KEY CONCEPTS

•

Full-chain esterization of metalworking fluids and critical machine oils can turn tramp oil ingress from a chronic liability into a more predictable and manageable variable.

•

The initial cost of system conversion and higher fluid purchase prices can be mitigated by documented cost savings over the long run.

•

The suitability of end-to-end compatible fluids for a specific system depends on overall performance and fluid life, supply chain reliability, performance criticality and cost factors.

Conventional wisdom holds that tramp oil contamination of metalworking fluids (MWFs) is generally detrimental. Hydraulic oils and lubricants leaking from slideways and spindles often degrade the MWF’s performance by changing its viscosity and lubricity, splitting MWF emulsions and creating conditions that favor microbial growth. However, several industrial operations, including some high-end passenger vehicle manufacturers in Europe, currently use water-miscible MWFs that operate compatibly with ester-based machine lubricants and hydraulic oils while rejecting hydrocarbon oil contaminants.

1

“Conventional methodologies deal with tramp oil reactively,” says STLE member Shahin Jamali, president and lead formulator at Synix Solutions Inc. “Skimmers, coalescers and filters remove tramp oil only after it has entered the MWF. Yet in real operations, a portion of that oil becomes temporarily—and undesirably—emulsified under shear, pressure, flow and temperature, making complete capture difficult. If leakage is unavoidable and full separation unattainable, why not design the system to work with it?”

Some MWF formulations currently on the market feature an emulsifier system that is tuned for specific base oils (notably esters). These formulations can tolerate—and in some cases, even make use of—a limited ingress of chemically compatible lubricants. These formulations reject incompatible contaminant oils, which can be skimmed from the surface and disposed of. In practice, some large European manufacturing operations use straight-oil and water-dilutable MWFs engineered to maintain compatibility with specified machine and hydraulic lubricants while rejecting mineral (hydrocarbon) tramp oils

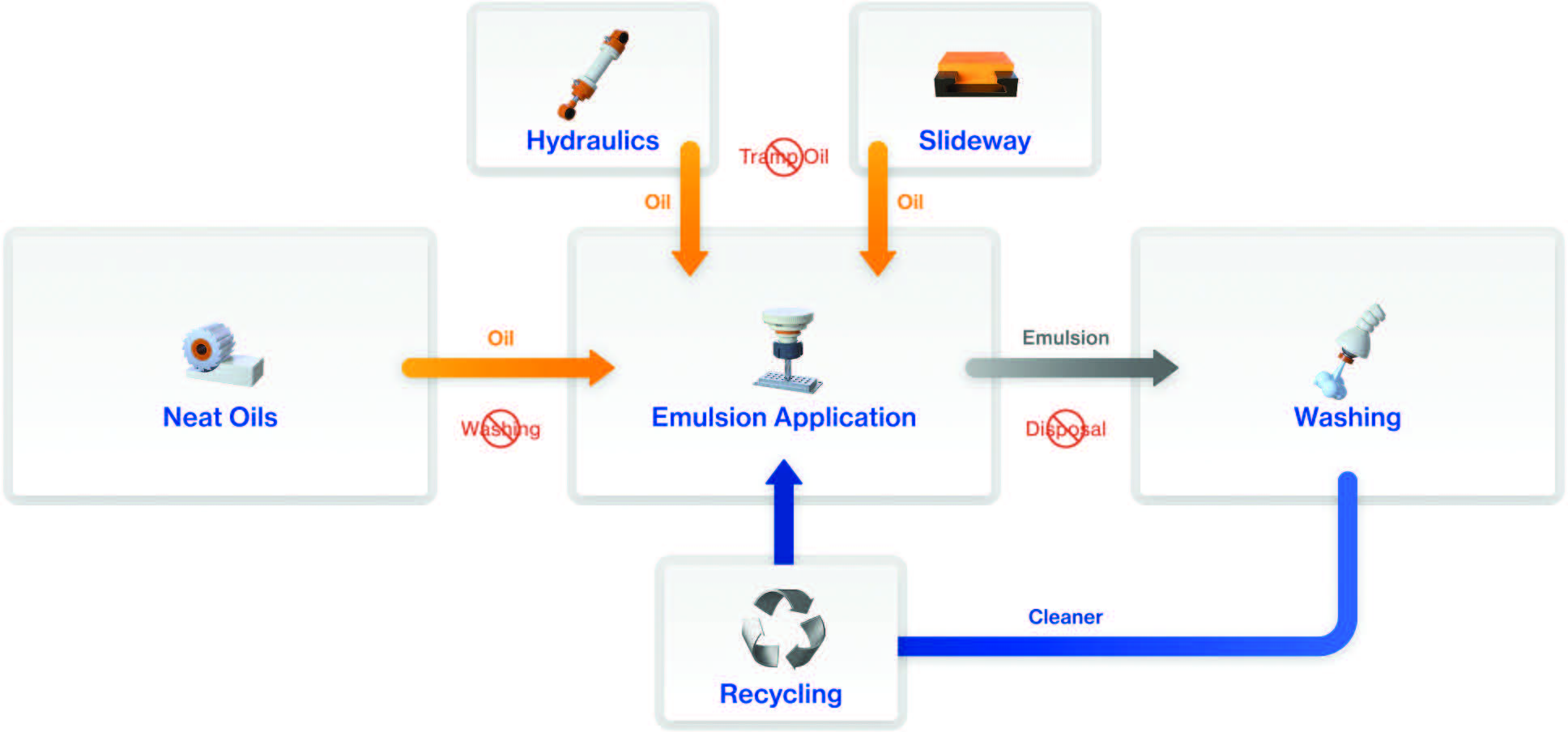

(see Figure 1).

Figure 1. In compatible lubricant systems, an ester emulsion-type MWF tolerates limited ingress of hydraulic and machine lubricant oil, while rejecting mineral-based oils. Compatible cleaners wash the MWF from the workpiece and recycle it back to the MWF flow. Figure courtesy of Oemeta.

For example, one company introduced a two-component MWF product line to the market in the 1990s, in which an additive package is mixed with a straight or water-dilutable 72% ester base fluid at the ratio best suited to a specific metalworking application. The MWF products are formulated for compatibility with the ester-based machine and hydraulic lubricant products. These products are used by some German auto manufacturers, as well as customers in the aerospace and medical component industries.

2,3

Instead of viewing tramp oil solely as a contaminant, Jamali says, the question becomes: Can tramp oil function as a designed component of the fluid system by building an MWF that preferentially emulsifies small amounts of ester-based lubricants while rejecting other base stocks? As ester-based slideway and hydraulic oils, along with ester-centric MWF emulsions, see wider adoption, he says, this proactive approach becomes increasingly feasible.

Tramp oil problems

Tramp oil contamination in conventional MWFs cuts coolant life, resulting in more frequent MWF changeouts, higher waste-fluid volumes, shortened tool life, poorer surface finish, degraded dimensional consistency and reduced first-pass yield. These factors, in turn, drive up operating costs and require extra labor and energy to run separation equipment.

In the sump, leaked oils form surface films that impede oxygen transfer and favor anaerobic microbes including sulfate-reducing bacteria. Microbial contamination can produce a “rotten egg” hydrogen sulfide odor, pH drift and corrosion risk. These tramp oils also compete for the MWF’s emulsifiers, leading to creaming or splitting, unstable droplet size distributions and sticky residues.

Demulsifiers in some hydraulic, way or gear oils can counteract emulsifiers in the MWF package. Emulsified tramp oil can raise apparent viscosity, impede heat removal and flushing and undermine concentration control. Once tramp oil is emulsified into the MWF, skimmers can remove MWF along with contamination. When this happens, it may be necessary to use coalescers or centrifuges, which increases capital, maintenance and energy costs.4 Because reactionary control is done after contamination occurs and is least effective after shearing, temperature and other factors have caused a temporary emulsification of the tramp oil, Jamali says, plants often end up in a loop of partial contaminant removal and gradual MWF degradation.

STLE member Jennifer Lunn, product manager – metal forming lubricants and mill applied corrosion preventives at Fuchs Lubricants Co., explains that tramp oil contamination can be dealt with in a variety of ways. Fully synthetic MWFs are best at rejecting tramp oil, she says. Because they are often true solutions, made up of fully water-soluble components, they do not always use the emulsifiers that can pull tramp oil into an emulsion. This makes fully synthetic MWFs incompatible with mineral oils. Thus, they naturally reject mineral-based tramp oils, which can be skimmed off easily.

Tramp oil is also not as much of an issue with straight-oil MWFs, Lunn adds. Tramp oils that enter the MWF stream can change the viscosity of straight-oil MWFs and add small amounts of other additive chemistries. However, these straight-oil MWFs are typically not recirculated in the same manner as for water-miscible systems, and so the contaminated oil does not re-enter the lubricant stream after being flushed away. Thus, the continuous replenishment of the MWF stream with fresh oil limits the amount of damage that tramp oil can do.

Soluble oil MWFs, Lunn says, are often made using naphthenic oils, while hydraulic fluids are made from paraffinic oils. The difference in the hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) of the two types of oils requires different emulsifier combinations, which indirectly improves tramp oil rejection.

Lunn also notes that it is important in any of these systems to skim off the tramp oil and not allow it to float on the top of the emulsion. Because a tramp oil layer significantly reduces oxygen permeation in the in-use MWF, it can promote the growth of anaerobic microbes. “I’ve seen sumps with an inch or two of tramp oil, and if it’s allowed to sit for any length of time, say over a weekend, bacterial growth can produce unpleasant odors and instability of the emulsion upon startup on Monday morning,” she says.

Emulsion-type MWFs, Lunn says, can experience tramp oil problems when they are recirculated and tramp oil is emulsified into the MWF. Hydraulic oil contamination effectively dilutes the concentration of important additive components of the formulation such as corrosion inhibitors, emulsifiers, extreme pressure additives, boundary lubricity additives and microbicides in the MWF. Some hydraulic oils contain demulsifiers that prevent water from contaminating the oil, and these can counteract or destabilize the emulsifiers in the MWF.

“Some oil soluble additives in MWFs can be extracted into tramp oil, which reduces their concentrations in the water-diluted MWFs, resulting in loss of performance,” says STLE member Patrick Brutto, technical application specialist at Faith-Full MWF Consulting. “Examples of additives which can be removed by extraction into hydrocarbon-based tramp oils are dicyclohexylamine (DCHA) and o-phenylphenol (OPP).” He concurs with Lunn that solution synthetic MWFs are best at rejecting tramp oil. Because they contain water-soluble components and usually do not contain emulsifiers, solution synthetic MWFs are often incompatible with mineral oils, he adds.

Tramp oil contamination also skews refractometer measurements used to measure fluid concentration. “Concentration is the number one factor to ensure a MWF is being used efficiently and effectively,” Lunn explains. Because refractometers do not distinguish between hydraulic oils and MWFs, the reading can be misleading, leading operators to believe that they are within the correct operating concentration range for the MWF. If the MWF additive concentration drops too low, the result could be corroded metal surfaces, microbial contamination and emulsion splitting. On the other hand, she adds, operating at a higher concentration of make-up fluid in the hopes of counteracting dilution by tramp oils can drive up operating costs and cause workers to develop skin irritations and respiratory problems.

In addition to affecting the performance of the MWF, Lunn says, tramp oil contamination can cause waste disposal problems. Hydraulic fluids containing zinc-based additives, for example, can cause contaminated MWFs to exceed locally mandated limits for zinc in wastewater, resulting in additional waste treatment expenses.

Compatibility by design is a better approach, says Jamali. “Build the system so that small amounts of

compatible fluid ingress don’t destabilize the emulsion—and can even contribute to boundary lubrication without destabilizing the emulsion—while

incompatible oils are rejected and skimmed.” Full-chain fluid compatibility programs involve not only the metalworking coolant but also the slideway, hydraulic and spindle oils. Operations using this approach, he says, report longer sump life with fewer cleanouts, better tool life and finish from steadier lubrication and cooling, cleaner machines and parts, lower disposal and energy use, and simpler upkeep because routine top-offs don’t upset the fluid. In short, he says, “Stop fighting every drop—engineer the chemistry so the right ingress becomes part of the plan.”

Formulation challenges

Esters are commonly used as part of the base-oil phase in water-dilutable MWFs, Jamali notes. In practice, formulators frequently include synthetic esters (e.g., polyol esters) to tune polarity, lubricity, cleanliness and stability. Because ester chemistry is modular and highly designable, he says, ester performance properties can be tailored through the choice of the acids and alcohols used to form the esters. Historically, esters carried a price premium, he adds, so they were applied at optimized treat rates to balance performance and cost. Today, pricing is generally more favorable, depending on the application. While biobased (plant-derived) esters are sometimes perceived as pricier, he says, this is no longer universally true. Esters can be cost-competitive with other base stocks, depending on applications and market conditions.

A challenge for end-to-end compatible fluid systems, says STLE member John Fitzsimmons, technical sales associate with S&S Chemical Co., Inc., is coming up with machine lubricant and MWF formulations that do not have incompatible additives that form insoluble salts or cause a lubricant to fail when various fluids mix. He notes that it is possible to formulate compatible machine lubricant oils and MWFs for some applications.

The challenge, Fitzsimmons says, is accommodating those differences in the performance requirements of the different processes. Does the application use a water-dilutable MWF product, while the machine lubricant uses a neat oil? What happens when tramp oil leaks into the MWF coolant system and changes the MWF’s concentration? Can the MWF maintain the properties needed to maintain the quality of the finished parts? How much machine oil volume can the MWF accommodate and still function adequately?

Machine lubricants, hydraulic oils and MWFs each carry their own additive packages. Additive carryover from tramp oil is typically small relative to the volume of MWF and usually has limited impact, Jamali says. However, he adds, demulsifiers in some machine oils can interfere with MWF emulsifiers and should be addressed explicitly in any compatibility program by specifying non-interfering machine oil packages.

Formulating a water-dilutable MWF that tolerates—or even benefits from—small amounts of machine oil leakage requires anticipating what the MWF will encounter. “Achieving stable integration requires sophisticated formulation of both the machine oils and the water-dilutable MWF concentrate,” says Jamali. “This means tailoring the surfactant/emulsifier system to prevent emulsion splitting, phase drift or phase inversion, or adverse interactions with performance additives (e.g., extreme pressure and antiwear agents or corrosion inhibitors) when oils inevitably mix under shear and load.”

A well-designed MWF minimizes the impact of carryover on lubricity, heat removal and emulsion stability. This minimization is essential for maintaining long-term emulsion tightness, predictable and controlled droplet size distribution, and resistance to shear- and heat-induced destabilization. “The challenge,” Jamali says, “is creating cross-compatibility among oil types and base stocks with distinct additive chemistries, while preserving the MWF’s intended performance window.”

Developing full-chain esterization programs, Jamali says, requires formulators to verify the fluids’ sensitivity to water hardness, alkalinity and potential hydrolytic stress, as well as selecting additives that are stable in ester-rich systems. Formulators also evaluate the hydrolytic and oxidative stability of the chosen esters under sump conditions. All ester slideway, hydraulic and spindle oils must be compatible with the seals, paints and elastomers with which they come into contact. Biostability controls, including alkalinity maintenance and biocide strategies, extend fluid life by retarding microbial growth. Some programs, he says, also use two-component dosing—separate packages for lubrication/power oils and for additives—to maintain lubricity and corrosion control without concentration creep.

Despite these challenges, Jamali says, operations already using integrated, compatibility-driven strategies report benefits that include downsizing or eliminating tramp oil separation hardware, significantly extending MWF service life under controlled monitoring, lowering fluid waste and disposal costs and reducing energy consumption. In addition, compatible cleaners in some systems can be recycled back into the emulsion, simplifying maintenance, Jamali says. Large, centralized systems and high-output machining centers are especially strong candidates for this approach, he adds.

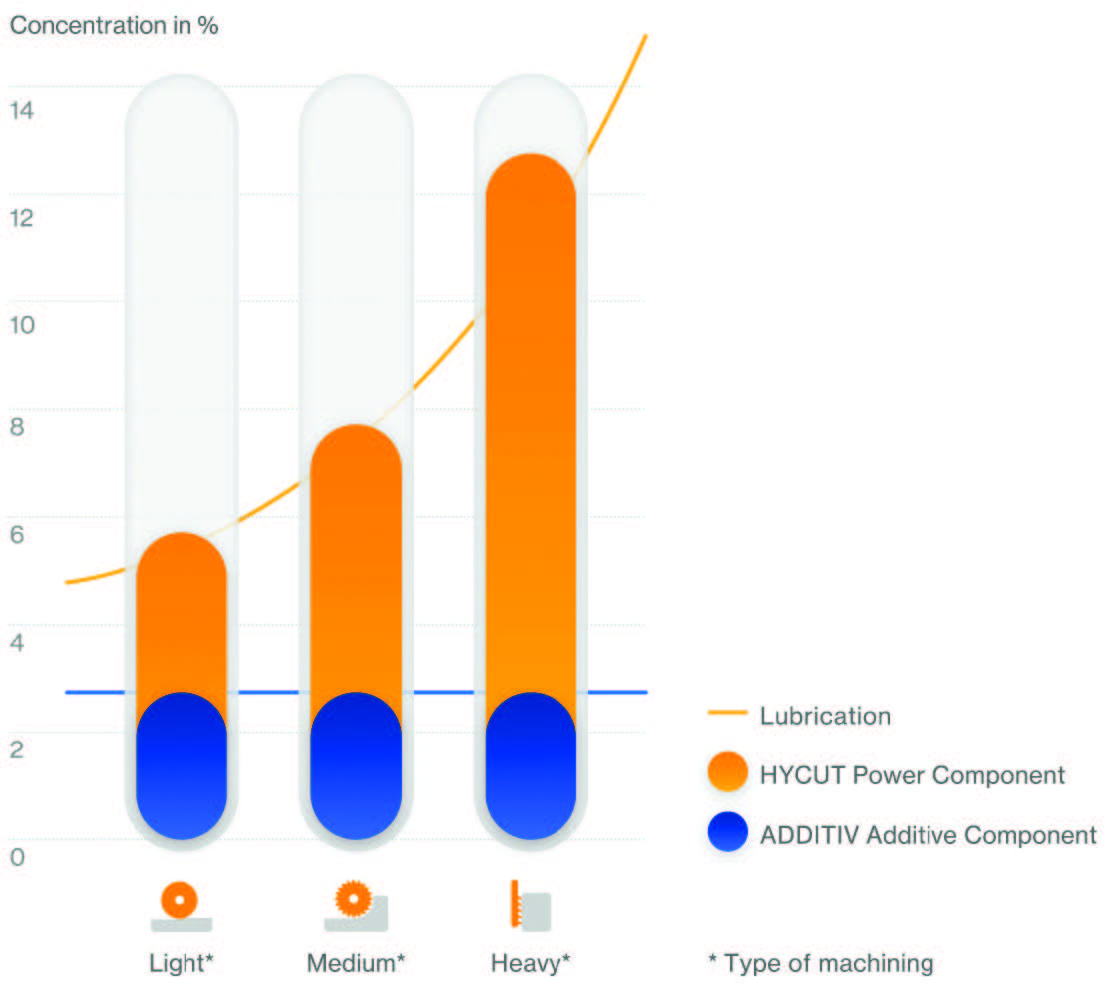

Tramp oil-compatible MWFs on the market support a wide range of processes, Jamali says, including drilling and deep-hole drilling, turning, milling, tapping, honing, broaching, reaming, grinding and forming. The base-oil-to-additive ratio is adjusted to maintain the required performance levels and lubricity balance for a given application

(see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Two-component lubricant systems use a standard additive package (blue) and vary the amount of base oil (orange) depending on the type of application. Figure courtesy of Oemeta.

Synthetic ester oils used for an end-to-end product line can be used as straight oils for applications including hydraulics and grinding, or they can be emulsified with water for use in other metalworking applications, says Matthew Dallons, CEO of Oemeta North America. For example, compatible hydraulic oil that leaks into a grinding system contributes to the grinding oil stream. When the parts are washed off using a compatible cleaner, the entire mixture is recycled into the MWF stream. A single additive package, designed for such end-to-end systems, can be used for all the fluids, and the oil-to-additive ratio is adjusted for the type of application.

Dallons explains that a high-grade ester oil can be adapted to serve a range of applications, with viscosities ranging from ISO VG 6 to ISO VG 220. Of course, mixing various oil streams requires monitoring to maintain the proper oil-water-additive balance for the application. Refractometer readings can be misleading because they do not distinguish the source of the oil or the additive concentrations. However, he says, test strips are a convenient way of monitoring pH, water hardness and additive concentrations to make sure that the MWF emulsion remains stable and stays within the effective performance window.

Chemical buffers can be added to the MWF to control the effects of specialized additives like tackifiers for way lubes and extreme pressure additives for hydraulics, especially for use in working with light metals such as aluminum. The additive packages for these lubricants can include biocides or not, as the customer requires, Dallons says, adding that even the biocide-free packages are formulated to retard microbial growth.

Making the transition

Would using the same base oil for hydraulics, machine lubricants and MWFs, along with compatible additive packages, solve the tramp oil problem? “In an ideal world, yes,” Lunn says. However, “You’ve got to take into account the different requirements of each fluid. On the MWF side you’ve got tool life, part complexity and substrate, feeds and speeds and cleanliness to consider. On the machine lubes, you’re bound by specifications as dictated by the machine manufacturers.”

“I’m sure it’s possible to have one oil for all these things, but it’s not going to be the best at everything,” Lunn continues. “You’re going to have to compromise some performance so you can have the ease and lower complexity of using one product.” She adds that this might be feasible using straight oils, but products using PAOs and plant-based oils come with a cost increase over traditional mineral oils and would likely be too expensive to justify converting most the existing systems. Customers are generally driven by regulatory requirements or significant performance improvements to justify switching over, she says.

Lunn notes that compatible fluid systems would probably work best if these fluids were used end-to-end rather than adopting them for one application (e.g., either hydraulics or MWFs) and using conventional fluids in the other applications. However, she says, the one-fluid approach could be a difficult sell because, with proper fluid monitoring, well maintained hydraulic, gear or slideway oils can have very long lifetimes. In contrast, water-based fluids have a finite life and must be dumped and recharged periodically to prevent them from going rancid. She adds that many European operations prefer straight oils, which require minimal fluid maintenance and can be recycled, rather than water-dilutable fluids that require extensive fluid monitoring to ensure proper performance. She adds that forming operations typically don’t recirculate MWFs as much as cutting operations that use coolant flooding.

Another barrier to adopting compatible fluids, Lunn says, is that MWF formulation development is not driven by industry-wide specifications. Many suppliers, including small companies, provide fluids that are suited to the needs of individual customers, and even identical machines in the same shop can perform differently, she says. Purchasing managers often look at initial fluid purchasing costs, without factoring in long-term performance. Shop managers who are satisfied with the MWFs they have been using for years are naturally reluctant to risk changing to a new product.

Compatible fluids might make sense, Lunn says, when a customer is trying to simplify and consolidate their inventory of fluids or when they are experiencing problems with tool life and the resulting down time for maintenance and repairs. “You have to show some sort of benefit that’s directly related to the per-part cost or more efficiency in the process itself,” she adds. Large operations that use straight oils throughout could benefit from compatible fluids, Lunn says, because emulsion splitting and microbial growth would not factor into these systems.

Dual-purpose fluids can be used in certain applications such as screw machines and extrusion processes, Lunn says. Screw machines are notorious for leaking and require constant lubrication for bearings, gears and ways, which would contaminate the cutting fluid, she adds. These lubricants tend to be specific formulations that are designed to provide performance and compatibility with all the lubrication needs of the machines.

Extrusion processes are another example where contamination between hydraulic fluid and the extrusion lubricant is high, and using the same fluid for both would be ideal, Lunn adds. In this application, it is important to match the viscosity and compatibility of the extrusion lubricant to the requirements of the machine manufacturer. Using a dual-purpose fluid is fairly common in the industry in both of these applications, she says.

Not surprisingly, high initial cost can be a deterrent to adoption, even if the long-term benefits of compatible fluids for a given application have been demonstrated. “The price to convert an entire process, with all the MWF volume, plus all the process fluids (hydraulic, gear, bearing, etc.) would be very high,” says Fitzsimmons. He adds that it would probably be difficult to convince most U.S. customers to commit to such a conversion. “A customer’s system would have to be very well maintained and efficient to find value in this kind of concept,” he says.

Fitzsimmons explains that, at least in the U.S., he has not seen customer demand for systems featuring end-to-end compatibility between machine lubricants and MWFs, adding that this type of system might be more popular with European manufacturers. He adds that industry-standard maintenance fluids (lubricants for hydraulics, gears, morgan bearings, etc.) are made and sold at prices that are lower than for all-purpose compatible MWFs.

Converting an entire operation—lubricants for gears, spindles, slideways, hydraulics and the MWF itself—to ester-based oils has often been challenging economically or operationally, Jamali concurs. Consequently, many ester-containing or ester-based water-dilutable MWFs are designed to reject mineral (hydrocarbon) tramp oils from machine leaks; those oils then separate and can be removed by skimmers or coalescers before they destabilize the emulsion. However, he adds, with the broader availability of reasonably priced esters, a compatibility-by-design approach—aligning MWF and critical machine oils on an ester platform—has become increasingly achievable for operations willing to align the full fluid chain.

Willingness to adopt a compatible fluids strategy is not so much a function of Europe versus North America as it is the type of manufacturer, Dallons says. European manufacturers, typically automotive OEMs, commonly run large central lubricant circulation systems that focus on recycling fluids, an approach that lends itself to end-to-end fluid compatibility. In the U.S., smaller manufacturing shops and multiple fluid distribution networks are more common, but even these smaller operations are beginning to adopt compatible fluid products, he says. The semiconductor and electronics manufacturing sectors in the U.S. are especially interested in this approach, he adds, because the small droplet size typical of such products is well suited to small through-drills and fine filtration systems.

One sticking point for many potential customers is the time and investment involved in switching from their current machine, hydraulic and metalworking lubricants to an end-to-end compatible ester system. Dallons notes that customers could use conventional hydraulic and way oils with an ester emulsion MWF, but it wouldn’t be effective to use the ester hydraulic and way oils with a conventional emulsion MWF. He adds that the conventional method of using a refractometer to monitor the MWF condition would produce misleading results in this situation, indicating an apparently sufficient oil concentration but not registering the reduced MWF additive levels caused by way of oil dilution.

Most customers aren’t in a position to dump everything and start fresh, Dallons says, but they can implement a compatible ester fluid line in an incremental fashion. In operations that do not use a central circulation system for all machines, a customer can drain the MWF from one machine, test it for quality and then use it to top off the other machines. They also empty the reservoirs for the way lube in the corresponding hydraulic system and use that lubricant to top off the reservoirs for the other machines. After that one system is cleaned, the compatible ester fluids are introduced. It’s not necessary to completely flush the lines, Dallons says. Any residual tramp oil can be skimmed off and discarded during normal operations. This process can be repeated, one system at a time, until the entire operation has been switched over.

Why would an operation that’s been running successfully for many years using a conventional method want to make this type of change? There’s always room for improvement, Dallons says. Some customers adopt compatible ester oils for various parts of their processes, like way oils or tapping oils, while using a conventional semisynthetic MWF. He notes, however, that using an end-to-end integrated fluid system makes it simpler to monitor and maintain optimum oil and additive concentrations, regardless of the severity of the application or the production levels and MWF consumption characteristics of a specific machine. “You can use one product to do pretty much every application in a building,” he says. Because additive replenishment packages and water are generally less expensive than base oils, he adds, operations that can reclaim and recirculate oil from all sources can save significant amounts of money.

Lifecycle performance and cost analysis

Ester base oil prices remain a significant barrier to growth in demand for ester-based lubricants, especially in small and mid-sized industries, developing economies and other price-sensitive markets. However, operations involving high machine speeds and temperatures, including OEMs in the aerospace, automotive and industrial equipment industries, are increasingly adopting esters, with regulatory standards regarding emissions and used oil disposal as an added motivation.

5

The global lubricant ester market is predicted to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 2% from 2025 to 2035. China is predicted to lead this growth (3.1% CAGR), with Germany (1.4%) and the U.S. (1.1%) experiencing more modest growth rates. The U.S. and Canada dominate the lubricant ester market, and sustainability efforts are driving a strong increase in European and Asian demand.

5,6 Multifunctional lubricants are also gaining in popularity.

7

Performance and sustainability factors are also driving a rise in demand for water-dilutable MWFs. This market sector is anticipated to grow at a CAGR of almost 4% between 2025 and 2035, driven by performance-critical industry sectors including automotive, aerospace and machinery manufacturing. Growth in demand for water-dilutable MWFs is predicted to be greatest in China (5.3% CAGR, 2025-2035), India (4.9%) and Germany (4.5%). One recent analysis8 states that at present, water-dilutable MWFs represent only about 14% of the market, but these fluids have proven themselves essential for applications like cutting, grinding and precise machining. Barriers to adoption include concerns over microbial growth, high maintenance requirements and a lack of consistency in regional disposal regulations.

8

A convincing business case requires an apples-to-apples comparison between the traditional “remove tramp oil” model and an integrated compatible fluid program, Jamali says. A true total cost of ownership analysis should include upfront fluid costs; changes in tool life and first-pass yield; elimination or downsizing of separation hardware (capital, maintenance and energy); reductions in disposal volumes and changeout frequency; and labor and time saved through simpler maintenance. These factors must be balanced against the ongoing costs of managing conventional contamination.

Adoption dynamics vary, Jamali says. Large, high-consequence operations tend to be receptive because the cost of failure is high. By contrast, metalworking systems are sometimes treated as routine utilities, so perceived criticality can be lower, he notes. High-volume plants often realize the largest savings, which helps explain why some major manufacturers have been early adopters of compatibility-by-design strategies.

Jamali notes that some installations using compatible fluids report multi-year sump life. In at least one documented case, he adds, sump life under disciplined management exceeded a decade without a full change. “It’s hard enough to keep a MWF stable for one or two years,” he says. “What about 10?”

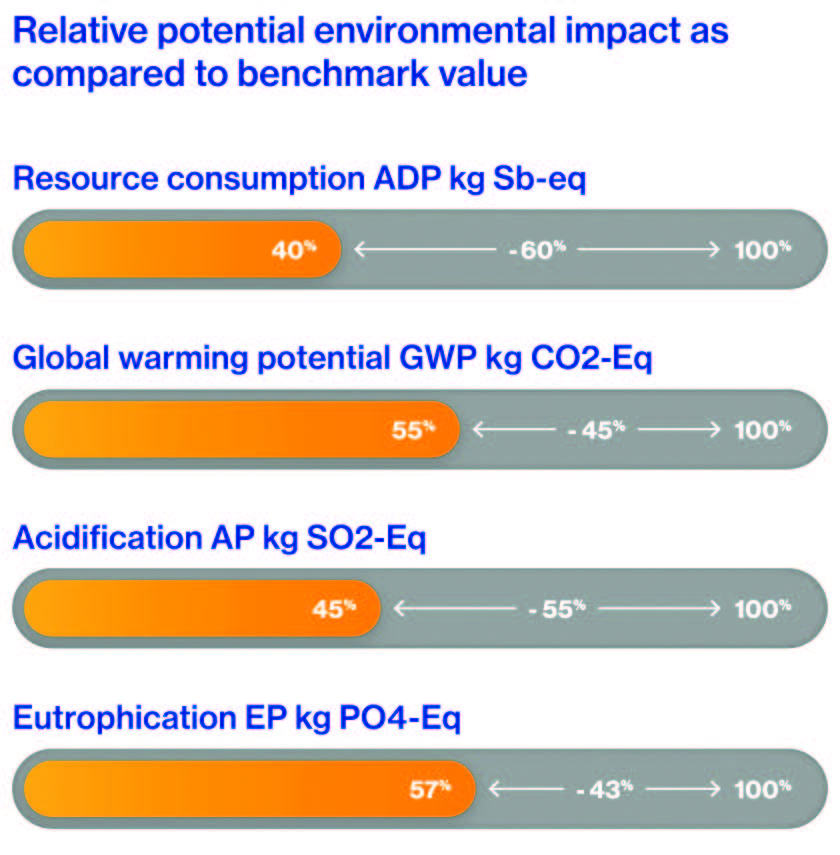

(See Compatible MWFs, by the Numbers.) Nevertheless, purchasing teams often focus on unit purchase price, he says. Pilot and lab demonstrations showing compatibility across MWF/tramp oil blends may not, by themselves, overcome sticker shock. Compatible MWFs can carry a higher drum price than conventional fluids—despite more favorable ester pricing—but a more strategic economic case hinges on lifecycle outcomes. For some companies, he adds, sustainability metrics (waste reduction, energy use, operator exposure) further tip the balance toward compatible fluids

(see Figure 3). For others, switching remains difficult when incumbent fluids appear to work at a lower upfront cost.

Compatible MWFs, by the numbers

How well does an end-to-end compatible fluid system work?

One large automotive customer with a total of 1.5 million liters in process currently uses a system that includes way lube oils, hydraulic oils and neat machining oils from the multi-function oil family. The parts made in this system are also cleaned with a cleaner from this product family that is recycled back into the central system as make-up rate, creating a true closed loop system.

This multi-function oil approach has enabled the customer to push the sump life to 10 years and running. The wash life has been extended from two weeks to 12 weeks. The customer has completely discontinued the disposal of fluid from the wash tanks because this fluid is recycled back into the central system, thus removing an additional 600,000 liters of waste annually.

Sidebar courtesy of Matthew Dallons.

Figure 3. The ester-type base oils used in end-to-end compatible systems (orange) can reduce an operation’s environmental impact in comparison with a mineral oil-based benchmark coolant (gray). ADP is abiotic depletion potential, in kilogram antimony equivalent units (kg Sb-eq). GWP is global warming potential (kg carbon dioxide equivalent). AP is acidification potential (kg sulfur dioxide equivalent). EP is eutrophication potential (kg phosphate equivalent). Figure courtesy of Oemeta.

With compatible oil systems, Dallons says, “you’re serving multiple purposes and replacing multiple products with a single product.” This not only simplifies and consolidates product inventories, but it also saves a customer money in the long run. The perception of higher cost “is a really big misunderstanding of the concept,” he says. “If you look at the prices up front, liter for liter and gallon for gallon, yes, it is probably going to be a little bit more expensive.” But, he explains, oil can leak from a hydraulic system into the MWF system and contribute to that oil rather than being discarded as waste. MWF that is rinsed off a part using a compatible cleaner is recycled back into the MWF system. “When you look at the total cost of ownership, the pricing is actually significantly less,” he says. “We find that consumption drops quite a bit because we can continue to recycle the product over and over again.”

For example, Dallons says, “You don’t really buy conventional way oil. You put it into one side of the machine, it drips through the machine, and it pours into the MWF. Then, you skim it off and you pay to take it away. So, you’re really renting it for the week or two that it takes to go through the machine.” In contrast, a compatible way lubricant that leaks into the MWF stream effectively tops off and recirculates with the MWF supply. Even though the initial cost of the one ester-based oil is significantly higher than the multiple conventional oils it replaces, he says, “every gallon of way lube that introduces itself into the sump replaces a gallon of MWF fluid that you would otherwise purchase.”

Advanced applications

Another way to mitigate costs is to limit the amount of lubricant required, the approach taken in minimal quantity lubrication (MQL) setups. Although contamination of MWFs by machine oils is more or less universal, contamination of machine tool lubricants by cutting fluids is an issue for MQL operations, especially if separation treatments have not been adequate or effective. One way around this problem is synthetic polyol esters, which can serve as multifunctional base fluids for both cutting lubricants and machine tool lubricants, as well as lubricants for spindles, slideways and hydraulic components, demonstrating better cutting performance than mineral oils. Very small quantities of highly effective additives help to minimize incompatibilities between additive packages in these systems.

9

MQL spray operations that use compatible additives pass workpieces directly from one operation to the next, without having to wash off the machine lubricant first, says Dallons. The MWF emulsion flood rinses the MQL lubricant off the workpiece, and the mixture is recirculated. This works even in operations like hard tapping, where a separate tapping fluid is applied. Rather than hand-cleaning the workpieces, an emulsion flood washes the tapping fluid into the sump without interrupting the process.

Dallons also cites current developmental efforts on methods that replace traditional straight-oil MWFs with emulsions for certain applications. Using a high oil content in a conventional semisynthetic MWF system would require such a high additive content that foaming and skin irritation would be significant problems. However, a water emulsion with a high ester oil content (20%-25%) can perform well with additives in the 3% to 4% range. This type of system offers the lubricity of a high oil content with the cooling capabilities of a water emulsion, he says, adding that this could be useful for applications like gun drilling or cubic boron nitride (cBN) grinding.

To switch or not to switch?

To switch or not to switch?

As is the case with so many other decisions, switching to end-to-end compatible lubricants, hydraulic fluids, MWFs and cleaners involves weighing numerous interacting costs and benefits. Do the long-term benefits outweigh the initial costs of purchasing the fluids and performing the changeover? Will the new fluids work as well and last as long as the old ones? Can the changeover be done incrementally, or does a centralized system require changing all the fluids at once? How well is the existing setup performing, and how likely is it that the fluids currently in use will be reliably available at a reasonable price in the future? As end-to-end compatible fluid systems become more widely used, the experiences of early adopters can provide a track record that clarifies the decision for other operations.

REFERENCES

1.

Sosa, Y. (2023), “Understanding and controlling water dilutable metal-removal fluid failure,” TLT,

79 (4), pp. 34-51. Available at

www.stle.org/files/TLTArchives/2023/04_April/Webinar.aspx.

2.

Miles, T. (February 17, 2025), “Sustainability and cost savings in one cutting-edge solution,”

Machinery Market, www.machinery-market.co.uk/news/39172.

3.

Two-component metalworking fluids. Oemeta product information page,

www.oemeta.com/us/products-services/two-component-metalworking-fluid.

4.

“What to know about tramp oil,” Denver Oil blog post, February 18, 2021,

www.denveroil.co/what-to-know-about-tramp-oil.

5.

“Lubricant Ester Market Outlook (2025 to 2035),” Fact.MR,

www.factmr.com/report/lubricant-ester-market.

6.

“Global Lubricant Ester Market Size To Exceed USD 1.19 Billion By 2035 | CAGR of 1.78%,” Spherical Insights,

www.sphericalinsights.com/press-release/lubricant-ester-market.

7.

“Synthetic Ester Lubricants Market Size, Industry Outlook Report, Regional Outlook, Growth Potential, Competitive Market Share & Forecast, 2025 – 2034,” Global Market Insights Report ID: GMI3948,

www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/synthetic-ester-lubricants-market.

8.

“Water-miscible Metalworking Oil Market Forecast and Outlook (2025-2035),” Future Market Insights Inc.,

www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/water-miscible-metalworking-oil-market.

9.

Suda, S., Wakabayashi, T., Inasaki, I. and H. Yokota. (2004), “Multifunctional application of a synthetic ester to machine tool lubrication based on MQL machining lubricants,”

CIRP Annals, 53 (1), pp. 61-64,

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-8506(07)60645-3.

Nancy McGuire is a freelance writer based in Albuquerque, N.M. You can contact her at nmcguire@wordchemist.com.