Key aspects of tribology

By Andras L. Korenyi-Both, Contributing Editor | TLT Lubrication Fundamentals February 2026

Let’s start with a definition and provide the problem/opportunity statement.

Tribology is a word full of so much meaning and excitement for those of us who are practiced in the art, but it is a strange sounding group of letters to most. This irony is rather amusing and befuddling to tribologists, as the science and art of tribology are integral to everyday life, and the principles of tribology govern the ethos of the entire universe.

Asking people who are not connected or familiar with the field, what they think the word means, does come with many humorous and clever responses. Often these responses drift into completely unrelated fields—anthropology: the study of tribes or tribal tattoos, biology: the study of triplets or tropical biology, mathematics: the study of triangles or trigonometry, medicine: an uncurable disease, philosophy: an ancient religion—seemingly we all have our favorites. Reeling the conversation back in requires an appreciation for the naïve innocence and demonstrates the incredible opportunity we have in sparking understanding and interest for this beautiful and critical field that some of us devote our entire careers to.

Defining words allows for clear and concise meaning with brevity; depending on our generational classification a source for definition may be an elder, a dictionary, an encyclopedia, a Wikipedia or Google search, a tweet or recently an artificial intelligence (AI) conversation. Thus, our conversation around tribology fundamentals often starts with a definition and, as such, the key point in defining tribology is to provide the problem/opportunity statement first. The definitional statement is interacting surfaces in relative motion. It is by pondering this statement that we ignite the challenge of understanding motion, surfaces and subsequent interactions. Then with an evolving understanding we learn and practice how to best control these physical and chemical interactions for our own utility.

Beyond a definition there is also the etymology (a term that most likely is also surrounded by interesting misconceptions) of a word, which gives us further insight into the meaning via origin.

Addressing the etymology (of the word tribology) leads to some interesting facts. The origin is accredited to Peter Jost, who in 1966 in the UK published the Jost Report1 detailing the massive economic impact on the world’s economy brought on by friction, wear and lubrication as a mitigant. He incorporated tribos as the root word because in Greek tribos means “to rub.” Jost in his report estimated that wear, friction and corrosion cost the UK economy 1.1%-1.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) annually. With an assumed equivalence in U.S. industrialization to the UK and a current annual U.S. GDP of $30 trillion according to the World Bank,2 the economic impact of tribology today can be valued at $330 billion to $420 billion. For perspective, the NASA annual budget tops out at $25 billion.

Without a doubt the challenges and opportunities of tribology have an economic impact, but beyond this we also have a tremendous environmental incentive to raise awareness, develop understanding and apply novel solutions to reduce waste and pollution. In 2018 the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) released a tribology report3 for enhancing U.S. energy security with two key findings.

1. Approximately 30% of energy consumed in just transportation is lost to friction and wear.

2. Implementing current tribology best practices in surface engineering and advanced lubricants can save ~11% of energy used across all industrial sectors including transportation.

Though we have made progress since 2018 there is still lots of exciting work to be done.

Motion, as the first key aspect of tribology on a mesoscale, is also a key aspect to our understanding of the universe as everything is in constant motion; the celestial bodies move toward or away from each other surrounded by a vast plasma of ionized gas known as Baryonic matter. This universal motion is also happening on a nanoscale where atoms and atomic constituents are interacting in relative motion in the bulk or on surfaces highlighting the multidisciplinary and universal nature of tribology, encompassing many disciplines: physics, chemistry, mathematics, materials science, chemical and mechanical engineering, to name a few. With a clear understanding of the fundamental relevance, framework and importance of tribology, the opportunities for global impact are endless. Moving mechanical assemblies from something simple as a nut and screw to a complex machine, such as the James Webb Space Telescope, define the machines of the post-industrial revolution era and, thus, within one arm length of anywhere we are, there is a compelling tribological phenomena with a clever solution already in existence or waiting to be solved. Dividing motion into classifications can be helpful because there is no universal panacea for all the opportunities that relative motion of interacting surfaces presents.

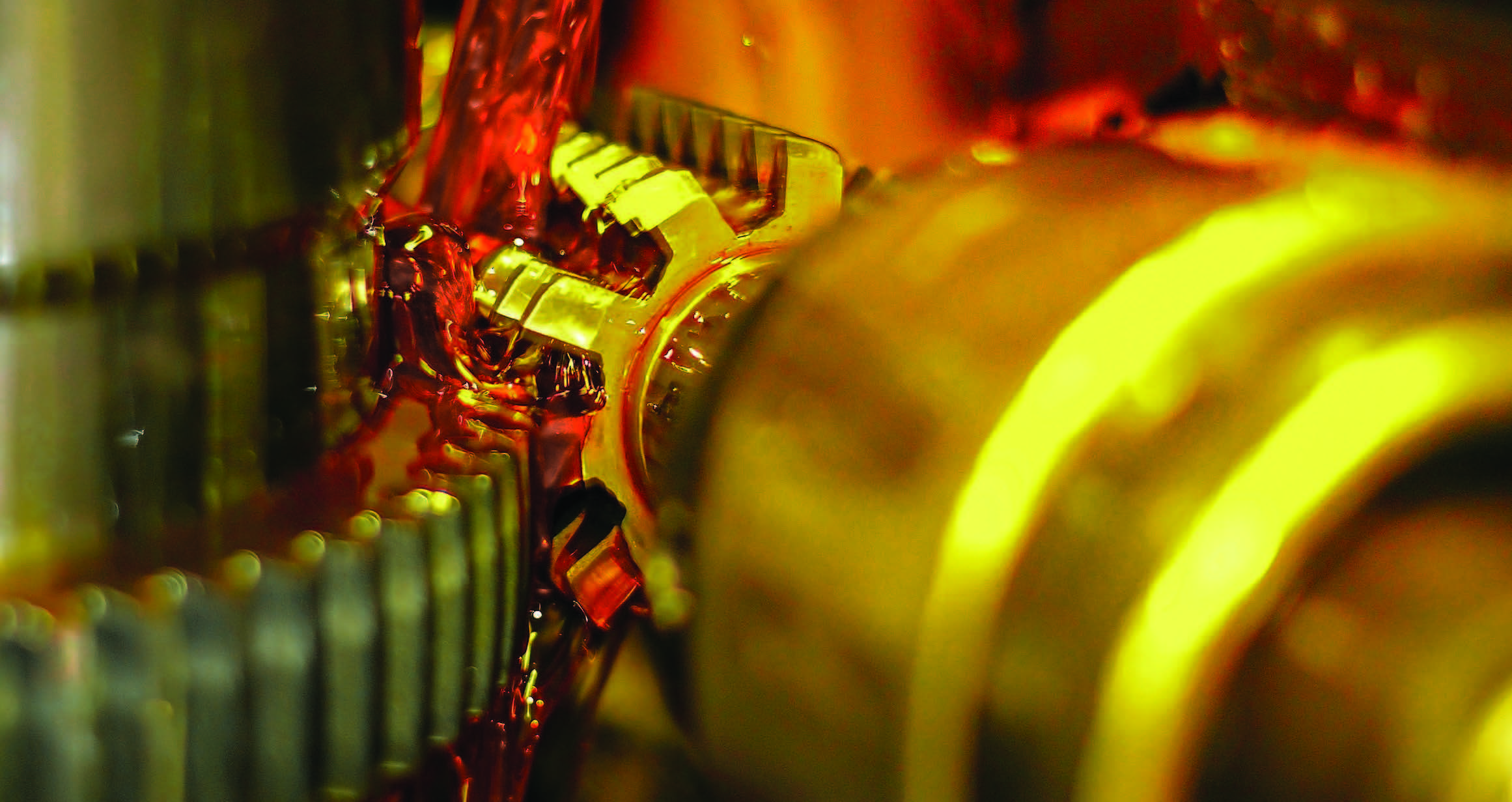

By far the most common motion in moving mechanical assemblies is sliding motion, but there are several other types and sometimes a combination of types. Generally, beyond sliding in broad classifications is rolling and impact. Rolling, as the name implies, allows bodies to roll past each other and provides a tremendous mechanical advantage versus sliding in most applications. Impact can be solid, large masses, small particles or a liquid of a given viscosity, all at various angles. Liquids can also cause cavitation wear. Sliding and rolling can be combined like in a gear system, or sliding can reciprocate on a very short length scale for fretting motion. If corrosion is combined with another wear mode, known as tribo-corrosion, the system is immensely complex and often the ensuing damage is very severe.

So, beyond the terms relative motion defining tribology is the equally important concept of surfaces, and not just surfaces but interacting surfaces. These surfaces can be the same or different but nonetheless come into contact with each other to transfer motion, or even in some cases slow or stop motion. Surfaces can be viewed throughout all the length scales, but ultimately the interactions are always on a nanoscale, and these surfaces and interactions can be highly complex. The complex nature of surfaces, compared to the bulk, is mostly driven by the highly variable environment in which surfaces exist. In relation the bulk is more uniform and predictable causing the Nobel Prize physicist Wolfgang Pauli to declare “God made the bulk; surfaces were invented by the devil.”

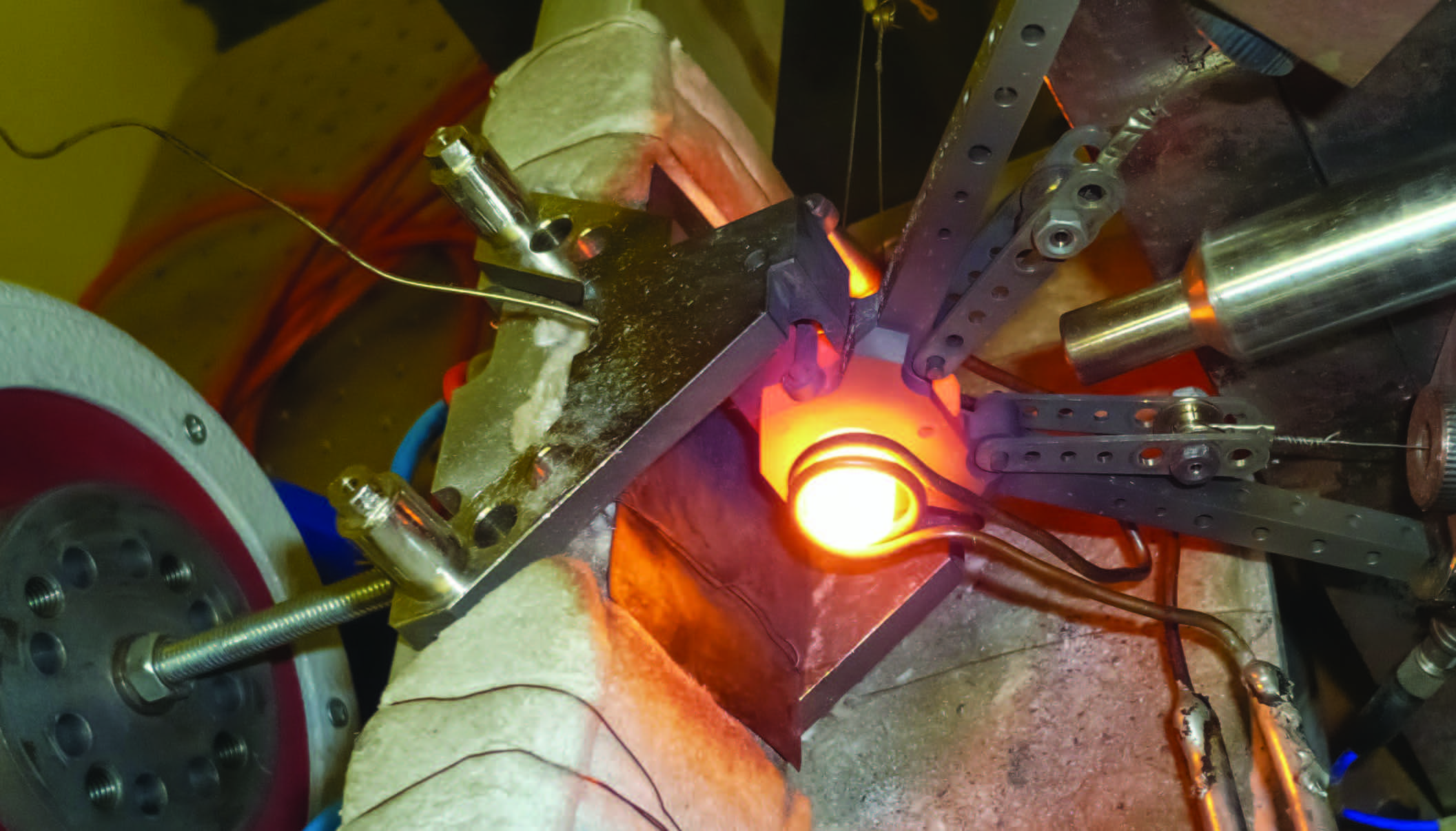

In modern tribology labs we have the capability to measure the chemical and physical properties of surfaces with surface science techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Raman spectroscopy or X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), to name a few. Beyond the chemical reactivity of a surface the topography is vitally important. Metrology techniques such as contact profilometry and non-contact 3D white light profilometry allow for detailed qualitative and quantitative surface topography data. Most often, poor part form or a peaky surface will cause very high contact pressure in a moving mechanical assembly and ushers in high stresses that lead to wear as the surfaces are brought into contact with each other. Measuring, controlling and even modifying these surface features brings the opportunity for surface engineering—for example, laser surface texturing or mass finishing to dial in surface characteristics to reduce both fiction and wear.

Armed with a clear understanding of relative motion and interacting surfaces as the landscape of tribology, we can move on to the other fundamentals, which are friction, wear and lubrication. Not only do we need to define these three key tribological phenomena, but we must know how to measure the forces of friction, the magnitude and type of wear and the efficacy of lubrication.

Friction, which most times but not always (traction) as tribologists we seek to reduce, is a force that resists motion. It can be further broken down into static friction, the force that must be pushed passed for motion to take place, or dynamic friction, the force that once motion commences is resisting the said motion. There is a related engineering term, the coefficient of friction (µ), which is the ratio of the tangential fiction force divided by the input force, though this is not a material property but a system property, and is useful in machine and lubricant design.

Wear, simply put, is a loss of material due to relative motion of interacting surfaces, and unless we are machining a part, it is generally undesirable. Wear is a such a ubiquitous phenomenon that it is part of a modern expression for being tired, “worn out.” Wear, much like friction, is not a material property but rather a system property and is generally measured using metrology or gravimetric techniques and expressed as a volume loss or missing material. Because wear is complex and typically occurs in a nonlinear fashion, there is no universal formula that relates wear to friction as the interactions are so complex and system/environment dependent. In fact, some material systems can have low friction and high wear, like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or low wear and high friction like physical vapor deposited (PVD) hard coatings. There are also some general wear modes that can exist on their own or sometimes in combination. There is abrasive wear, probably the most common, where a harder material or wear debris cuts or scratches, followed by adhesive wear, where this mode is dominated by chemical interactions and shearing. Erosive wear is caused by particles or fluid impinging on a surface. Impact wear is controlled by repeated cyclic impacts and fretting wear happens with very small amplitude and high frequency motion, while fatigue wear is usually caused by repeated cyclic high stresses such as rolling contact fatigue.

Once an anticipated or measured type of wear is detected a mitigation strategy can be developed. This strategy is best employed in early design stages versus a corrective action based on failure analysis. The most effective way to reduce wear is to not allow the interacting surfaces to come into intimate contact, and the best strategy for this is known as a lubricant.

A lubricant’s primary function is to provide separation of surfaces, and if it is a liquid, it can also provide cooling as an added benefit. The interaction of surfaces with a stable liquid lubricant is governed by the well known Stribeck curve, which shows the nonlinear nature of surface interactions and the categories of boundary lubrication, mixed lubrication and hydrodynamic lubrication with relation to liquid lube film shear. Other types of lubricants are greases, solid films or gas films. When a lubrication strategy is successfully deployed a moving mechanical system will function as designed and often beyond its expected life. Each type and sub type of lubricant has specific characteristics that must be carefully matched to the operating conditions. Considerations for lubricant degradation and strategies to keep the lubricant in the contact zone are critical.

Finally, another term that sometimes raises eyebrows of disbelief for not being a bona fide term is “tribometer.” This is a bench top laboratory mechanical test machine that can reproduce relative motion and surface interactions with a highly controlled set of input conditions. These test machines are not necessarily designed to model moving mechanical assemblies (though sometimes they can) but rather to provide a statistically relevant set of comparative results. For example, a four-ball tester can determine if a new additive in a grease provides an increase or decrease in wear by measuring wear scars, when the tribometer is run under identical conditions. Tribometers are as diverse as wear modes, but some common ones found in laboratories are pin-on-disk sliding, reciprocating, fretting, abrasion, impact and hard particle erosion. Tribometers provide useful information about materials, surfaces and lubricants and are useful for deriving specific wear rates and friction values for a given system setup. Industry specifications can be found to help align tribometer operating modes, data generation and interpretation. Examples include ASTM G-99 for pin-on-disk testing and ASTM G-133 for reciprocating testing.

Nature has found many clever ways to deal with friction, wear and lubrication, and sometimes we can take inspiration from nature for solving tribology problems, a field known as biomimetics. Human history, too, is rich with monumental accomplishments, many related to tribological challenges solved with ingenious solutions, but it has been only during the last 75 years that the field has gained attention and classification as a true science. The opportunity to accelerate discoveries and improve the functionality of moving mechanical assemblies has incredible potential. Powerful computational simulation, organized laboratory practices, machine learning combined with learnings from the field allow us to embrace a future with high efficiencies and low waste.

Having presented the key aspects of tribology such as motion, surfaces, wear, friction and lubrication, upcoming articles will dive deeper into each of these interrelated and fascinating areas. Stay tuned.

REFERENCES

1. Jost Report (1966), Lubrication (Tribology) Education and Research: A Report on the Present Position and Industry’s Needs, Great Britain; Department of Education and Science, HMSO: London, UK.

2. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=US

3. Fenske, G., Demas, N., Ajayi, L., Erdemir, A., Lorenzo-Martin, C., Eryilmaz, O., Erck, R., Ramirez, G., Storey, J., Splitter, D., West, B., Toops, T., DeBusk, M., Lewis, S., Huff, S., Nafziger, E., Thomas, J., Kaul, B., Qu, J., Cosimbescu, L, Zigler, B. and Luecke, J. (2018), “Final Report for U.S. Department of Energy Fuels & Lubricants Project on Lubricant Technology – Innovation, Discovery, Design, and Engineering,” Argonne National Laboratory, DOE Report, https://doi.org/10.2172/1507137.

Andras L. Korenyi-Both is Woodward Senior Technical Fellow Tribology at Woodward Inc. in Fort Collins, Colo. You can reach him at andy.korenyi-both@woodward.com.