Meet the Presenter

This article is based on a webinar titled On the Mercurial Behavior of Ionic Liquids at Sliding Interfaces, hosted by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers’ (ASME) Tribology Division and presented by STLE member Dr. Filippo Mangolini on Sept. 19, 2024. Courtesy of STLE, this article captures the core insights from this ASME-organized event. For more technical content from the ASME Tribology Division Webinar Series, visit the ASME Tribology Division’s website at www.asme.org/get-involved/groups-sections-and-technical-divisions/technical-divisions/technical-divisions-community-pages/tribology-division.

Dr. Filippo Mangolini is an associate professor in the Texas Materials Institute of the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin, Texas. He received his master of science in materials engineering from the Polytechnic University of Milan, Italy. His doctorate is in materials science on the study of the surface reactivity of environmentally compatible lubricant additives from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland.

After obtaining his doctorate, he moved to the University of Pennsylvania as a Swiss National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow and received a Marie Curie Fellowship to continue his research in Pennsylvania. He received a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship for Career Development and moved to Ecole Centrale de Lyon in Lyon, France, then to the University of Leeds, UK, as a university academic fellow. The overarching goal of his research is to develop a physically based understanding of the structural transformations and chemical reactions occurring on material surfaces and at solid/solid and solid/liquid interfaces under extreme environments and conditions far from equilibrium. He can be reached at filippo.mangolini@austin.utexas.edu.

Dr. Filippo Mangolini

KEY CONCEPTS

•

Ionic liquids have high thermal stability, negligible vapor pressure and excellent lubrication properties, making them a promising class of fluids for a number of different applications.

•

Under pressure, these liquids can generate a lubricious solid-like interfacial layer that can reduce nanoscale friction or result in wear of the underlying substrate.

•

Understanding the nanoscale lubrication mechanisms can improve their performance.

•

Limitations to the use of ionic liquids include cost, corrosion, oil-miscibility, thermal oxidation and toxicity, but research is occurring to reduce and eliminate these problems.

Ionic liquids have attracted considerable attention in tribology owing to their high thermal stability, negligible vapor pressure and excellent lubrication properties. They are a promising class of fluids for a number of applications.

Inorganic ionic compounds are usually constituted of cations and anions that sit in specific locations in a crystal lattice. An example is table salt or sodium chloride (NaCl). The strong covalent interactions between the ions result in very high melting points for these compounds, higher than 100℃ and even above 1,000℃ in some cases.

Ionic liquids are still constituted by cations and anions with covalent bonds, but these ions are mostly organic. Ionic liquids have melting temperatures below 100℃, and in some cases even below room temperature. Examples of ionic liquids include ammonium, acetate, 1,3-substituted imidazolium, alkylsulfate and phosphonium, among many others. The unique properties of these compounds make them appealing in a number of fields.

This article is based on an ASME Tribology Division Webinar presented on Sept. 19, 2024, as an invited talk by Dr. Filippo Mangolini. See Meet the Presenter for more information.

Ionic liquids

Ionic liquids have unique properties, including high thermal stability, negligible vapor pressure, low flammability and a wide electrochemical window.

1,2,3 More than 10

18 ionic liquids theoretically exist.

4 These properties and the number of possible chemicals make the use of ionic liquids attractive in a number of different fields, including as:

•

Separation media for liquid membranes, extraction and carbon capture

•

Electrolytes in fuel cells, batteries, sensors, metal plating and solar cells

•

Working fluids for heat storage, lubricants and surfactants

•

Green solvents for biocatalysis, chemical processing and protein crystallization

•

Advanced materials in liquid crystal displays, artificial muscles and pharmaceuticals

Mangolini’s research group focuses on the structure and dynamical evolution of ionic liquids near solid interfaces. These topics are critical in energy storage, conversion materials, devices and lubrication. This webinar focuses on lubrication, especially the effect of nanoconfinement (i.e., when the ionic liquid is confined between two surfaces) and the lubrication mechanisms of ionic liquids.

Lubrication with ionic liquids

The effect of nanoconfinement on ionic liquids is measured in surface force apparatus (SFA) experiments, in which the applied normal pressure is usually less than 100 MegaPascal (MPa).

5,6 Thus, in SFA tests, the pressures are below that experienced by mechanical components in real world tribological applications; however, Mangolini notes that much can be learned from these experiments.

An example of this learning comes from studying the normal force, which is a function of the separation between two surfaces as they progressively approach each other.

7 Ionic liquids tend to be squeezed out discontinuously, in discrete steps. The discrete steps in normal force correspond to the squeezing out of electroneutral slabs constituted by a cation-rich and an anion-rich layer. As the number of ionic layers decreases, the kinetic friction force increases with the coefficient of friction.

At the macroscale, tribological experiments show that phosphorus-containing ionic liquids tribochemically react on steel and cast-iron surfaces.

8,9 Reaction layers formed by phosphonium phosphate ionic liquids are amorphous with a thickness between 120 and 180 nanometers (nm) and are composed of short chain iron polyphosphates.

This discrepancy between macro and micro scale experiments drew attention to the following questions:

•

What is the dependence of the lubrication mechanism of ionic liquids on the applied normal pressure?

•

What is the dependence of the lubrication mechanism and performance of ionic liquids on the ionic liquids’ molecular structure?

•

How can the limitations hindering the use of ionic liquids in lubricants be overcome? These limitations include corrosion, oil-miscibility, thermal oxidation, toxicity and cost.

Studying ionic liquid lubrication mechanisms

Mangolini’s group used a number of different techniques to study how ionic liquids work as lubricants at the atomic level at the contact points during steel-on-steel sliding. These techniques included atomic force microscopy (AFM), molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, X-ray photoemission electron microscopy (X-PEEM), time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) and low energy electron microscopy (LEEM). The processes and results of these studies are described in the following paragraphs.

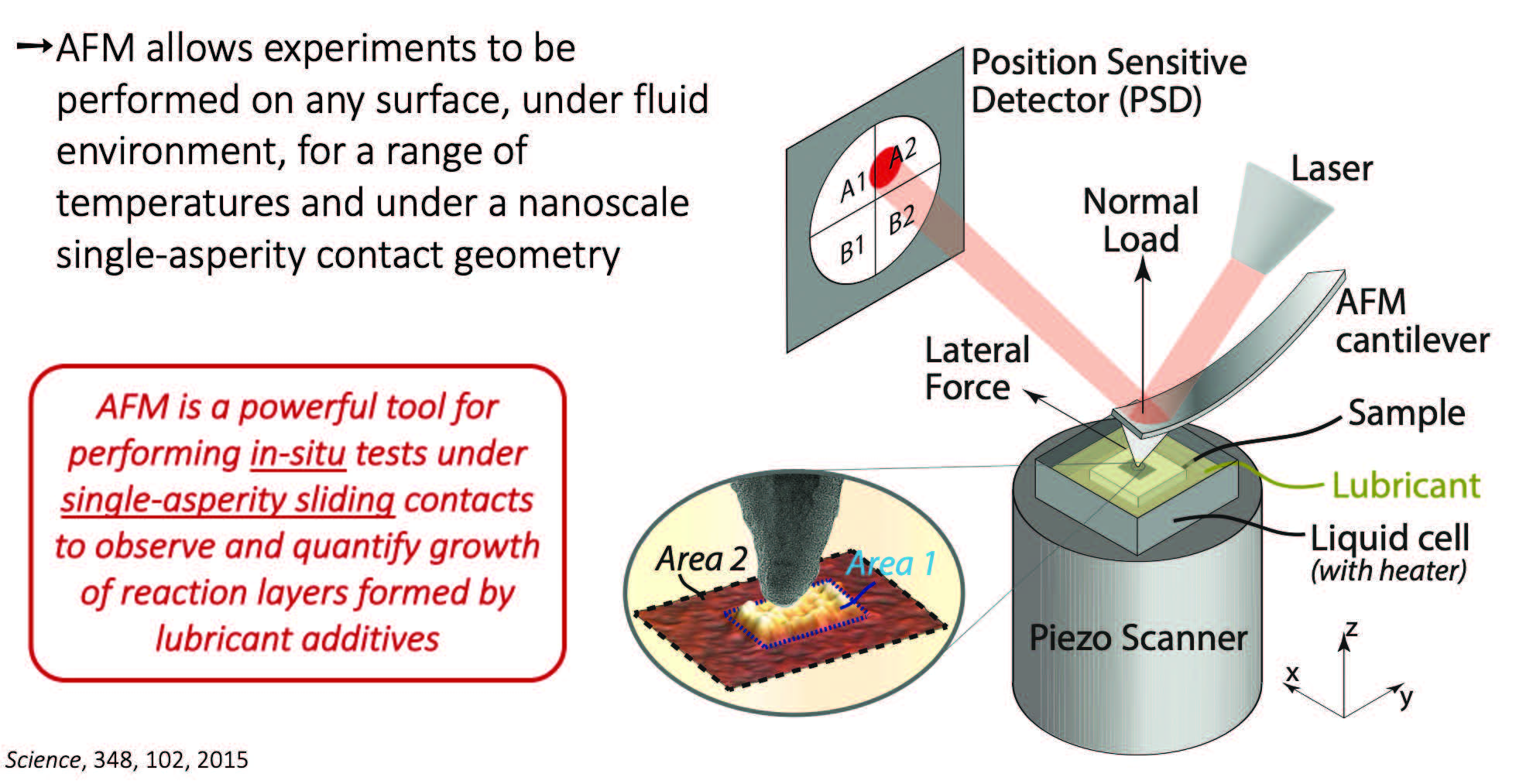

AFM is a powerful tool for the in situ investigation of the surface mechano-chemical reactivity of lubricants. AFM allows experiments to be performed on any surface, under fluid environments, for a range of temperatures, while under a nanoscale single-asperity contact geometry

(see Figure 1). AFM is a powerful tool for performing in-situ tests under single-asperity sliding contacts to observe and quantify the growth of reaction layers formed by lubricant additives.

Figure 1. Nanoscale single-asperity contact geometry.

Figure 1. Nanoscale single-asperity contact geometry.

For the experiments, Mangolini’s team used a diamond-like-carbon (DLC)-coated silicon AFM tip. The first series of experiments used phosphonium phosphate ionic liquid lubricant on steel under high applied pressure (up to several GigaPascal [GPa]) and temperatures of 110±1℃. The hypothesis was that these ionic liquids might form tribolayers under these pressures and temperatures and that the chemical reaction rate is dependent on the applied force and on the temperature.

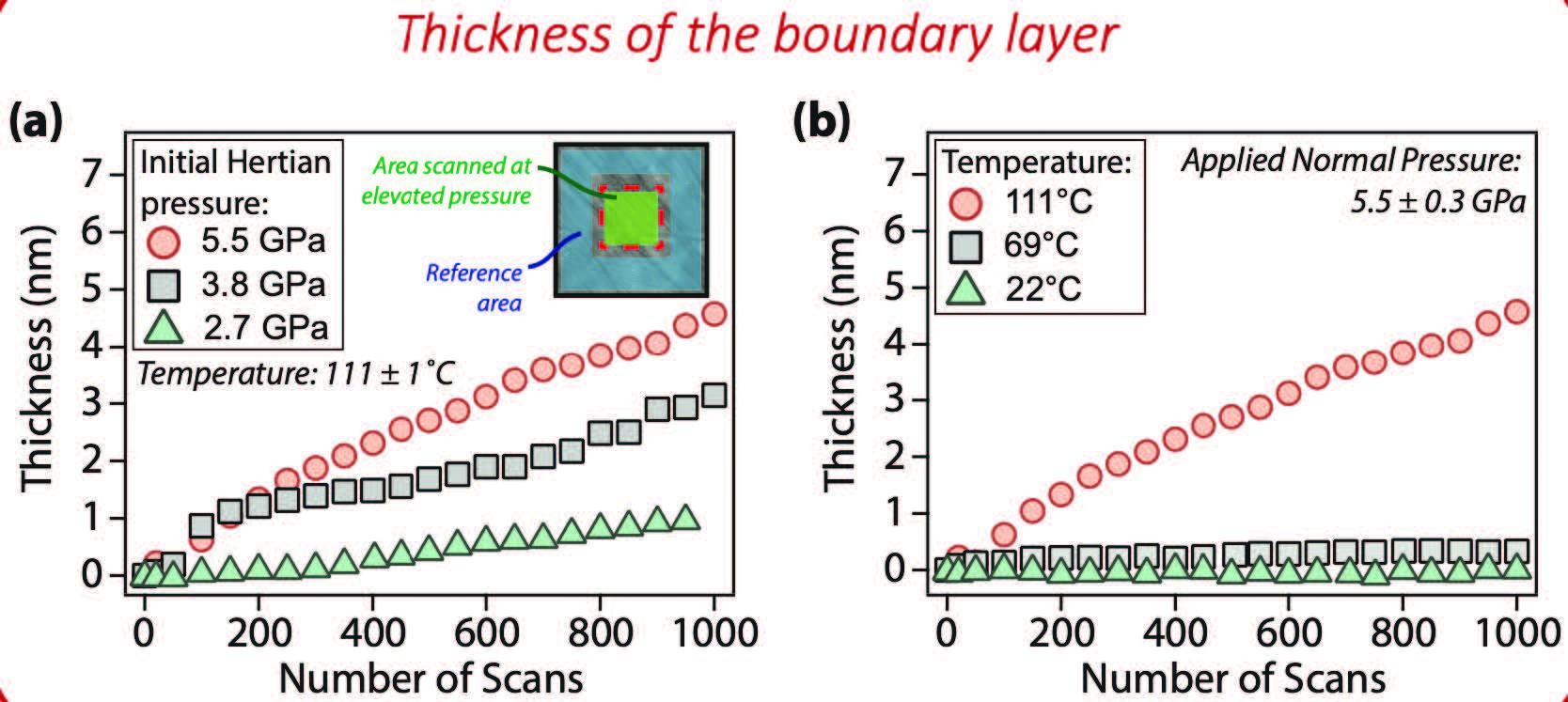

The experiment provided evidence for the pressure-dependent structural morphology of phosphonium phosphate ionic liquid on steel. Figure 2 shows multiple topography maps (out of 1,000 frames taken) of the stainless-steel surface together with friction force maps for an area scanned at 5.5±0.3 GPa. The maps show lighter colors as the experiment progressed, indicating the formation of layers on the steel surface with a corresponding decrease in friction force. After 100 frames, the formation of a lubricious layer in the area scanned at high pressure is clearly visible. The rate of formation of these layers is dependent on the temperature and pressure. That is, as the temperature increases when the pressure is held constant, the layer thickness increases. When the pressure increases while the temperature is held constant, the layer thickness also increases.

Figure 2. Multiple topography maps (out of 1,000 frames taken) of the stainless-steel surface together with friction force maps for an area scanned at 5.5±0.3 GPa. Figure courtesy of Li, Z., Morales-Collazo, O., Chrostowski, R., Brennecke, J. F. and Mangolini, F. (2022), “In situ nanoscale evaluation of pressure-induced changes in structural morphology of phosphonium phosphate ionic liquid at single-asperity contacts,” RSC Advances, 12 (1), pp. 413-419, https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA08026A.

This resulting film is a few nanometers thick and, when washed with a light solvent, the film was completely removed with no mechanical wear observed on the underlying air-oxidized steel substrate. In other words, no tribo-chemical reactions leading to the formation of inorganic iron phosphates occurred during the experiment.

MD simulations could provide atomistic insights into the underpinning lubrication mechanism. MD simulations of phosphonium-based ionic liquids at elevated hydrostatic pressures indicated a well-ordered, solid-like layering of the polar groups separated by the apolar cationic tails.

10 Mangolini’s team believes that the formation of the layer is the result of the spatial orientation of the ionic liquid under applied pressure.

To determine if this layer was mechanically stable, the same experiment was performed at high pressure (above 5.5 GPa). In this case, a thicker layer was not formed, and the substrate began wearing away as the friction force increased.

Further studies of the surfaces were performed using X-PEEM, which is a full field imaging technique combined with X-ray synchrotron radiation. X-PEEM is a surface-sensitive spectroscopic technique with excellent spatial resolution (<50 nm). These measurements were performed at the National Synchrotron Light Source II at the Brookhaven National Laboratory.

The results of the X-PEEM characterization of the sample used in experiments performed at high normal pressure (above 5 GPa) showed there was no major chemical difference when comparing the spectra from inside and outside the measurement area. In the specific experiment, the X-PEEM showed DEHP (di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate) anions and P

6,6,6,14 [trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium] cations were adsorbed on the steel surface with a slight enrichment of DEHP anions. These results indicate once again that there are no thermal or tribo-chemical reactions leading to the formation of inorganic (poly)phosphates.

These results were also confirmed by ToF-SIMS analyses, which are used to analyze the elemental and molecular composition of the outermost surface of a solid sample.

LEEM analysis allows for the determination of the local surface potential at each position on a sample (lateral resolution < 50 nm). Surface potential maps are obtained by measuring the intensity of specularly reflected low-energy electrons (0-100 electron volt [eV]) as a function of electron energy. The results suggest there is a change in surface electrostatic potential due to changes in the number density of surface-adsorbed ions, as well as their spatial orientation.

Putting all of these data together, the proposed model for the lubrication mechanism of phosphonium phosphate ionic liquid shows the system before sliding, sliding on iron oxide, sliding on iron and the friction measurement. When the applied pressure is too high, material starts being removed from the substrate. This exposes metallic ions and the absorption configuration goes from monodentate to bidentate as the ions are pushed to interact more with each other.

This work identified two distinct mechanisms controlling the lubricity of the phosphonium phosphate ionic liquids:

•

Formation of a boundary layer as a result of pressure-induced changes in structural morphology of the [P

6,6,6,14][DEHP] ionic liquid at pressures lower than 5.5±0.3 GPa

•

Generation of a densely packed boundary layer of surface-adsorbed phosphate ions on metallic iron at pressures >5.5±0.3 GPa

Impact of ionic liquid molecular structure on lubrication mechanisms and performance

To understand the impact of ionic liquid molecular structure, Mangolini’s team designed and synthesized a halogen-free boron-based ionic liquid, part of a promising class of ionic liquids for lubrication purposes. Halogen-free phosphonium orthoborate ionic liquids have good hydrolytic stability and are effective lubricants for steel/steel and steel/aluminum sliding contacts. The challenges include the presence of two glass-forming elements (i.e., phosphorus and boron), which pose significant challenges for fundamental tribological studies. In addition, orthoborate ionic liquids have negligible oil-miscibility.

To overcome this limitation, the group synthesized alkylammonium orthoborate ionic liquids with different chemical structure of the ions. Tribological tests indicated that the lubricating properties of alkylammonium orthoborate ionic liquids strongly depend on the cation and anion structures, while also displaying low corrosivity even though water is present in the system.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements allowed for evaluating the tribochemistry of alkylammonium orthoborate ionic liquids. XPS spectra of the steel surface used for tribological experiments with these ionic liquids do not show absorption of the ionic liquid on the steel surface. However, inside the wear track, the presence of boron and nitrogen was observed. A very low amount of boron and nitrogen was observed when friction was low, while a higher amount of boron and nitrogen was detected in the wear track in which high friction was measured. These results were interpreted on the basis of the structure of the ionic liquids used as lubricants. That is, ionic liquids with asymmetric cations do not tribochemically react on steel surfaces, but reduce friction by forming a lubricious, solid-like interfacial layer through pressure-induced morphological changes. Ionic liquids with symmetric cations do not prevent hard/hard contact owing to the weaker van der Waals interactions that stabilize the solid-like interfacial layer.

Overcoming limitations to use of ionic liquids in lubricants

The limitations to the use of ionic liquids in lubricants include corrosion, poor oil-miscibility, thermal oxidation, toxicity and cost. Mangolini focused on corrosion and oil-miscibility in the webinar.

Most ionic liquids for lubrication have poor solubility (much less than 1%) in nonpolar hydrocarbon oils.

9 Solutions to overcoming this problem include using oil-ionic liquid emulsions, low concentrations of ionic liquids in nonpolar base oils and polar base stocks to increase the ionic liquid solubility.

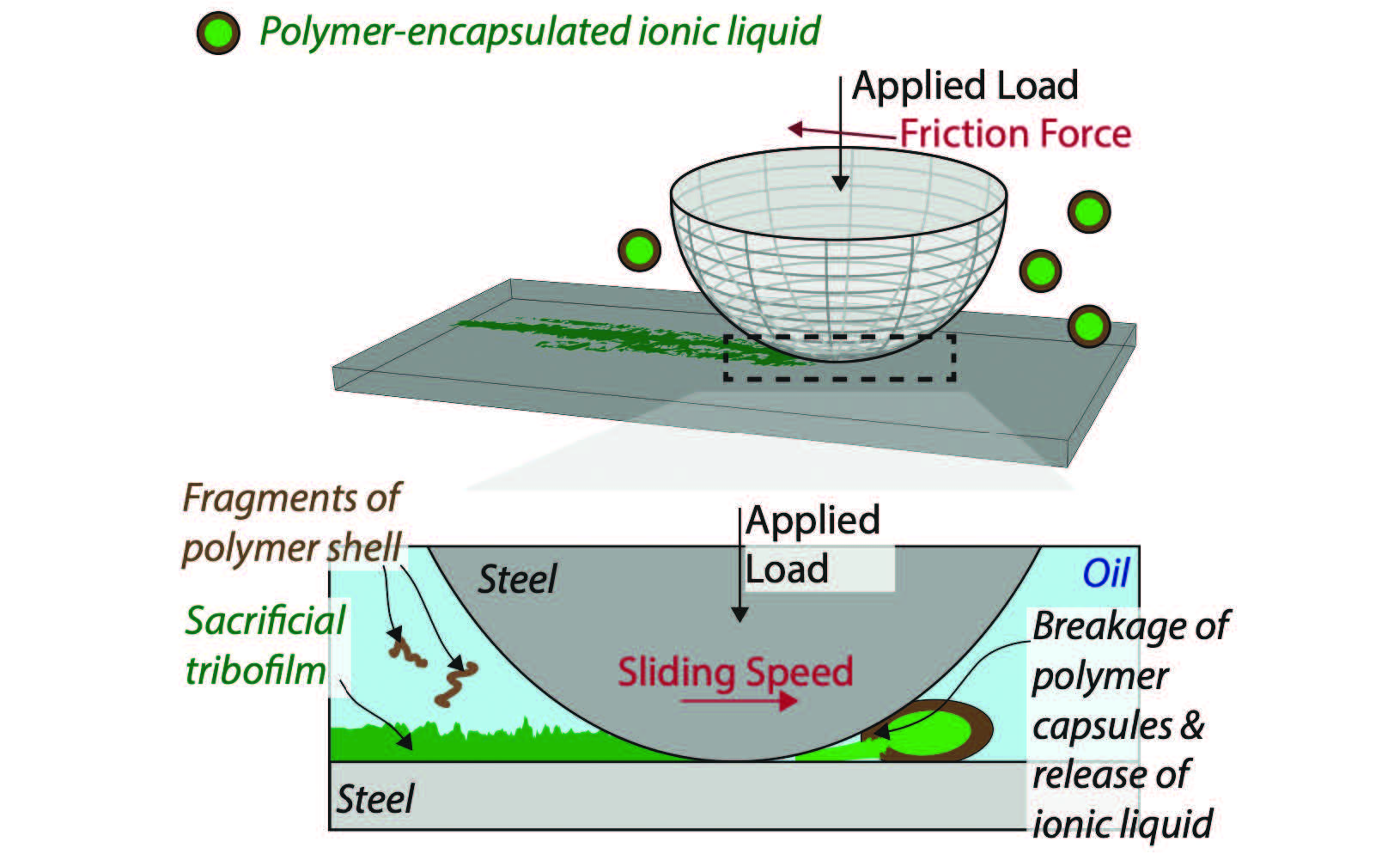

Encapsulating ionic liquids for lubrication purposes is not a new idea as it has been explored in a number of different fields, including waste handling and gas capture. Mangolini and his group hypothesized that the polymer capsules containing ionic liquids can be broken under pressure at the interface to release the lubricant

(see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The polymer capsules containing ionic liquids can be broken under pressure at the interface to release the lubricant.

Figure 3. The polymer capsules containing ionic liquids can be broken under pressure at the interface to release the lubricant.

Different methods have been proposed to encapsulate ionic liquids, including solvent evaporation, emulsion polymerization, Pickering Emulsion (i.e., interfacial polymerization) and impregnation. The team focused on emulsion polymerization and the resulting polymer shells were 4-5 microns in diameter with a shell thickness ranging from 0.2-0.4 micrometers (µm) with ionic liquid loading in the capsules ranging from 63-70 weight percent.

Reciprocating sliding experiments performed in the boundary-lubrication regime provided evidence for the effectiveness of the encapsulation approach in reducing friction, while also demonstrating that the ionic liquid released at the sliding interface following breakage of the polymer shell. However, further work is proceeding on this topic.

Conclusions

The experiments described in this webinar show that ionic liquids can be synthesized in a rational way to establish links between their molecular structure, lubrication performance and mechanics. The resulting emerging knowledge can enable the use of ionic liquids in lubrication applications. Furthermore, the encapsulation of ionic liquids in a polymer shell is an effective approach to overcome their limited solubility in nonpolar liquids.

Cost is still a problem when considering the use of ionic liquids as lubricants, but research is occurring on synthesizing and exploring amino-acid-based ionic liquids. These have the potential to be both inexpensive and biocompatible.

REFERENCES

1.

MacFarlane, D.R. et al. (2017),

An Introduction to Ionic Liquids.

2.

Matic, A. and Scrosati, B. (2013), “Ionic liquids for energy applications,”

MRS Bulletin, 38 (7), pp. 533-537.

3.

Plechkova, N.V. and Seddon, K.R. (2008), “Applications of ionic liquids in the chemical industry,”

Chemical Society Reviews, 37 (1), pp. 123-150.

4.

Hayes, R., Warr, G.G. and Atkin, R. (2015), “Structure and nanostructure in ionic liquids,”

Chemical Reviews, 115 (13), pp. 6357-6426.

5.

Israelachvili, J. (2011),

Intermolecular and Surface Forces.

6.

Drummond, C. and Ruths, M. (2016),

Encyclopedia of Nanotechnology.

7.

Smith, A. M., et al. (2013), “Quantized friction across ionic liquid thin films,”

Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 15, 15317-15320.

8.

Qu, J., Bansal, D.G., Yu, B., Howe, J.Y., Luo, H., Dai, S., Li, H., Blau, P.J., Bunting, B.G., Mordukhovich, G. and Smolenski, D.J. (2012), “Antiwear performance and mechanism of an oil-miscible ionic liquid as a lubricant additive,” A

CS applied materials & interfaces, 4 (2), pp. 997-1002. Available at

https://doi.org/10.1021/am201646k.

9.

Zhou, Y. and Qu, J. (2017), “Ionic liquids as lubricant additives: A review,”

ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 9 (4), pp. 3209-3222. Available at

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b12489.

10.

Sharma, S. et al. (2016), “Pressure-dependent morphology of trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium ionic liquids: A molecular dynamics study,”

The Journal of Chemical Physics, 145, article no. 134506.

Andrea R. Aikin is a freelance science writer and editor based in the Denver area. You can contact her at pivoaiki@sprynet.com.