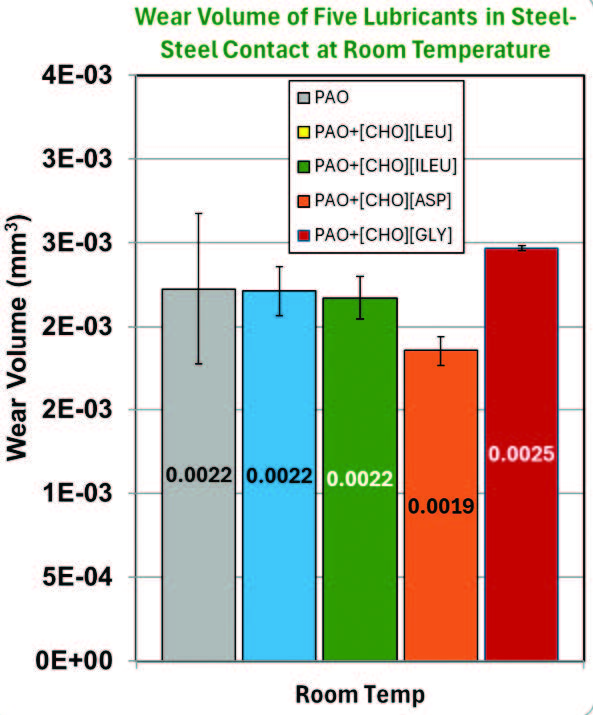

Coefficient of friction (CoF) and wear volume associated with each lubricant at room temperature conditions are displayed in Figure 5. PAO+[CHO][ASP] and PAO+[CHO][GLY] both showed 7.1% and 15.0% CoF reduction compared to neat PAO, respectively. However, both mixtures have opposite effects on wear volume, with PAO+[CHO][GLY] increasing wear by 13.6% and PAO+[CHO][ASP] decreasing wear by 13.6%. This suggests that both [CHO][ASP] and [CHO][GLY] can reduce shear at the interface; however, [CHO][GLY] does not provide sufficient surface protection against wear. The polar functional groups of [CHO][ASP] likely enhance their interaction with the surface, promoting the formation of a lubricious boundary film [14]. PAO+[CHO][LEU] and PAO+[CHO][ILEU] have not shown any significant variations in wear rate, as the error bars overlap.

Figure 5. Raw data of the average friction coefficient and wear volume at room temperature.

Figure 5. Raw data of the average friction coefficient and wear volume at room temperature.

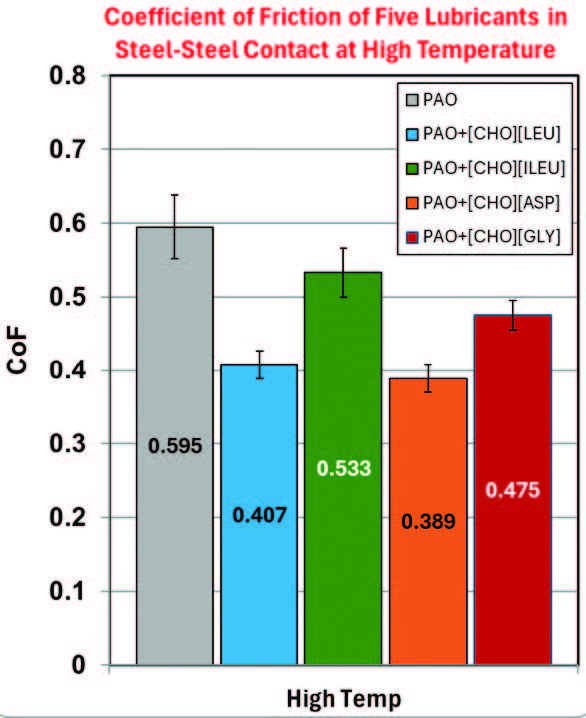

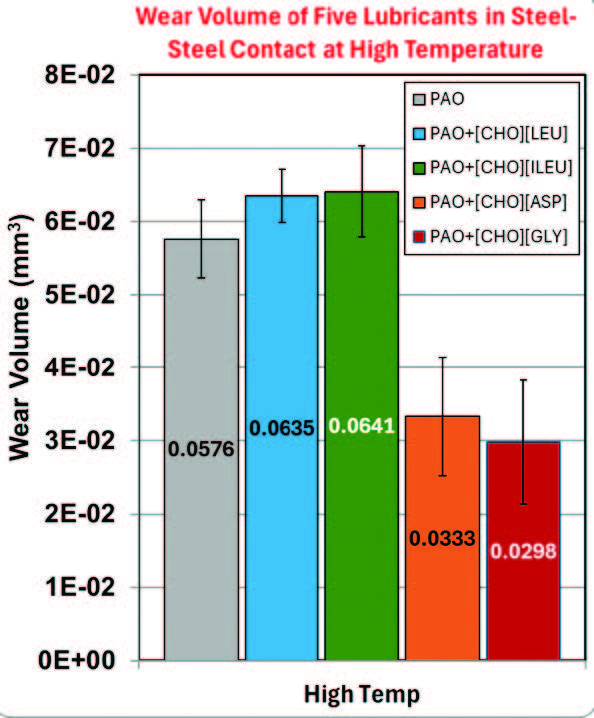

The tribological results are more pronounced at high temperature, as shown in Figure 6. Compared with room temperature conditions, steel-steel contacts at high temperatures inherently exhibit higher CoF and greater wear volumes because of reduced surface hardness and accelerated surface reactions. Adding 1 wt.% of the PILs to PAO did result in a significant reduction of the CoF, with PAO+[CHO][ASP] and PAO+[CHO][GLY] both showing 34.6% and 20.2% CoF reduction compared to neat PAO, respectively. Both mixtures also demonstrated a notable reduction in wear volume, indicating that high temperatures may activate possible tribofilm layers formation. PAO+[CHO][LEU] and PAO+[CHO][ILEU] have resulted in some reduction of CoF, yet no discernible variation in wear rate.

Figure 6. Raw data of the average friction coefficient and wear volume at high temperatures.

Figure 6. Raw data of the average friction coefficient and wear volume at high temperatures.

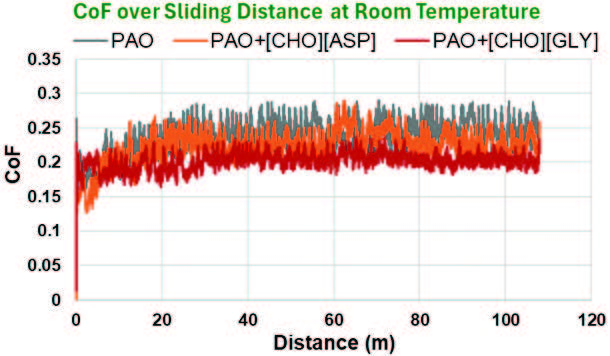

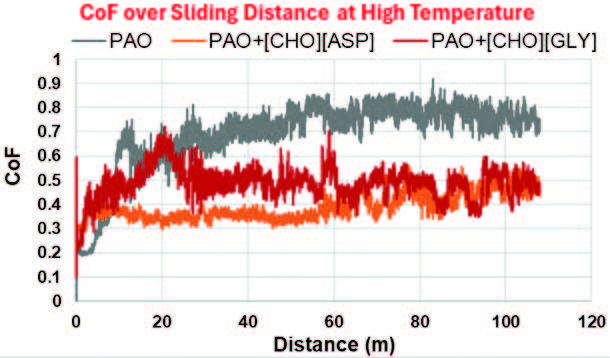

Figure 7 displays the CoF as a function of sliding distance for neat PAO and the two mixtures of interest (PAO+[CHO][ASP] and PAO+[CHO][GLY]). For the first few meters of sliding, the CoF was low but began to rise progressively. Eventually, the CoF plateaued and stabilized after 15 members and 30 meters of sliding under room temperature and high temperature conditions, respectively. The initial rise of the friction coefficient was due to initial surface conditioning. At the onset of sliding, the asperity interactions dominate as surface roughness is removed. This increases the area of contact, thus causing an increase in friction. The presence of additives, [CHO][ASP] and [CHO][GLY], resulted in a substantial decrease in friction over an extended distance after the initial rise. These behaviors were consistent with the CoF reduction observed in the previous Figures 5 and 6.

Figure 7. Variation of the friction coefficient over sliding distance at room and high temperatures.

Figure 7. Variation of the friction coefficient over sliding distance at room and high temperatures.

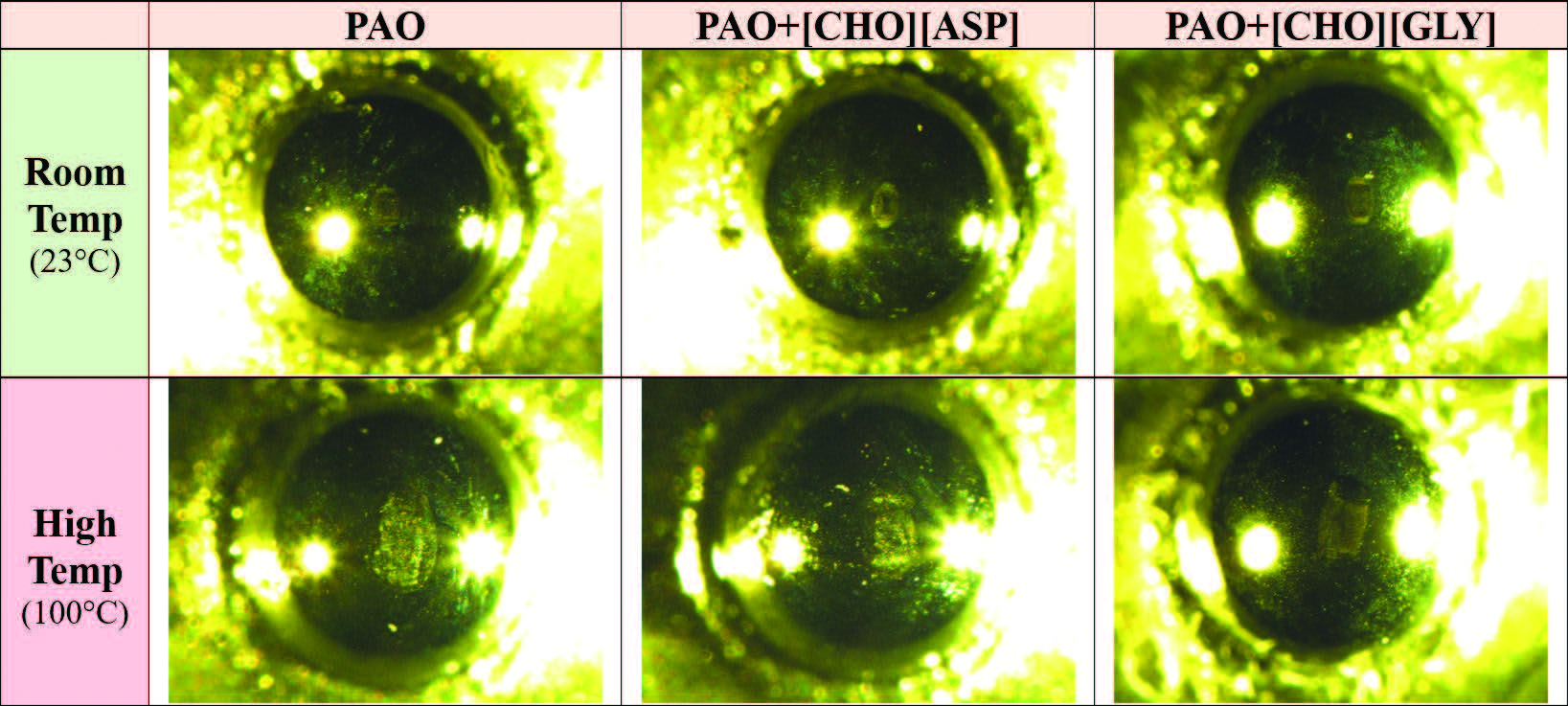

2.3. Wear Mechanisms

Optical images of the steel balls used in room and high temperature experiments for the neat PAO and the two mixtures (PAO+[CHO][ASP] and PAO+[CHO][GLY]) were presented in Figure 8. At room temperature, minor wear marks are detected at the contact point for all three balls, but the overall wear is considered negligible. When the temperature increased to 100°C, dominant evidence of adhesive wear was observed for all three balls. Adhesive wear is characterized by the transfer of steel from the disk to the surface of the ball at the point of contact. The ball lubricated with neat PAO displayed a larger worn area and greater material adhesion compared to the two mixtures, which suggests that neat PAO did not provide as much surface protection as PAO+[CHO][ASP] or PAO+[CHO][GLY]. These observations were consistent with the wear volume measurements, confirming that adding 1 wt.% of [CHO][ASP] or [CHO][GLY] to PAO results in lower material loss.

Figure 8. Optical images of the balls used for friction tests at room and high temperatures.

Figure 8. Optical images of the balls used for friction tests at room and high temperatures.

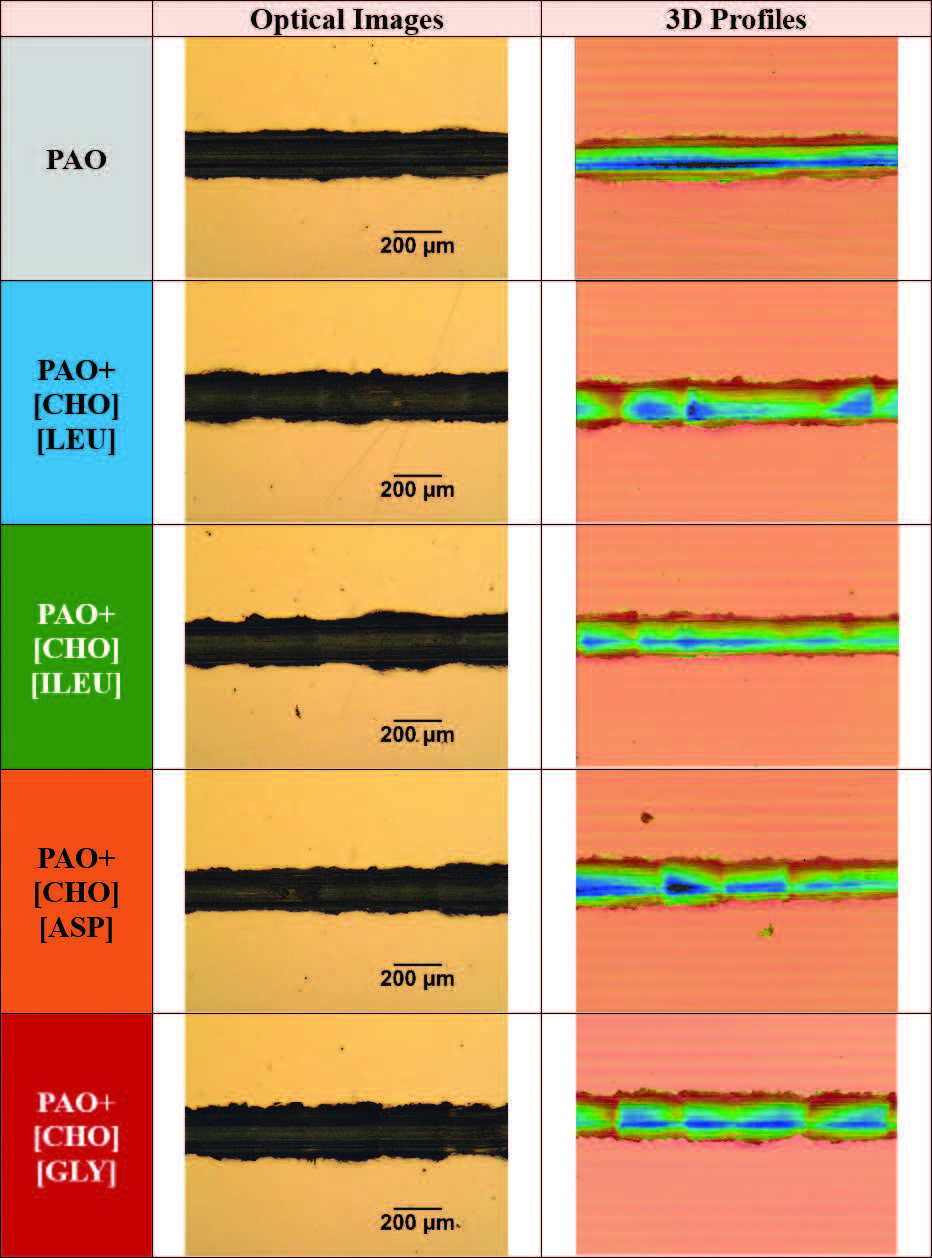

Optical images and 3D surface profiles of the wear tracks on steel surfaces under room temperature are captured in Figure 9. From the optical images, the track is visibly darkened and clearly distinguishable from the surrounding surface. The parallel grooves along the sliding direction indicate abrasive wear. This abrasive wear behavior may be attributed to wear debris trapped at the interface, functioning as a third body particles, which could cause the grooves. Ridges and material pile-up at the edges of the wear track signal plastic deformation. The 3D topographic profiles

(see Figure 9) provide a clear visualization of the worn surfaces, with color mapping highlighting variations in depth. At room temperature, the 3D surface profiles reveal no significant differences among the five wear tracks.

Figure 9. Optical image and 3D profiles of the resultant wear tracks on the steel disks after lubrication with respective lubricants and under room temperature.

Figure 9. Optical image and 3D profiles of the resultant wear tracks on the steel disks after lubrication with respective lubricants and under room temperature.

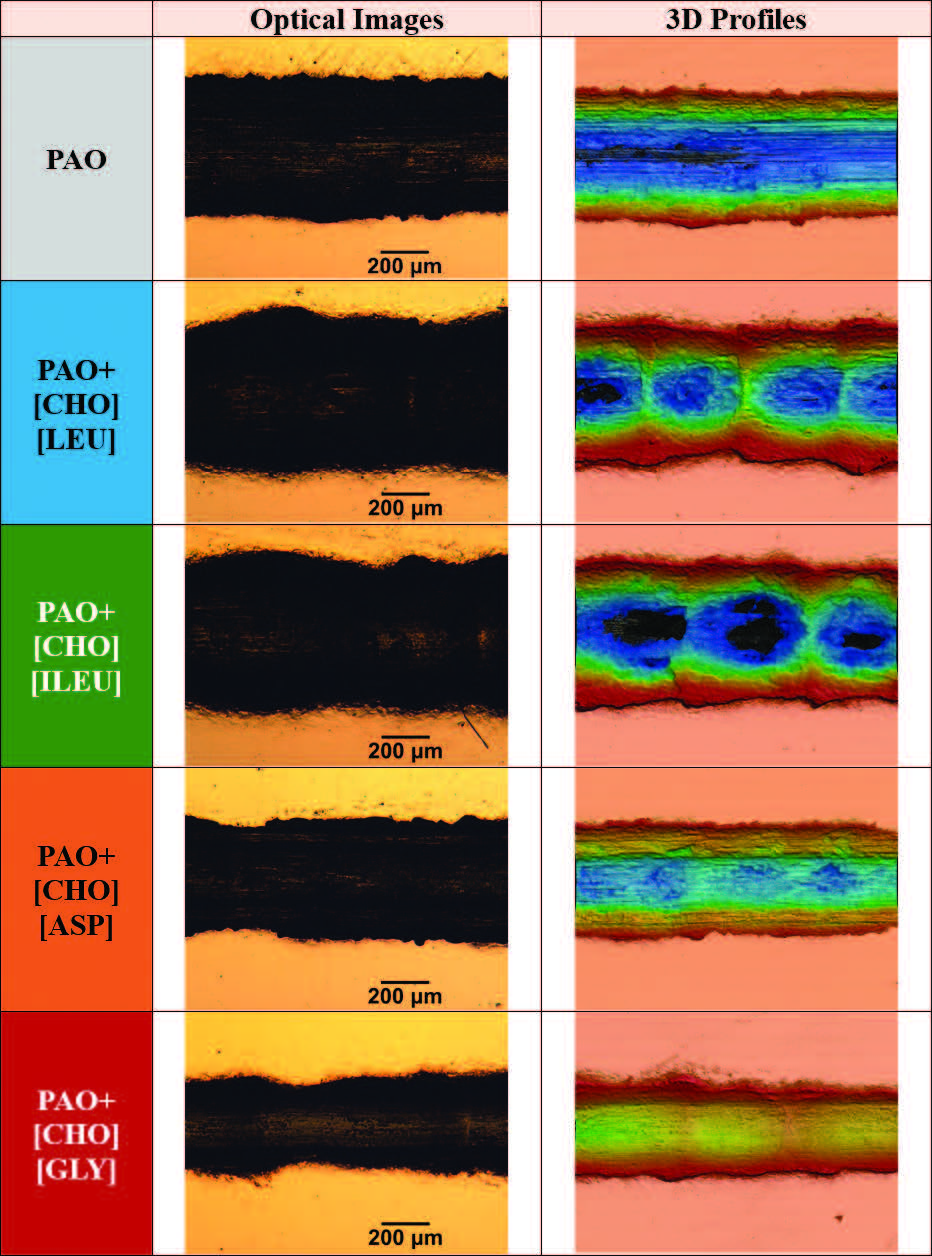

Optical images and 3D surface profiles of the wear tracks on steel surfaces subjected to high temperature testing are presented in Figure 10. A widened wear track with pronounced darkening is visible in optical images, suggesting severe surface interaction. Along with a strong abrasive component, adhesive wear with plastically deformed material along the track edges was the dominant mechanism for all wear tracks. Multiple dark patches can be spotted throughout the track, which are signs of micro-cracking. These wear mechanisms are common behavior in boundary lubrication [14].

Figure 10. Optical image and 3D profiles of the resultant wear tracks on the steel disks after lubrication with respective lubricants and under high temperature.

Figure 10. Optical image and 3D profiles of the resultant wear tracks on the steel disks after lubrication with respective lubricants and under high temperature.

The 3D topographic profiles of PAO+[CHO][ASP] and PAO+[CHO][GLY] in Figure 10 both exhibit a lower color intensity compared to other profiles. It represents a shallower wear track, implying that a better boundary film was effective in mitigating wear. On the other hand, PAO+[CHO][LEU] and PAO+[CHO][ILEU] exhibit periodic height variation and localized ridges throughout the track’s length, revealing irregular bump-like features. This suggests the stick-slip phenomena, reflecting the cyclic stick-slip motion of the contact interface. Such phenomena likely arise from unstable boundary film formation at elevated temperature conditions.

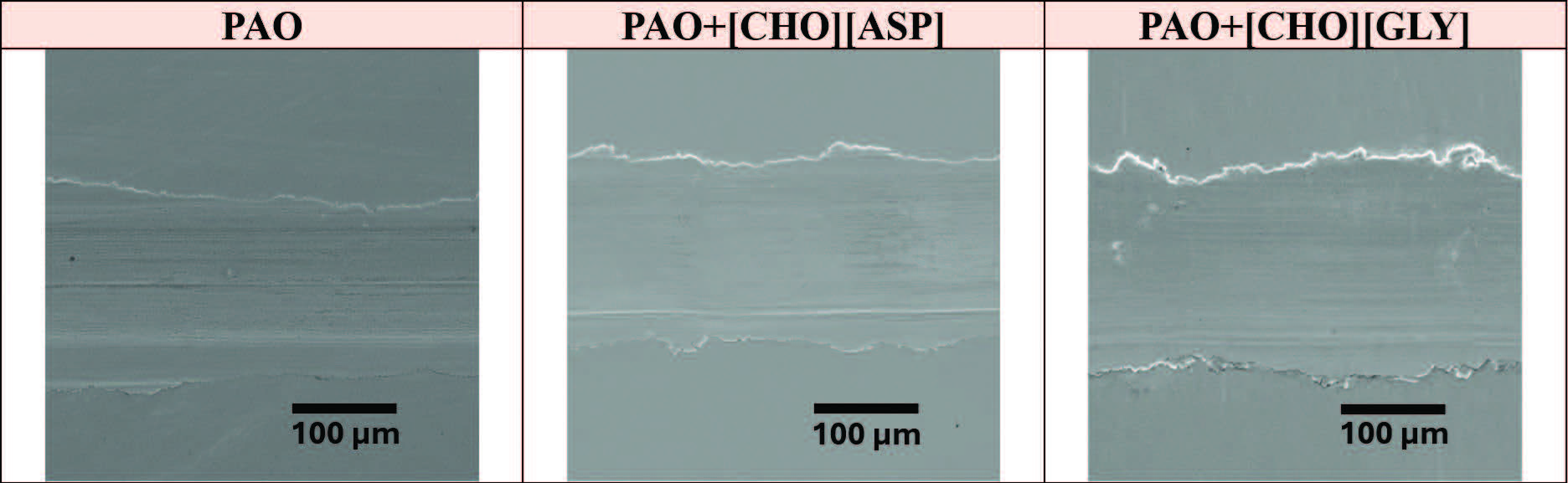

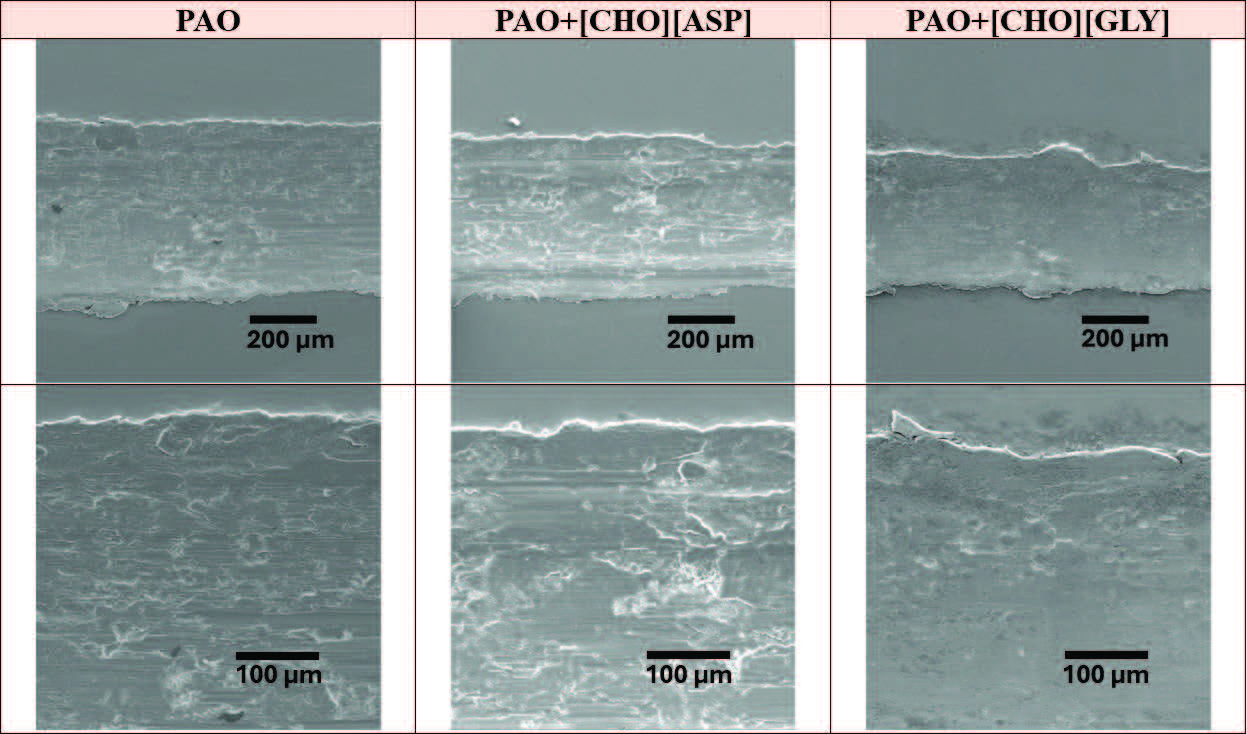

The close-up SEM micrographs provided a detailed view of the wear track morphology, revealing fine-scale features that were not easily observed in the optical images. SEM micrographs obtained at room temperature conditions show three wear tracks with shallow surface damage

(see Figure 11). All three wear tracks show no prolonged grooves or minimal cracking, indicating largely comparable wear behavior.

Figure 11. SEM micrographs of the resultant wear tracks on the steel disks after lubrication with respective lubricants and at room temperature.

Figure 11. SEM micrographs of the resultant wear tracks on the steel disks after lubrication with respective lubricants and at room temperature.

At high temperature conditions, the SEM micrographs

(see Figure 12) of the neat PAO-lubricated wear track show severe surface damage, with signs of irregular, discontinuous grooves. Wear track lubricated with PAO+[CHO][ASP] exhibits visible microcrack regions while crack density remains comparable to neat PAO, whereas PAO+[CHO][GLY] shows a smooth surface with fewer discernible features. These differences may indicate that PAO+[CHO][ASP] was associated with more evident surface fatigue interactions, while PAO+[CHO][GLY] provides improved surface protection.

Figure 12. SEM micrographs of the resultant wear tracks on the steel disks after lubrication with respective lubricants and under high temperature. Two images for each lubricant are shown: the overview of the wear track and the detailed view near the edges.

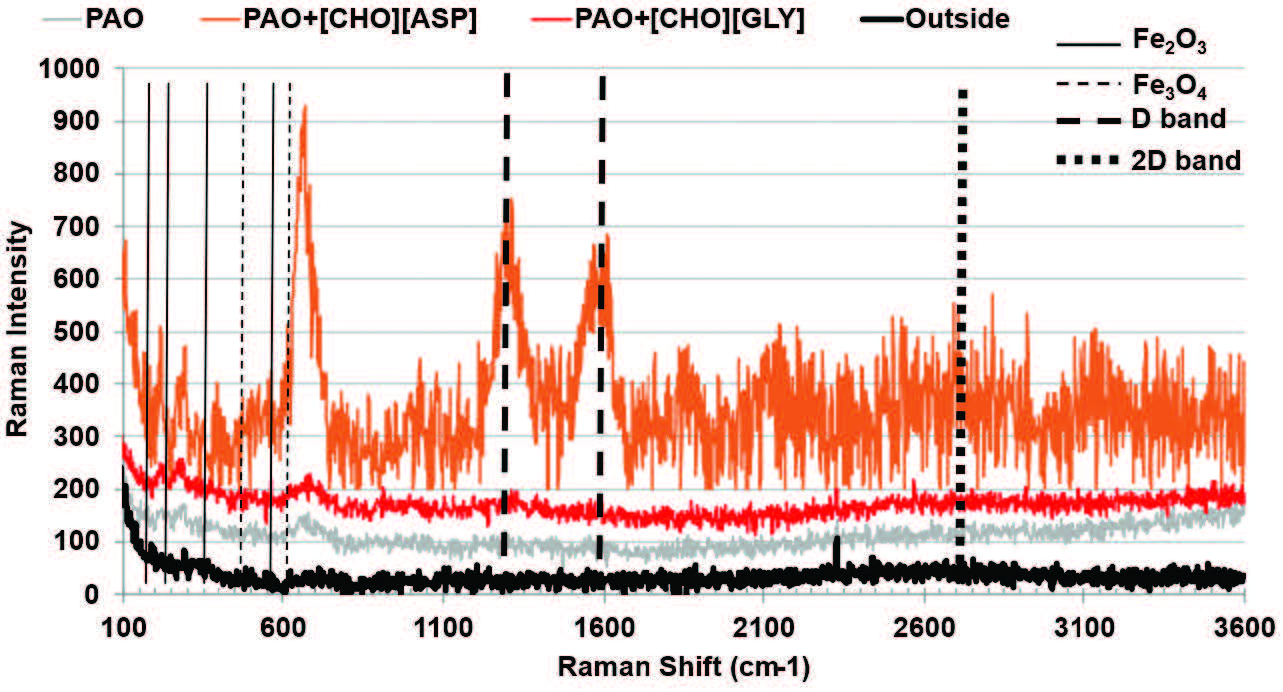

Raman spectra acquired from the wear tracks lubricated with neat PAO and PAO containing [CHO][ASP] or [CHO][GLY] reveal clear differences in tribochemical evolution at both room and elevated temperatures. Figure 13 shows the Raman spectra acquired from the steel surfaces lubricated with PAO, PAO+[CHO][ASP], PAO+[CHO][GLY], and a control spectrum acquired from the non-contact region (outside). Spectra collected from non-contact regions show only weak background signals, confirming that the features observed within the wear tracks originate from tribologically induced surface reactions.

Figure 13. Raman spectra acquired from the steel surfaces lubricated with PAO, PAO+[CHO][ASP], PAO+[CHO][GLY], and a control spectrum acquired from the non-contact region (outside) at room temperature.

Figure 13. Raman spectra acquired from the steel surfaces lubricated with PAO, PAO+[CHO][ASP], PAO+[CHO][GLY], and a control spectrum acquired from the non-contact region (outside) at room temperature.

At room temperature, the surface lubricated with PAO+[CHO][ASP] exhibits the most pronounced tribochemical signature, with intense iron-oxide bands (Fe2O3/Fe3O4 region) and a clear D-band response, indicating the formation of a chemically evolved tribolayer comprising an oxide-rich surface coupled with a carbonaceous (disordered carbon) component. This combination was consistent with a more protective boundary film. The oxide layer can stabilize the steel surface against adhesive junction growth [15], while the carbonaceous fraction can act as a low-shear interfacial layer [16]. In contrast, PAO+[CHO][GLY] shows comparatively weaker oxide/carbon signatures at room temperature, implying a less developed or less persistent tribofilm. This was consistent with its higher wear volume under room temperature testing, where tribochemical activation was limited.

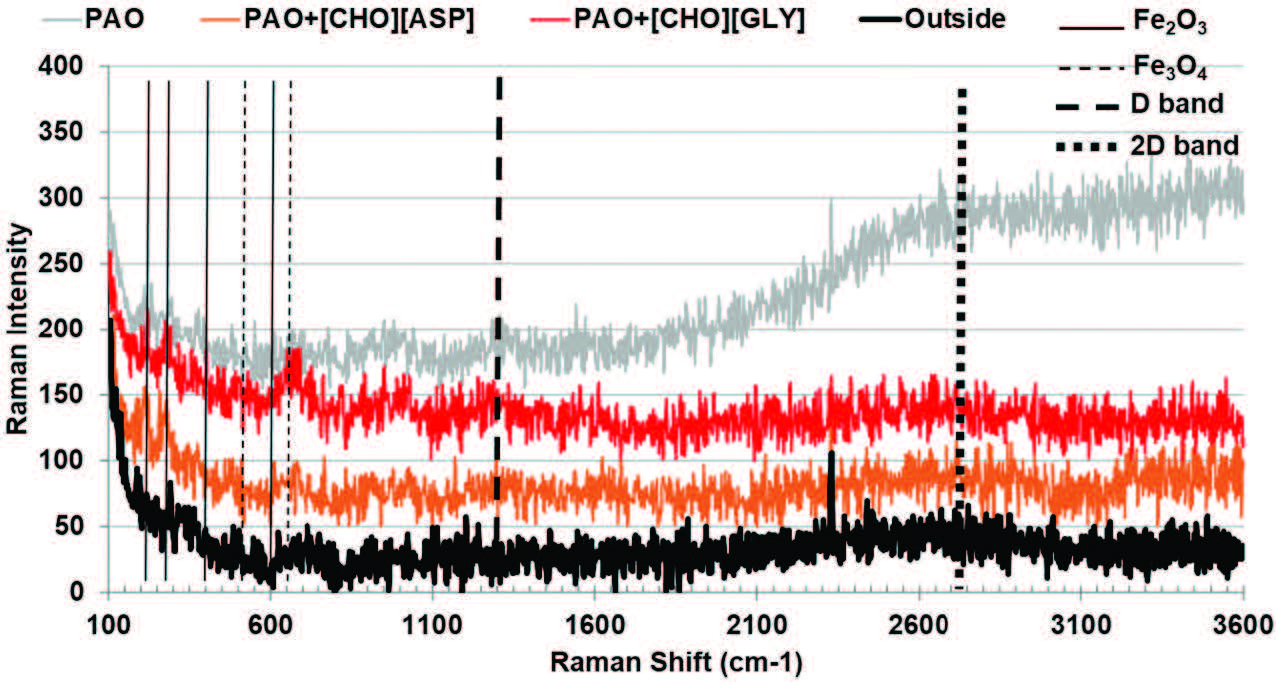

At elevated temperature, as shown in Figure 14, both PAO+[CHO][ASP] and PAO+[CHO][GLY] yield wear-track spectra indicative of tribofilm formation sufficient for good antiwear behavior, consistent with their improved wear performance in this regime. Importantly, the high temperature spectrum for neat PAO displays a markedly higher Raman intensity, which likely reflects substantial thermal/tribochemical degradation (e.g., accumulation of oxidized organics and/or thick heterogeneous layers) rather than a stable protective boundary film [17, 18]. In other words, high Raman intensity for neat PAO was better interpreted as evidence of severe surface chemistry and deposit build-up, not necessarily beneficial protection. By comparison, the PIL-containing formulations appear to promote a more controlled tribochemical response, supporting the formation of protective films under thermal activation, thereby limiting material loss.

Figure 14. Raman spectra acquired from the steel surfaces lubricated with PAO, PAO+[CHO][ASP], PAO+[CHO][GLY], and a control spectrum acquired from the non-contact region (outside) at high temperature.

These results suggest that [CHO][ASP] was more effective at room temperature because it promotes rapid formation of an oxide- and carbon-assisted tribolayer, whereas [CHO][GLY] requires higher temperature to activate comparable protective tribochemistry. At high temperature, both additives were effective, while neat PAO undergoes extensive degradation that does not translate into comparable wear protection.

3. Conclusion

This study investigated the tribological behavior of choline amino acid PILs used as 1 wt.% additives in a low-viscosity, non-polar PAO under steel-steel contact at both room and high temperatures. The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

1. PAO+[CHO][ASP] tribologically performed better than the other three PILs evaluated, as evidenced by a decrease in friction coefficient and wear volume. PAO+[CHO][GLY] performs effectively at high temperature, attributed to protective tribofilm activation under elevated thermal conditions.

2. The chemical structures of the PIL additives modify the base oil, altering its thermal stability and flow characteristics.

3. Wear analysis revealed adhesive wear with plastic deformation for all wear tracks. At high temperature, PAO+[CHO][ASP] and PAO+[CHO][GLY] produced shallower and narrower wear tracks, while PAO+[CHO][LEU] and PAO+[CHO][ILEU] produced non-uniform wear tracks.

4. Ramen spectroscopy indicated high amounts of iron oxides and carbonaceous species within the wear track for PAO+[CHO][ASP]. At elevated temperature, the wear track formed with PAO+[CHO][GLY] shows a high amount too.

5. The choline amino acid PILs, particularly PAO+[CHO][ASP] and PAO+[CHO][GLY], can be useful additives for enhancing non-polar base oils’ lubricating properties in steel-steel contact applications.

Acknowledgement

Esmond Lau would like to thank STLE for the support provided by the E. Richard Booser Scholarship. The authors acknowledge the National Science Foundation under Award No. 2246864 for supporting this research. We thank Dr. Michael Coleman and Dr. Filippo Mangolini for their contributions to this research.

REFERENCES

1.

S. Waheed et al., “Ionic liquids as lubricants: An overview of recent developments,”

J. Mol. Struct., vol. 1301, p. 137307, Apr. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.137307.

2.

M. Cai, Q. Yu, W. Liu, and F. Zhou, “Ionic liquid lubricants: when chemistry meets tribology,”

Chem. Soc. Rev., vol. 49, no. 21, pp. 7753–7818, Nov. 2020, doi: 10.1039/D0CS00126K.

3.

M. D. Avilés, F. J. Carrión, J. Sanes, and M. D. Bermúdez, “Effects of protic ionic liquid crystal additives on the water-lubricated sliding wear and friction of sapphire against stainless steel,”

Wear, vol. 408–409, pp. 56–64, Aug. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.wear.2018.04.015.

4.

H. Guo, T. W. Smith, and P. Iglesias, “The study of hexanoate-based protic ionic liquids used as lubricants in steel-steel contact,”

J. Mol. Liq., vol. 299, p. 112208, Feb. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112208.

5.

Y. Li et al., “Choline amino acid ionic Liquids: A novel green potential lubricant,”

J. Mol. Liq., vol. 360, p. 119539, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119539.

6.

D. K. Kiboi et al., “Physicochemical and lubricating properties of choline amino acid ionic liquids as neat lubricants for steel-steel contact,”

Wear, vol. 578–579, p. 206198, Sept. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.wear.2025.206198.

7.

J. Qu and J. J. Truhan, “An efficient method for accurately determining wear volumes of sliders with non-flat wear scars and compound curvatures,”

Wear, vol. 261, no. 7, pp. 848–855, Oct. 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.wear.2006.01.009.

8.

M. Moosavi, N. Banazadeh, and M. Torkzadeh, “Structure and Dynamics in Amino Acid Choline-Based Ionic Liquids: A Combined QTAIM, NCI, DFT, and Molecular Dynamics Study,”

J. Phys. Chem. B, vol. 123, no. 18, pp. 4070–4084, May 2019, doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b01799.

9.

A. Le Donne and E. Bodo, “Cholinium amino acid-based ionic liquids,”

Biophys. Rev., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 147–160, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s12551-021-00782-0.

10.

C. Herrera, G. García, M. Atilhan, and S. Aparicio, “A molecular dynamics study on aminoacid-based ionic liquids,”

J. Mol. Liq., vol. 213, pp. 201–212, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2015.10.056.

11.

Y. Cao and T. Mu, “Comprehensive Investigation on the Thermal Stability of 66 Ionic Liquids by Thermogravimetric Analysis,”

Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 53, no. 20, pp. 8651–8664, May 2014, doi: 10.1021/ie5009597.

12.

T. Kimura, N. Matubayasi, and M. Nakahara, “Side-Chain Conformational Thermodynamics of Aspartic Acid Residue in the Peptides and Achatin-I in Aqueous Solution,”

Biophys. J., vol. 86, no. 2, pp. 1124–1137, Feb. 2004, doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74187-9.

13.

E. Nyberg, C. Y. Respatiningsih, and I. Minami, “Molecular design of advanced lubricant base fluids: hydrocarbon-mimicking ionic liquids,”

RSC Adv., vol. 7, no. 11, pp. 6364–6373, Jan. 2017, doi: 10.1039/C6RA27065D.

14.

M. K. A. Ali, M. A. A. Abdelkareem, K. Chowdary, M. F. Ezzat, A. Kotia, and H. Jiang, “A review of recent advances of ionic liquids as lubricants for tribological and thermal applications,”

Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol., vol. 237, no. 1, pp. 3–26, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1177/13506501221091133.

15.

M. Hanesch, “Raman spectroscopy of iron oxides and (oxy)hydroxides at low laser power and possible applications in environmental magnetic studies,”

Geophys. J. Int., vol. 177, no. 3, pp. 941–948, June 2009, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04122.x.

16.

A. Shirani, Y. Li, O. L. Eryilmaz, and D. Berman, “Tribocatalytically-activated formation of protective friction and wear reducing carbon coatings from alkane environment,”

Sci. Rep., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 20643, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00044-9.

17.

M. Homayoonfard, S. L. M. Schroeder, P. Dowding, O. Delamore, and A. Morina, “Frictional Behavior and Tribofilm Formation of Organic Friction Modifiers under Severe Reciprocating Conditions,”

Langmuir, vol. 41, no. 44, pp. 29616–29626, Nov. 2025, doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5c03784.

18.

W. Song et al., “In-situ catalysis of green lubricants into graphitic carbon by iron single atoms to reduce friction and wear,”

Nat. Commun., vol. 16, no. 1, p. 2919, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-58292-6.