The path of less resistance

Evan Zabawski | TLT From the Editor July 2020

Tribology makes the news.

Photo courtesy of U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory and Southwest Research Institute.

The U.S. Air Force recently announced that a small design change to their KC-135 Stratotanker fleet could reduce air drag and potentially save about $7 million in fuel per year. Although it is encouraging to see a tribological solution making mainstream news, there is an alternate interpretation of the story.

The narrative should really begin in 1995 when McDonnell Douglas was in the fourth and final phase of the MD-11 Performance Improvement Program aimed at improving the aircraft’s weight, fuel capacity, engine performance and aerodynamics. This phase had a 1.2% drag reduction target; 0.5% was achieved by modifying the flap-hinge fairings and seals, and an additional 0.4% by altering the horizontal elevator bias. Though not the most significant improvement, the most well-known design change was switching the orientation of the windshield wipers’ rest position from horizontal to vertical.

The recent news reported that researchers at the Advanced Power and Technology Office, part of the Air Force Research Laboratory, identified the KC-135 as a candidate for a similar windshield wiper modification in 2019. They partnered with the Southwest Research Institute, the Air National Guard and the Air Force Operational Energy Office to validate the concept and quantify the efficiency gains.

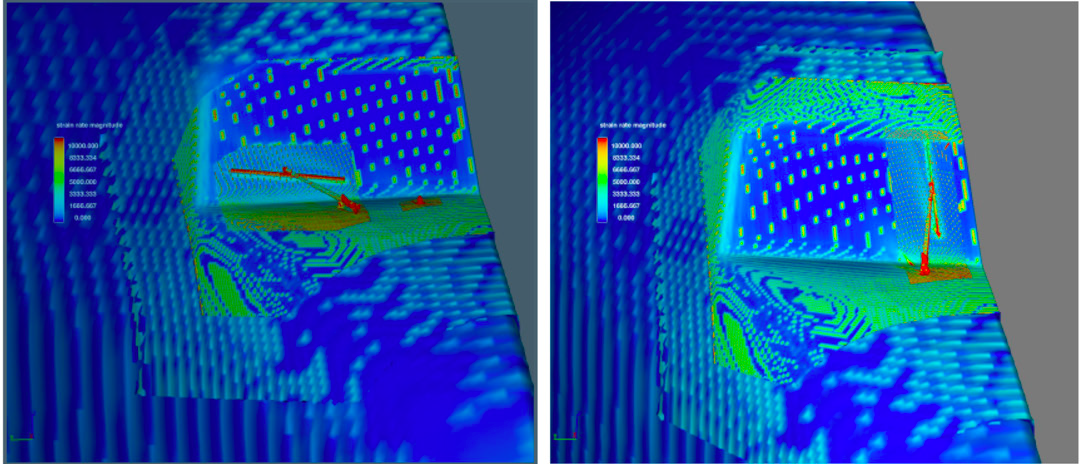

Computation fluid dynamics were used to model air flow simulating cruise conditions with both horizontal and vertical wiper positions (

pictured). The data showed drag was reduced 0.8% with the wiper positioned vertically and reduced another 0.2% with a slimmer wiper design. A 1% total reduction becomes significant given the current fleet of 396 planes, split between the active Air Force, Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard, accounting for 14% of the total Air Force aviation fuel use in 2019, over 260 million gallons.

The Air Force’s news release ended with a statement that another phase of design refinement is planned for this summer, and that the researchers also have partnered with Delta Airlines to assess the possibility of incorporating a vertical wiper on their fleet of 77 Boeing 767 airplanes. It seems intuitive that one airline is inspired by another’s findings, but the question is why was neither equally inspired when the MD-11 altered its wiper design 25 years earlier? At that time, there were still about 600 KC-135 in use. Just imagine how much fuel would have been saved had the design change been made then.

It has often been said that the seven most expensive or dangerous words in business are: “We have always done it this way.” The initial horizontal wiper orientation on airplanes was undoubtedly inspired by contemporary automobiles, which, in turn, was based on limiting the amount of visual impairment from a pair of synchronous wipers resting on a single windshield. Modern automobiles continue to position wipers horizontally so they can be recessed into a wiper cowl for optimum aerodynamics and minimal visual obstruction. However, airplane windshields are composed of several separate panels, with a single wiper per primary panel, and are not designed with wiper cowls.

Simply put, there is no reason a wiper needs to rest horizontally on an airplane other than we have always done it that way. Fostering culture change to encourage the questioning and updating of ageold designs can be difficult, but questioning something is a form of learning since the answer should reveal the advantages and disadvantages of the current design over any alternative. If no alternative exists other than “we have always done it this way,” then there might be an opportunity for improvement.

In fairness, many newer aircrafts have vertical wipers, but it seems like a lost opportunity to not have assessed similar modifications on other fleets once the advantage was initially identified.

Evan Zabawski, CLS, is the senior technical advisor for TestOil in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. You can reach him at ezabawski@testoil.com.