The Aerodynamic Leidenfrost Effect (ALE) describes the levitation of a liquid over a metal surface under sufficiently high-speed operating conditions due to formation of a layer of air entrained between the surface and the lubricant.

A new study assessed how ALE influences the ability of lubricants to spread on bearing surfaces under high-speed conditions.

Evaluation of three lubricants using a custom-built high-speed bearing rig found that the oils remained in contact with the ball up to speeds of 12,000 rpm but then lost contact at higher speeds.

High-speed operations are growing in use because they lead to greater efficiency and productivity in applications such as electric vehicles (EVs) and machine tools. As a result, gaining an understanding of the flow of lubricants in components such as high-speed bearings is becoming increasingly important.

STLE member Dr. Ujjawal Arya, postdoctoral research associate at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., says, “Rolling-resistance in high-speed bearings operating at DN values greater than 1 M can represent up to 40% of the energy supplied to EVs. Under high speeds, strong aerodynamic and centrifugal forces disrupt lubricant films and hinder oil adherence, leading to oil depletion and, ultimately, loss of effective lubrication.”

Film formation is critical for lubricants to minimize friction and wear in high-speed operations. Arya says, “A lubricant needs to display strong adherence to moving parts particularly at high-speeds to be effective. For bearings, surface speed, lubricant properties and surface finish are key parameters that will dictate whether a lubricant is successful.”

From the aerodynamic standpoint, a phenomenon known as the Aerodynamic Leidenfrost Effect (ALE) is influential in determining whether a lubricant can function in high-speed applications. STLE member Joe Misenar, master of science research assistant at Purdue University, explains, “The ALE involves the levitation of a liquid over a metal surface under sufficiently high-speed operating conditions. This phenomenon arises because a layer of air is entrained between the surface and the lubricant. The air creates a cushioning effect at high enough speeds that forces the lubricant to lift off from the surface.”

The Leidenfrost effect was first discovered in the 18th century by Johann Leidenfrost, a physician and theologian. Leidenfrost discovered that water, when placed near a heated material, levitates above its own vapor. In a previous TLT article,

1 researchers demonstrated that the ability of water to act as a heat transfer fluid can extend this substance’s boiling point. The key to achieving this result was to introduce a three-phase Leidenfrost effect where ice levitates on its melt water which, in turn, levitates on its evaporative vapor layer. Beneficial nucleate boiling of water was extended which improves heat transfer efficiency.

The ALE was first observed about 40 years ago in a rotating bearing study by Prahl and Hamock.

2 To gain a more fundamental understanding, Arya, Misenar and STLE Fellow Dr. Farshid Sadeghi, Cummins Distinguished Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Purdue University, conducted a comprehensive experimental and numerical study to assess how the ALE influences the ability of lubricants to spread on bearing surfaces under high-speed conditions.

High-speed bearing test rig

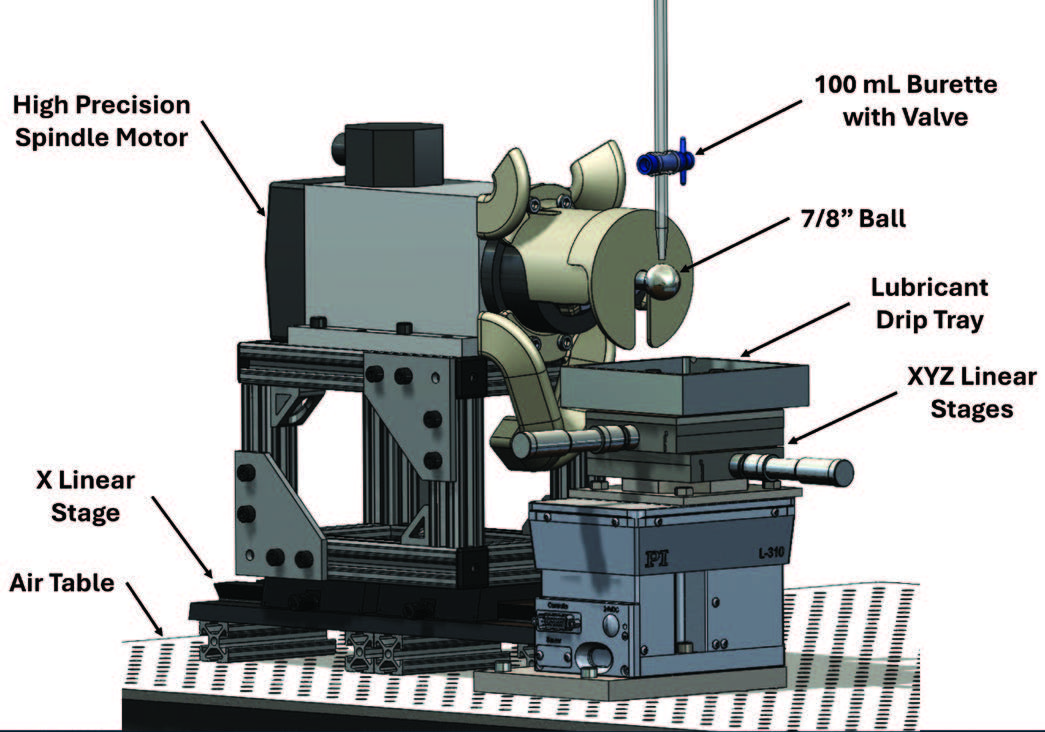

The researchers evaluated how rotational speed impacts the ALE by investigating different bearing components, lubricants and surface finishes. Figure 1 is an image of the custom-built high-speed bearing rig used in the study. The rig contains a 2.2-kilowatt high-speed motor capable of reaching up to 24,000 rpm. Experiments were conducted separately with an inner raceway and an outer raceway from deep grove ball bearings.

Figure 1. This high-speed bearing test rig, developed by the Mechanical Engineering Tribology Laboratory (METL), Purdue University, was used for analysis of the Aerodynamic Leidenfrost Effect (ALE). Figure courtesy of Purdue University.

Figure 1. This high-speed bearing test rig, developed by the Mechanical Engineering Tribology Laboratory (METL), Purdue University, was used for analysis of the Aerodynamic Leidenfrost Effect (ALE). Figure courtesy of Purdue University.

Arya says, “We initially evaluated a MIL-23699 lubricant on the surface that was introduced into the test rig at a flow rate of 2.94 milliliters per minute which resulted in the formation of droplets with an estimated radius of 1.7 millimeters.”

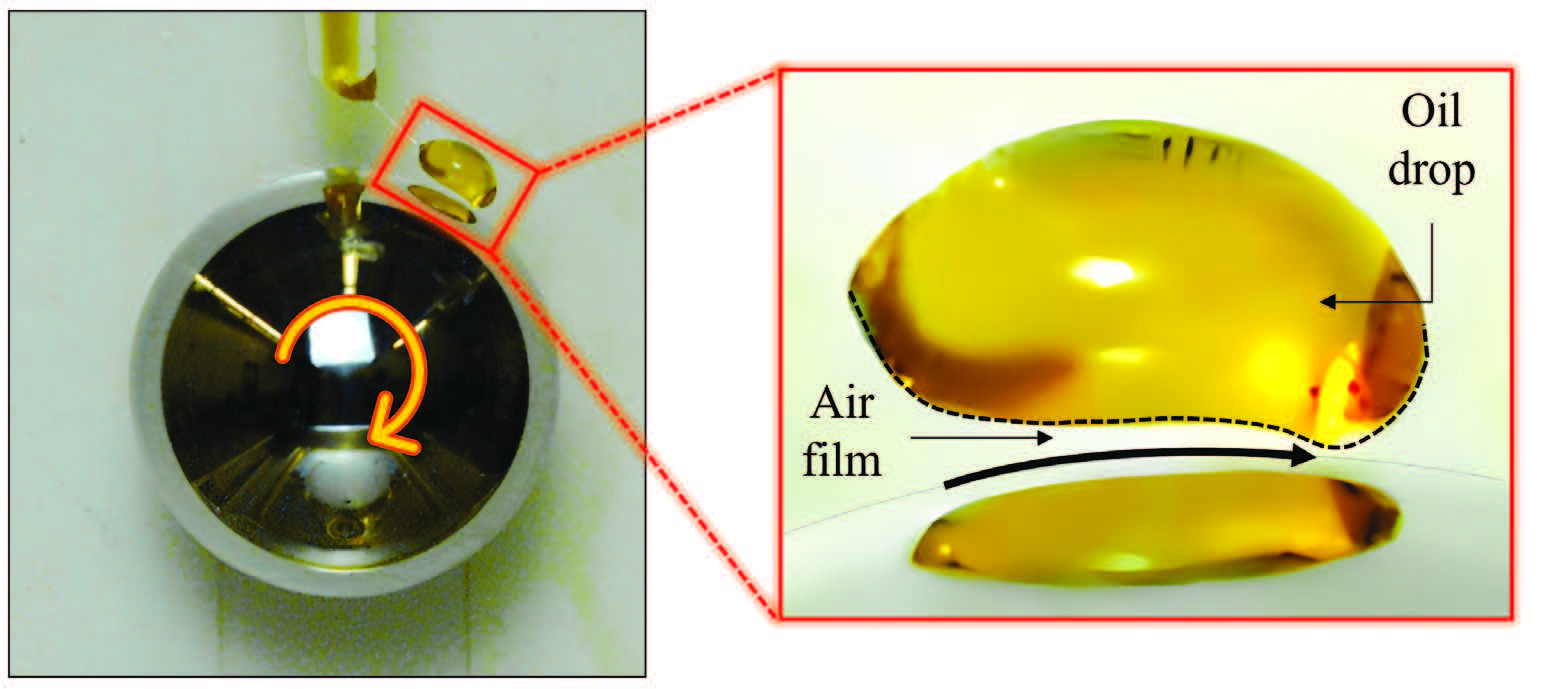

At speeds up to 12,000 rpm, the lubricant was effective in keeping contact with the ball. The lubricant drop spreads and adheres to the bearing surface while stretching along the rotational direction. But at higher speeds, beyond the threshold Leidenfrost velocity, the oil droplet no longer remained in contact with the ball.

Arya explains, “The reason for this observation is due to the formation of an air film enveloping the ball surface due to ALE, preventing the oil from contacting the surface. As the speed of the rotating ball rises to 24,000 rpm, the entrained air present between the ball surface and the lubricant increases in thickness, causing a further increase in lift force.”

Further experimentation was conducted with the MIL-23699 oil and two other lubricants, a low viscosity EV fluid, and a 75W-140 oil at 24,000 rpm. Misenar says, “While the EV fluid exhibited the best wettability on the ball’s surface due to its lowest contact angle, the other test lubricants showed similar contact angle values. However, their levitation behavior at high speeds differed significantly. The highest viscosity 75W-140 oil formed the thickest entrained air film compared to the other two oils.”

The interaction of the three lubricants near the ball surface in the presence of entrained air leads to a stretching phenomenon along the direction of motion. A fluid’s resistance to flow in this manner is known as extensional viscosity. Arya says, “We examined the extensional viscosity of the three fluids through another experimental set-up developed on a computerized numerical control (CNC) machine. An oil drop was placed between two cylinders where the higher one was held in the CNC mill. When the upper cylinder was raised at a constant velocity of 2,750 millimeters per minute relative to the bottom cylinder, the time until the oil film ruptured was measured. The highest viscosity oil, 75W-140, exhibited the longest time to rupture which is an indication of its highest extensional viscosity and the reason it displayed the longest contact stretch near the ball.”

When the diamond-like carbon (DLC) and oleophobic coatings are applied to the ball, the results do not change. The ALE is the dominant phenomenon at high-speed affecting the ability of the three lubricants from adhering to the ball’s surface.

Similar trends were observed with the inner and outer raceways; however, the difference in curvature of the bearing components affected the stability of the levitating oil droplet.

Figure 2 demonstrates how the ALE impacts the shape and appearance of an oil droplet levitating on an air film near a high-speed rotating surface. Arya notes, “The deformation of the oil droplet is analogous to a shape characteristic of a solid body deformation in the elastohydrodynamic lubrication regime.” This observation motivated Arya and Sadeghi to develop a numerical model to simulate the phenomenon and predict droplet deformation resulting from ALE.

Figure 2. A levitating oil droplet due to the ALE is near a ball rotating at 24,000 RPM. Figure courtesy of Purdue University.

Figure 2. A levitating oil droplet due to the ALE is near a ball rotating at 24,000 RPM. Figure courtesy of Purdue University.

Future work will focus on using the test rig to evaluate lubrication effects and frictional losses with the ball, inner and outer raceways in a realistic bearing configuration. Misenar says, “We also intend to examine different ball materials, cage materials and cage geometries.”

Additional information can be found in a recently published experimental paper,

3 and a numerical paper that presents a model for the ALE.4 For additional inquiries, readers may contact Professor Sadeghi at

sadeghi@purdue.edu.

REFERENCES

1.

Canter, N. (2022), “Ice: A more effective heat transfer agent,” TLT,

78 (5), pp. 22-23. Available at

www.stle.org/files/TLTArchives/2022/05_May/Tech_Beat_II.aspx.

2.

Prahl, J., and Hamrock, B., (1985), “Mechanics of a Gaseous Film Barrier to Lubricant Wetting of Elastohydrodynamically Lubricated Conjunctions,” Report No. NASA-TP-2500,

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19850024017.

3.

Arya, U., Misenar, J., and Sadeghi, F. (2025), “Lubricant levitation in high-speed bearings: An experimental approach.”

Physics of Fluids, 37, 047140.

4.

Arya, U., Sadeghi, F., and Meinel, A. (2025), “Modeling of Aerodynamic Leidenfrost effect of Oil Droplets,”

Journal of Tribology, 147 (11), 114601.