Problems with friction on Mars

R. David Whitby | TLT Worldwide May 2021

The InSight mission uncovers an unexpected tribological challenge to exploring the composition of the red planet.

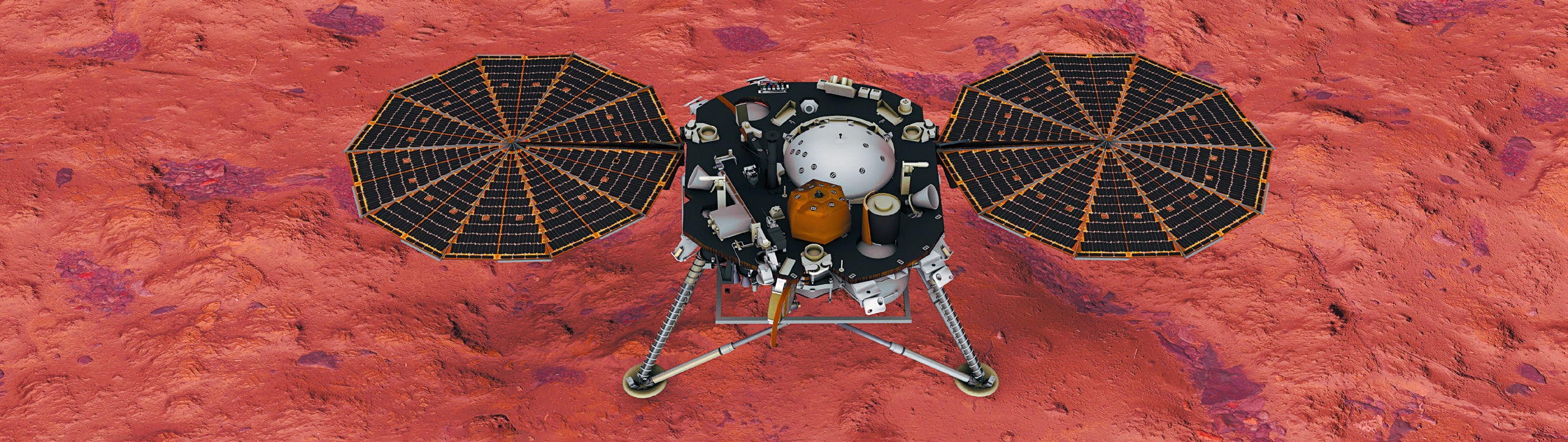

Since Feb. 28, 2019, a heat probe developed and built by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and deployed on Mars by NASA’s InSight lander has been attempting to dig into the Martian surface to take the planet’s internal temperature. The aim was to gather information about the interior heat engine that has driven Mars’ evolution and geology.

The InSight lander touched down toward the end of 2018. The probe was supposed to burrow deeper on Mars than any other machine in history. When the mission left Earth, the team had anticipated that the tip of the probe would reach a depth of about 16 feet (5 meters) below the surface. However, the team could never get it to work.

The InSight mission’s instruments were designed to investigate Mars’ history and the forces that shape rocky planets. In particular, the probe (often referred to as the mole) was meant to hammer itself into the ground, trailed by a tether embedded with sensors. InSight’s landing site was chosen using the standard smooth, flat and boring criteria for Mars missions. Rocky sites are not chosen, so robotic landers do not start the mission by tipping over. Geologists scrutinized observations from orbiting spacecraft and other Mars missions and settled on a location they thought would have soil as fine as grains of sand on a beach.

When the probe started hammering in winter 2019, the team gathered at NASA’s mission control in California to await a message from Mars. They anticipated that the mole would have traveled some distance underground. When the results arrived, the measured distance was zero.

Initial thoughts were that the mole had hit a rock or was damaged. The team commanded the probe to keep trying, checking after each round of several thousand hammer strokes. The first few months of troubleshooting were anxious, because any number of things might have gone wrong.

After months of investigation, the scientists and engineers concluded that the problem was the soil itself. The team had expected that as the mole hammered and descended, loose soil would collapse around the probe, providing the friction it needed to keep going. But the soil in the chosen location turned out to be sticky, clumping together, and had drawn away from the mole, leaving nothing but space on all sides. Tilman Spohn, the principal investigator for the mole experiment at the German Aerospace Center, explained, “It’s as if you are trying to hammer a nail into a hole in the wall. The nail has no grip.”

Before the mission was sent to Mars, engineers had tested the probe in a variety of soil types. The probe bounced back in some tests with stickier soil, particularly in Mars-like atmospheric conditions, but it worked well in most cases, and there wasn’t enough time to make significant design changes before the mission was launched.

After the initial failure, the team tried to persuade the mole into action with a number of unplanned operations. The rover’s robotic arm scooped soil over the mole and even pushed down on the probe. The mission’s seismometer instrument, designed to detect Marsquakes, monitored the rumbling of the mole’s hammering attempts. The team was encouraged when the mole dug a little deeper and was dejected when it had bounced back.

By autumn 2020, the team had managed to put the mole underground to a depth of about 16 inches (40 centimeters), but the sticky soil was still a problem, and the robotic arm couldn’t help any more.

In December 2020, commands for one final effort in January were programmed and beamed toward Mars. After the probe conducted 500 additional hammer strokes on Jan. 9, 2021, with no progress, the team called an end to their efforts. The soil’s unexpected tendency to clump deprived the probe of the friction it needed to hammer itself to a sufficient depth.

However, NASA believes the mission has been a partial success. Unanticipated discoveries have been made about the Martian landscape and geology. Scientists think that the soil contains some salts that are behaving like cement. This kind of regolith has been found on Mars before but wasn’t expected at the In-Sight location, and no one had tried to dig into it. Although NASA has abandoned the mole, the InSight mission will continue until the end of 2022, recording the vibrations coming from deep within the red planet.

David Whitby is chief executive of Pathmaster Marketing Ltd. in Surrey, England. You can reach him at pathmaster.marketing@yahoo.co.uk.