The 3,000-mile myth

Evan Zabawski | TLT From the Editor February 2019

Old habits die hard, but this one is apparently immortal.

3,000 miles was already phased out as an OEM-recommended oil change interval when this 1969 Pontiac Firebird was new.

Photo courtesy of CarGurus, Inc.

This is not the first article on the subject of the habit of changing engine oil too frequently, but I wish it could be the last. It is rather remarkable how resilient this habit is, despite technological improvements to both engines and lubricants. Harvard economist Henry Rosovsky once said, “Never underestimate the difficulty of changing false beliefs by fact,” referring to the bias toward a desired interpretation, and this may be a perfect example.

The most common reasons given for changing oil at a very low mileage are:

1.) Oil degrades or breaks down.

2.) Additives wear out.

3.) Oil should always be changed at 3,000 miles.

4.) It’s cheap insurance.

Oil degrades/additives wear out

It is true, oil does break down and additives do wear out but

slowly. Degradation and additive depletion will not reach significant levels within a typical drain interval under normal driving conditions, but both will occur faster under severe driving conditions. Even so, mileage alone cannot be the primary indicator; engine revolutions and temperature are better indicators.

Among the most compelling research to illustrate this point comes from papers published by the late Dr. Shirley Schwartz (former STLE member) and STLE-member Dr. Don Smolenski from General Motors Research as they developed the Oil Life Monitor (OLM). During their trials, which began in the 1980s, they accumulated 100,000 miles on vehicles under all conditions while monitoring acid number, base number, differential scanning colorimetry (for remaining life of the antioxidant) and pentane insolubles.

The research showed that, given the engine and oil combinations at the time, the oil could be run 10,000 to 12,000 miles before significant degradation byproducts accumulated and additives depleted to levels requiring replenishment from an oil change. One factor that showed greater influence than simply distance was temperature, displaying an almost parabolic Goldilocks relationship where a bulk oil temperature that is too hot or too cold increases the aging rate.

Lubricant manufacturers have performed other studies with oil drains up to 60,000 miles, typically involving fleet vehicles like taxicabs, proving their oils can stay in service without significant breakdown or additive depletion with no increase in wear. The main qualifier to these long drain intervals is filtration, namely the use of bypass filtration systems, and this matters as the primary reason oil needs to be changed is contamination, mostly from combustion in the form of acidic byproducts, as well as particulate from air and the fuel itself.

The second qualifier is the use of fleets to perform these studies. While there is an advantage in providing a higher density of data points, such fleets exclude a common variable driving the oil change interval: short trips. A short trip is not simply a short distance of travel; it also refers to having a cold-start. Cold-starts force excess fuel into the oil, but longer trips drive off this fuel (and water from humidity or combustion).

Short trips are far more common in passenger vehicles than in fleet vehicles, resulting in more contamination, which is why many oil drain intervals have included a time factor (“every 3,000 miles or three months, whichever comes first”). The supposition is that lower mileage in a set period is a result of driving mostly short trips, but this has led some to the false belief that oil has a finite life.

Some manufacturers have qualified their statements in more detail such as, “Change oil each 6,000 miles. IMPORTANT: In certain types of service, including operation under dusty conditions, trailer hauling, extensive idling or short trip (engine not thoroughly warmed up) operation at freezing temperatures, THE OIL CHANGE INTERVALS SHOULD NOT EXCEED TWO MONTHS, OR 3,000 MILES.” The wording refers to particulate contamination (dusty), high temperatures (trailer hauling), excess fuel contamination (idling) and low temperatures (short trips), reaffirming that driving habits, which influence temperature or contamination, are the primary factors in determining the oil drain interval, not simply time or distance. But this is not a recent revelation; that text is from a 1969 Pontiac manual.

However, considering that air filtration has greatly improved and combustion characteristics are monitored much more closely, oils should be cleaner than ever, right? Almost. Ever-changing emissions guidelines have driven engine manufacturers to implement design changes like positive crankcase ventilation and exhaust gas recirculation, therefore engine oils are exposed to more and more of such contaminants as engine design evolves, and lubricant manufacturers are continually improving their products to meet these requirements.

It was best said, “Oils have been greatly improved, driving conditions have changed and improvements in engines, such as the crankcase ventilation system, have greatly lengthened the life of good lubricating oils. However, to ensure continuation of best performance, low maintenance cost and long engine life, it is necessary to change the crankcase oil whenever it becomes contaminated.” That text appears in a 1938 Chevrolet manual, which also recommends “

draining the crankcase and replacing with fresh oil every 2,000 to 3,000 miles” unless “driving over dusty roads,” “short runs,” etc., proving this was not a revelation in the 1960s either.

Contamination and operating temperature are what are really driving the oil drain interval, although oil degradation and additive depletion are effects that take much longer than 3,000 miles to manifest. Careful monitoring of known, correlating factors has allowed OLM technology to derive the oil drain interval more intelligently than simply defining “normal” and “severe” driving conditions, each with its own mileage/time limit. Due to implementation of the OLM, GM increased its recommended oil drain interval to up to 7,500 miles in the late 1990s, and 10,000-15,000 miles in the early 2000s.

3,000 miles—since when?

While not everyone believes that 3,000 miles is the current recommended interval or best practice, it is not uncommon to hear statements like, “Twenty-five years ago, the common oil change recommendation was typically every three months or 3,000 miles” or “From a starting base of about 3,000 miles in the early 1990s… .” Unless these statements are referring to severe conditions, they are off by decades.

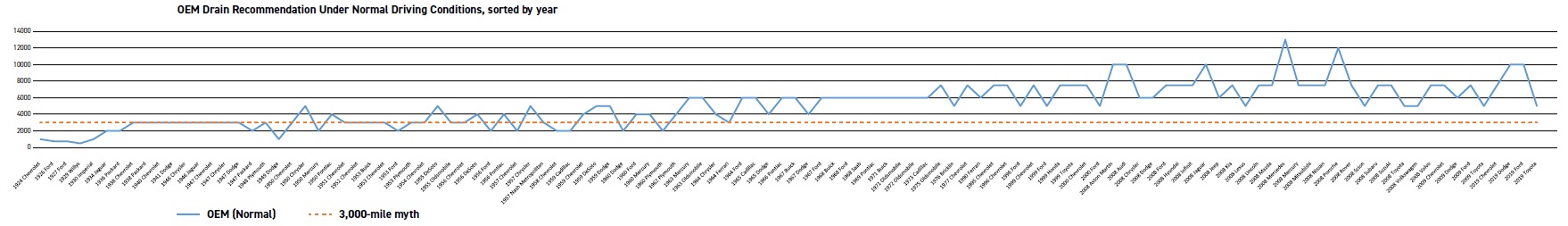

Note: The drain intervals in the below graph were obtained directly after poring over 95 years’ worth of online car manuals and taken from the recommendation under normal driving conditions and during summer months (if applicable) for gasoline-powered vehicles only. Manuals from the last 20 years, though more easily obtainable, often neglect to list a mileage recommendation and defer to the OLM technology.

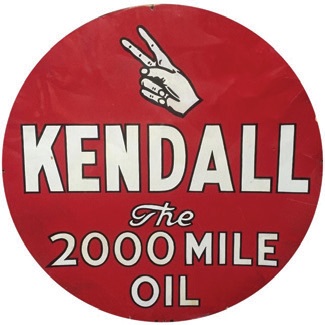

Starting with a 1924 Chevrolet (1,000 miles), 1926 and 1927 Ford Model T (750 miles), 1929 Willys Whippet Four (500 miles) and a 1930 Imperial 8 (1,000 miles), drain intervals routinely fell between 500 and 1,000 miles. However, in 1928 this began to shift when the Kendall Refining Co. introduced the first “long mileage” oil with its “2,000 mile oil” (hence their iconic two-fingered logo) (

see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Kendall Refining Co.’s iconic two-fingered logo.

Figure 1. Kendall Refining Co.’s iconic two-fingered logo.

Through the 1930s, 2,000-mile intervals (1934 Jaguar SS, 1936 Packard 8) transitioned to 3,000 miles (1938 Chevrolet and Packard) and became the norm through the 1940s with two exceptions. By the 1950s the drain interval varied from 2,000 to 5,000 miles. About this time another event initiated a change—the publishing of Dr. Arie Jan Haagen-Smit’s paper on Los Angeles smog in 1952.

In 1958 GM Research concluded engine design to be a major contributor to smog and offered its Positive Crankcase Ventilation (PCV) technology royalty-free to other U.S. automotive manufacturers as the solution. At first it was only installed voluntarily on cars sold in California until a 1965 amendment to the Clean Air Act made it mandatory on all 1968 model year vehicles.

Implementation of PCV technology forced changes to engine design and lubricant formulation, predominantly base oil quality, as well as a revision to the engine test for deposit formation. Results from the newer Sequence VC engine test proved high-quality oils would prevent fouling of the PCV valve, thereby helping to further extend drain intervals.

Through the 1960s the average recommended drain interval climbed from 4,000 miles to 6,000 miles; thus, the departure from 3,000 miles as a commonly recommended drain interval was 50 years ago. To say the 3,000-mile habit was handed down to us from our fathers must be expanded to say that even they must have learned it from their fathers, possibly even one more generation further back. However, this is not your grandfather’s oil anymore. But I digress.

Given some of the major technological innovations over the last 50 years, like the personal computer, cell phones, the Internet and GPS, and then the subsequent merging of these devices into smart phones that outnumbers cars 2:1, it is perplexing to think that engines and oils have not also improved significantly in the last 50 years.

The first 7,500-mile recommendations (1975 Oldsmobile and 1977 Chevelle) arrived in the 1970s. This decade also brought about further amendments to the Clean Air Act, resulting in changes and additions to engine hardware. One addition affecting the oil was exhaust gas recirculation, which consequently threatened the drain interval. However, the removal of lead from gasoline, beginning in 1975, helped offset this factor.

In the 1980s and 1990s, oil drain intervals bounced between 5,000 miles and 7,500 miles, influenced in part by the introduction of on-board diagnostics (OBD) in 1991 and improved air filtration technology. OBD monitors emission-related systems to fine tune the combustion process, resulting in cleaner combustion and emissions.

By the 2000s the range broadened from 5,000 miles to 15,000 miles. While some are quick to credit the wider use of synthetic fluids, some manuals merely stated, “You may use a synthetic motor oil if it meets the same requirements given for a conventional motor oil: it displays the API certification seal, and it is the proper weight. You must follow the oil and filter change intervals shown on the information display.” This reinforces the fact that though synthetic fluids may degrade more slowly than conventional oils, the drain interval is still largely driven by contamination, which affects synthetic oils nearly equally as conventional oils.

It is simply not true that 3,000 miles was the OEM recommended interval any time recently. Some of the manuals that defer to OLM technology state, “If the engine oil life system is ever reset accidentally, you must service your vehicle within 3,000 miles since your last service.” Perhaps this is where the thinking originates?

Through the 1960s the average recommended drain interval climbed from 4,000 miles to 6,000 miles.

Through the 1960s the average recommended drain interval climbed from 4,000 miles to 6,000 miles.

© Can Stock Photo / ronstik

Cheap insurance

I will admit I have stated that oil changes are cheap insurance, but I use it in the context of why I follow the OEM recommended interval in my vehicles, both under warranty and beyond, even though I strongly believe I could safely double it. However, in the context of a 3,000-mile oil drain being cheap insurance, it is a weak argument if the other forms of cheap insurance are not also being performed (i.e., daily oil level checks, belt and tire inspections, etc.).

This mantra seems to have been perpetuated by oil marketers and the quick lube service stations. I recall reading an article about 15 years ago where two CEOs of different quick lube chains were asked point-blank why their companies still pushed the 3,000-mile interval when manuals clearly stated a much longer recommended interval; one CEO answered honestly that it would cost his company millions in profits.

In 2010 The New York Times reported that Jiffy Lube, the largest quick oil change company in North America, succumbed to pressure and piloted a program whereby the technician would inform the customer of the OEM recommendation for both normal and severe conditions, and that it would roll out this program completely in 2011.

However, Jiffy Lube also claimed that 92% of motorists drove under these so-called severe conditions and could therefore continue to push the 3,000-mile interval so long as it was listed in the manual. Former Jiffy Lube CEO Stu Crum said that 47% of their customers opt for the severe condition recommendation, with plans to have their oil changed an average of every 3,502 miles.

But what happens when the manual defers to OLM technology and does not list any mileage? Some quick lube operators believe that going beyond 5,000 miles is asking for trouble, and even Pat Wirth, president of the 1,200-member Automotive Oil Change Association, says dashboard warning lights can provide “a false sense of security” because they aren’t necessarily accurate.

Some oil marketers have actually gone in the opposite direction and touted the longevity of their products. There have been 5,000-mile, 10,000-mile, 15,000-mile, 20,000-mile and even 25,000-mile guarantees right on the front label of branded oil bottles. These are not even a recent convention; one of the first 25,000-mile guarantees appeared on another Kendall Motor Oil product in 1963 (

see Figure 2).

Figure 2. 1963 ad for Kendall’s 25,000-mile oil, showing progression of drain intervals and the term ‘long mileage.’

Figure 2. 1963 ad for Kendall’s 25,000-mile oil, showing progression of drain intervals and the term ‘long mileage.’

It has been so difficult fighting quick lube stations that the government had to intervene in California with Senate Bill SB-778 (Allen). Section 1(b) states, “Oil quality and engine technology have evolved significantly in recent years. New motor oil formulations reduce repairs, prolong engine life, improve fuel economy and enable significantly longer oil change intervals than outdated 3,000-mile-oil-change marketing campaigns.”

The bill acknowledges severe driving conditions but also refers to the waste of oil (one of their largest waste streams at 115 million gallons sold, with only 70% of the used oil being collected) and money. Section 1(e) states, “It is the intent of the Legislature to ensure that the oil drain interval recommended by an automotive repair dealer or an automotive maintenance provider be in accordance with the vehicle manufacturer’s published maintenance schedule in order to prevent deceiving or misleading consumers with unnecessary and costly oil changes.”

The economic justification is not simply comparing the cost of the oil change to the cost of replacing the engine; as SB-778 points out there is a needless waste of resources and money. The justification should be that in a typical 100,000-mile warranty period, a 3,000 mile drain interval calls for more than 20 extra oil changes compared to a 10,000-mile OEM-recommended interval. At a minimum of $30-$80 for an oil change service, that is a significant savings to the driver that will not affect the engine, its performance or warranty, and would divert a minimum of 20 gallons of used oil (per vehicle) from the waste stream.

Vested interest

Interestingly, the aforementioned 1969 Pontiac manual indicated the same vehicle came with a warranty period that was only 12 months or 12,000 miles, except for the drivetrain, which was warrantied for five years or 50,000 miles—whichever comes first, of course. Today’s vehicles still come with a comparable drivetrain warranty, and although some are up to 100,000 miles (or more) they are still typically limited to five years, but they have overall warranties that are a least triple the time and mileage.

When the OEM is providing longer warranties, it seems implausible that oil drain intervals have not also increased. Accordingly, service schedules have increasingly longer intervals, therefore the absence of any need to check anything else on the vehicle within 3,000 miles negates the argument that an oil change is like a routine dental checkup (would you get your teeth cleaned every three months if the dentist wanted to check them every six months?).

Lubricant manufacturers have moved from API Group I/II base oils to Group II/III/IV, which are better able to handle extreme temperatures and resist some degradation. Additive manufacturers have created more robust additive packages with improvements like greater dispersancy to handle particulate contamination and improved antiwear to prolong the life of the engine, meeting the latest API certification for OEM warranty compliance. The combination simply equates to longer lasting engine oil.

When OEMs, lubricant manufacturers and additive companies have all participated in studies to show their engines don’t wear significantly, their lubricants don’t degrade quickly and their additives handle both sides (even for the full warranty period without needing to be changed), who stands to benefit from a continued practice of changing oil every 3,000 miles?

If a dealer contradicts an OEM, or a quick lube station contradicts the lubricant manufacturer, who do you believe? Like the idiom says, “When all else fails, read the manual.”

Evan Zabawski, CLS, is the senior technical advisor for TestOil in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. You can reach him at ezabawski@testoil.com.