Spitball science

Evan Zabawski | TLT From the Editor October 2019

Putting something on the ball.

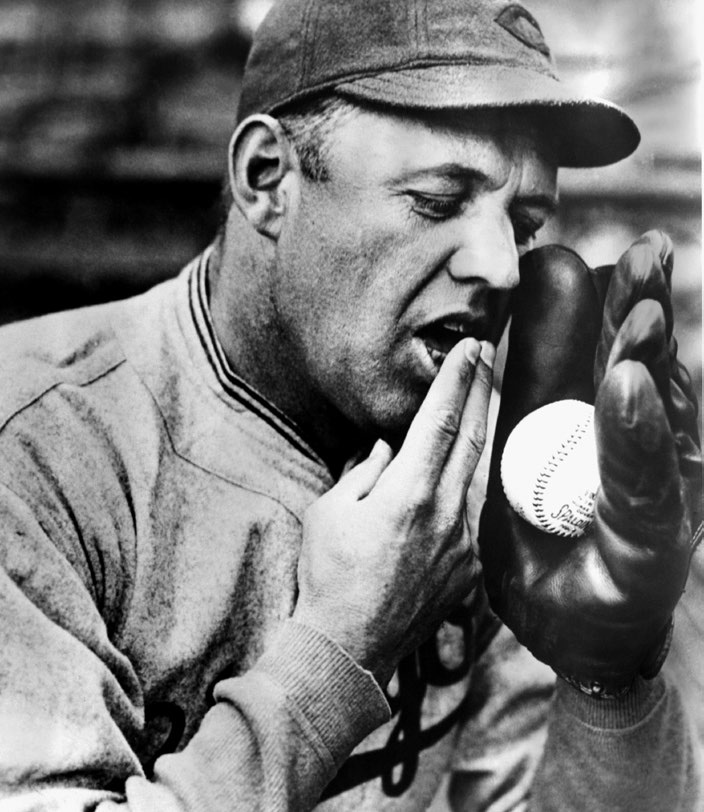

Brooklyn Dodger Burleigh Grimes threw Major League Baseball’s last legal spitball on Sept. 20, 1934.

Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

One of the greatest changes to the rules of Major League Baseball dealt with friction—specifically altering the friction characteristics of the ball. On Oct. 30, 1919, the American and National League presidents demanded that the spitball be abolished, yet its use lingered legally and illegally for decades.

A spitball is a pitch using a ball that has been altered by a scuff, cut or foreign substance (like spit). The Magnus effect describes how a ball pitched with backspin creates lift, topspin forces it to drop, and sidespin causes lateral curving. A spitball will move less in the expected direction because lubrication between the ball and fingers will inhibit the spin of the ball.

The first documented occurrence of a pitcher moistening the ball prior to pitching describes an 1868 double header between the Eckfords and the Lord Baltimores. Baltimores pitcher Bobby Mathews was observed rubbing the ball with his hands so that one side remained white and the other became wet; the resulting pitches curved wildly. Over the next 50 years the concept became so popular every manner of a lubricant was being applied to balls, including tobacco juice spittle, Vaseline or sunscreen, while some pitchers even tried tacky substances like pine tar or rosin to obtain a better grip and impart more spin.

The National League was the first league to approve the banning of spitballs on Dec. 10, 1919, largely due to the efforts of Pittsburgh Pirates owner and eventual Hall of Famer Barney Dreyfuss. Sadly, the American League was slower to adopt the same rules, resulting in tragedy when the New York Yankees hosted the Cleveland Indians on Aug. 16, 1920.

That day had intermittent fog as the Indians’ Ray Chapman led off the fifth inning against the Yankees’ Carl Mays. The first pitch, a spitball, struck Chapman on the left side of his head, dropping Chapman to the ground. Although he managed to get to his feet and walk toward the clubhouse, Chapman lost consciousness and had to be carried the rest of the way. He was taken to St. Lawrence Hospital and around midnight doctors operated on a three-inch fracture. Though he survived the surgery, Chapman died before his wife arrived a few hours later. Chapman is the only major league player to die from injuries during play.

For the 1920 season both leagues adhered to a new ruling, namely 6.02(c), which says a pitcher cannot: (1.) touch the ball after touching his mouth or lips, (2.) spit on the ball or his glove, (3.) rub the ball on his glove, person or clothing, (4.) apply a foreign substance to the ball, (5.) deface the ball, (6.) “deliver a ball altered in a manner prescribed by Rule 6.02(c) (2.) through (5.) or what is called the ‘shine’ ball,’ ‘spit’ ball, ‘mud’ ball or emery ball. The pitcher is allowed to rub the ball between his bare hands” or (7.) have a foreign substance on his person or in his possession. The penalty is immediate ejection and a 10-game suspension.

In preparation for the ruling, each “major league club was asked to submit the names of current spitballers whose use of the pitch would still be allowed.” This grandfathering allowed 17 pitchers to continue pitching spitballs for many years. Brooklyn Dodger Burleigh Grimes holds the distinction of throwing the last legal spitball (spit from chewing elm bark) on Sept. 20, 1934—14 years after the rule came into effect.

Gaylord Perry pitched for eight different teams from 1962 to 1983 and literally wrote the book on illegal spitballs in 1974 called Me and the Spitter. Despite his brazen flaunting of the rules, Perry was only ejected once in his career, during his 21st season on Aug. 23, 1982, but simply for being on the mound when a scuffed ball was in play, not for throwing a spitball.

The two most recent ejections in Major League Baseball occurred early in the 2015 season for pitchers using rosin or rosin mixed with sunscreen. Perhaps spitballs have finally faded from existence, given all the high-definition cameras now watching pitchers from every angle in a bid to prevent such antics.

Evan Zabawski, CLS, is the senior technical advisor for TestOil in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. You can reach him at ezabawski@testoil.com.