HIGHLIGHTS

•

LPSCl is used as a solid-state battery electrolyte but suffers from instability in the presence of oxygen and moisture.

•

Application of alumina, as a protective layer on LPSCl, helps to stabilize the electrochemical performance but does not eliminate decomposition.

•

The alumina coating acts as both a physical barrier to decomposition and also affects the chemical composition of LPSCl. The ideal coating thickness to maximize conductivity and provide protection against degradation is one nanometer.

Research is ongoing to improve the performance of solid-state battery electrolytes due to their potential for providing a safer operating environment compared to liquid electrolytes. One of the solid-state battery electrolytes that is under evaluation contains lithium, phosphorus and chlorine and is known as LPSCl (Li

6PS

5Cl).

A previous TLT article

1 describes a research program that involved improving the manufacture of flexible solid-state lithium battery electrolytes. A polyisobutylene polymer binder was selected to impart structural and mechanical stability in a slurry process used to prepare the solid-state electrolyte. Differences in the polymer’s molecular weight impacted the volumetric changes and cracks detected during lithiation and delithiation of NMC 811 cathode used. Higher molecular weight polyisobutylenes were found to provide better performance and may even lead to doubling the battery’s energy storage.

LPSCl is used as a solid-state battery electrolyte due to performance and processing reasons. Dr. Justin Connell, materials scientist, at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Ill., says, “LPSCl is very ionically conductive meaning this electrolyte will promote ion charge transfer between the battery’s electrodes. Roll-to-roll processing has emerged as an attractive battery manufacturing technique. LPSCl has the necessary properties to be used in this technique without the need for sintering at high temperature.”

But a significant hurdle to commercializing solid-state battery electrodes is their stability in the presence of oxygen and moisture. Connell says, “LPSCl is environmentally unstable and difficult to stabilize. Its instability dictates that LPSCl must be handled in an environmentally controlled dry room with a dew point below -40℃. Interaction with moisture even at levels in the parts-per-million range can lead to decomposition to toxic hydrogen sulfide gas due to permanent sulfur loss. Other degradation products that form include phosphates, sulfates and lithium carbonate. LPSCl is also not stable at high voltages because that leads to chloride ion oxidation resulting in degradation of the solid-state battery electrolyte.

Past efforts to stabilize LPSCl have included tuning the surface chemistry of the electrolyte, structural modifications and altering the material’s electronic structure. One other option was to apply a protective coating. Connell and his colleagues started working with alumina which was applied via atomic layer deposition (ALD). He says, “We worked with alumina because it is the most widely developed ALD coating at this time.”

The researchers have now moved forward to better understand the effectiveness of alumina coatings and the mechanism for how they protect LPSCl.

Surface and bulk chemical stability

To better understand how alumina coatings protect LPSCl, the researchers prepared a series of coated solid-state battery electrolyte powders that differ in the thickness of the atomic layer deposition layers. The amount of applied coating was quantified based on the number of atomic layer deposition coating cycles. Each cycle led to the introduction of a 0.1 nanometer thick coating. Initial work was conducted with LPSCl treated with one and ten (a thickness of 1.0 nanometer) cycles.

LPSCl pellets were exposed to 22% relative humidity ambient air for 15 minutes and then evaluated for conductivity performance by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and for changes in chemical properties by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Results showed that the alumina coating helped to stabilize the electrochemical performance of LPSCl but did not completely stop it.

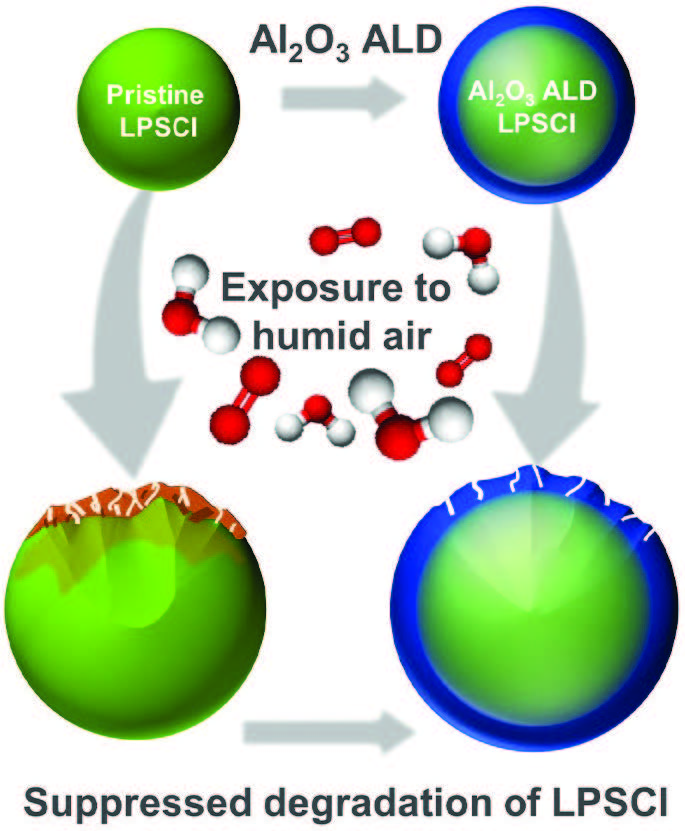

A schematic illustrates how the alumina coating reduces the degradation of LPSCl is in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Application of alumina (Al2O3) via atomic layer deposition (ALD) reduced the vulnerability of the solid-state battery electrolyte, LPSCl, to oxygen and moisture degradation. Figure courtesy of Argonne National Laboratory.

Connell says, “We measured electrochemical performance based on determining the area-specific resistance (a material’s resistance normalized by its surface area). Uncoated LPSCl displayed a 200 times increase in area specific resistance while the coated solid electrolyte displayed just an 80 times increase. The coating has a significant effect in improving the atmospheric stability of LPSCl.”

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy results clearly demonstrate that atomic layer deposition of alumina enhances surface chemical stability of the LPSCl. Fewer and lower concentrations of decomposition products were detected.

Evaluation of the bulk chemical stability of LPSCl was carried out using X-ray absorption spectroscopy. This analytical technique detected oxidation in uncoated LPSCl after exposure to humidified oxygen (100% relative humidity) for two hours. In contrast, little bulk reactivity was found in LPSCl that was protected with a one nanometer coating of alumina.

This study has now shown that a coating applied to LPSCl acts as both a physical barrier to decomposition and also affects the chemical composition of the solid-state battery electrolyte. Connell says, “While there is a direct correlation between the degree of physical protection and coating thickness, it does have limits. A drop-off in ionic conductivity, which is essential for electrolytes to function properly, is observed with coatings greater than 10 nanometers in thickness. The ideal coating thickness to maximize conductivity and provide protection against degradation is one nanometer.”

From the bulk chemical standpoint, the decomposition products also declined for coated versus uncoated LPSCl. A favorable aspect is that the dominant decomposition products found in coated LPSCl were able to contribute ion conductivity enabling the solid-state electrolyte to continue to be a conduit for ion transport between the electrodes.

Connell says, “The outcome from this phase of our work is that less stringent environmental conditions are now possible to use LPSCl in the manufacture of solid-state batteries because the alumina coating will be able to handle the presence of oxygen and moisture for a short-period of time. For the future, we are looking to scale-up the coating of LPSCl so that manufacturing on a commercial scale becomes feasible. We are also evaluating new coatings to determine their effectiveness as compared to alumina.”

Additional information on this work can be found in a recent article

2 or by contacting the Media Relations Department at Argonne National Laboratory at

media@anl.gov.

REFERENCES

1.

Canter, N. (2017), “Flexible solid-state lithium battery electrolytes,” TLT,

81 (2), pp. 16-17. Available at

www.stle.org/files/TLTArchives/2025/02_February/Tech_Beat_III.aspx.

2.

Kim, T., Hood, Z., Sundar, A., Mane, A., Lagunas, F., Kumar, K., Sunariwal, N., Cabana, J., Tepavcevic, S., Elam, J., Zapol, P., and Connell, J. (2024), “Suppressing Atmospheric Degradation of Sulfide-Based Solid Electrolytes via Ultrathin Metal Oxide Layers,”

ACS Materials Letters, 6 (12), pp. 5409-5417.