Life at the leading edge

Dr. Robert M. Gresham, Contributing Editor | TLT Lubrication Fundamentals January 2019

STLE's 2018 Tribology Frontiers Conference focused on the link between innovation and application.

STLE’s research community presented the kind of diverse and leading-edge work that surprises and amazes us.

© Can Stock Photo / artjazz

As you might guess from the headline, I attended the 2018 STLE Tribology Frontiers Conference in Chicago last October and have some thoughts. (Now’s the time to turn the page if you are not interested.) First, however, it is worthy to note that the conference continues to be successful and especially supports our academic and advanced research community. Further, this conference has strong international interest as the attendance included 45% from 24 different countries beyond the U.S. This is all pretty consistent with the goals of the conference over the years, which is good to see.

One further goal is for the technical content to be as leading edge as possible—at the frontier. Historically, at least in my time, the content mainly centered on learning what happens to metal mating surfaces during operation of equipment through the various phases of the Stribeck curve in a wide variety of environments. Years ago this began with human visual observations of wear patterns. Over time we have learned to make these observations with evermore magnification and analytical prowess to discern the tribochemical interactions that take place when, first, macrosurfaces, then asperities, then intended or unintended surface coatings on the asperities, come into contact.

Now through such gadgets as atomic force microscopes and the ability to perform molecular simulations, we are trying to look at what happens to the first few atoms from each surface when they come into contact—but with the challenge of relating this information back to the macroscale. Not yet a done deal. One example in the recent conference was the large number of papers studying the early formation of white etching cracking in bearings as they begin to fail. The 10-ton gorilla problem is the premature failure major bearing systems in wind turbines. Yep, studying these atomistic processes is pretty leading edge.

Another change that began a few years ago has been the shift to study evermore diverse topics where tribological interactions play a key role, both good and bad. Initially I thought this was just a clever way to get research funding, which at least in the U.S. has been tight, if not downright difficult to get. Maybe so, but the end result is these advances have led to some pretty good innovations affecting society beyond the vast improvements already seen in reliability and efficiency, with corresponding emission reductions in transportation and industrial machinery.

At the recent conference we saw startling examples of these diverse, leading edge, on-the-frontier topics. In a plenary session, we heard Dr. Greg Sawyer from the University of Florida discuss his group’s work in elucidating some of the tribological complexities associated with the emerging field of biomedicine as living tissues contact either other tissues or surfaces. In his case, it was the friction of corneal epithelial cells protecting the eye. This could lead to improved, longer-lasting, less-irritating contact lenses or improved eye-injury management.

© Can Stock Photo / duskbabe

We heard a plenary session by Dr. Stanislav Gorb from the University of Kiel. Previously he had talked on how geckos and insects cling to walls and ceilings using tribologically related adaptation to enable these seeming gravity-defying miracles. At the conference he discussed how terrestrial snakes have adapted their skins to enable faster, more energy-efficient movement. The key here is how to improve the design and performance of textured surfaces for humans.

© Can Stock Photo / Saaaaa

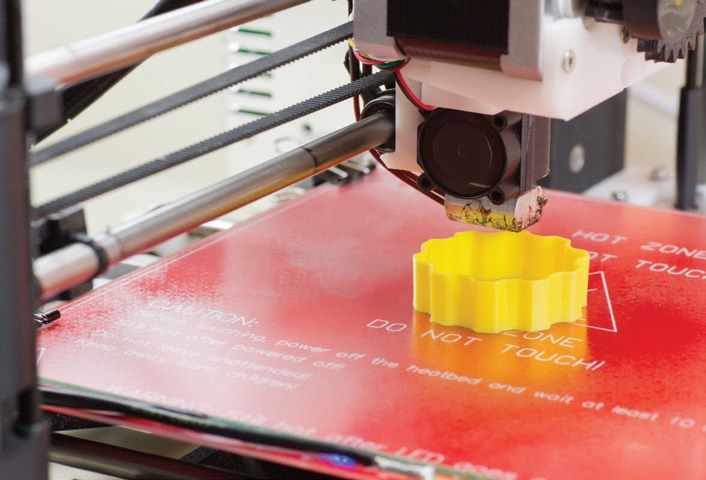

While seemingly not so directly relevant to tribology, yet still leading edge, was a fascinating plenary talk on 3D printing by Dr. Nicole Zander, U.S. Army Research Laboratory. Her goal, at or near battlefields, was to recycle various plastics, metals and paper via 3D printing to replace worn parts, even if temporarily. The captivating concern is that some of these parts might be used in assemblies that perform mechanical operations with tribological implications. Will 3D printed parts, whether from recycled materials as in her example, or from OEM 3D printing (additive) manufacture, present us with new surface morphologies with tribology problems to solve?

© Can Stock Photo / hopsalka

Additionally, in the technical sessions, there were several talks on the tribology of various engineering plastics. Here pressure-velocity performance is key. As you increase load or speed, aside from ambient temperature effects, the internal temperature of the plastic increases. As this happens, the plastic can soften or deform as it approaches its glass transition temperature (Tg). Thus, it is important to know and understand the inherent properties of the engineering plastic and mesh this with the operational parameters of the application. These plastics—often with complicated chemical names and acronyms like PEEK, UHMWPE, etc.—offer light weight, mold or cast-to-weight, rapid construction with minimal waste for certain tribological or structural applications.

There were other talks on such diverse topics as to how mosquitos can pierce the skin painlessly. Could there be medical device applications here? Or a talk on rubber/ice friction mechanisms with obvious application to driving cars on ice. Or a talk on fingertip friction/tribology of Braille and neural correlations. Could this lead to some kind of enhanced use of the tactile abilities of our fingertips for both sighted and sightless people? But the talk that really caught my eye was on the friction of fault lines leading to earthquakes. Often we can identify fault lines in nature; could we learn to “lubricate” these fault lines so the plates can slide incrementally without the life-threatening and devastating effects of a large tectonic shift? That’s quite literally leading edge.

© Can Stock Photo / Naypong

At such a conference you can’t attend every presentation, but these are certainly examples of the very diverse and leading-edge work of our research community that continually surprise and amaze us. While the STLE Tribology Frontiers Conference is surely important to the research community, providing a venue to showcase their work and interact with their peers, it also provides awesome technical entertainment observing mankind’s ability to explore and develop a cognitive perspective of mankind’s environment.

Bob Gresham is STLE’s director of professional development. You can reach him at rgresham@stle.org.