Copper-bottomed guarantee

Evan Zabawski | TLT From the Editor October 2016

An idiom with ties to friction reduction.

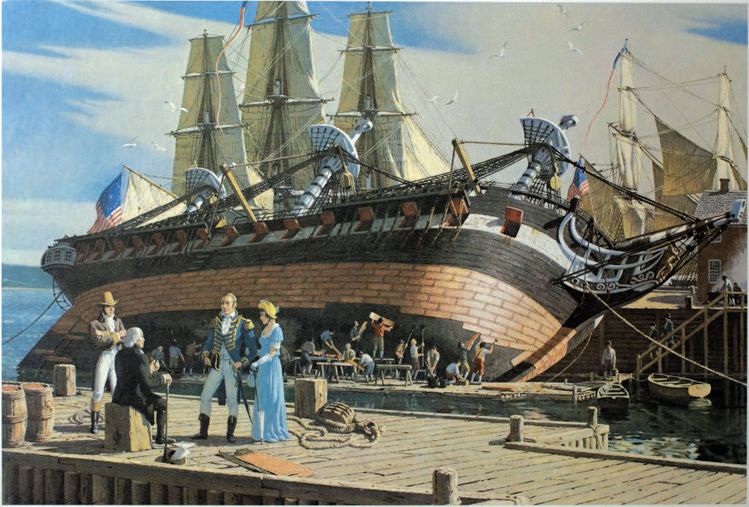

Describing a ship as both copper-bottomed and copper-fastened was a compliment of the highest order and indicated she was properly equipped.

Photo courtesy of Paul Revere Life Insurance Co. / USS Constitution Museum Collection 282.2a.

A COPPER-BOTTOMED GUARANTEE is one of the highest caliber; however, the term copper-bottomed often conjures images of cookware rather than its actual reference to wooden sailing ships. The origin of the term relates to efforts to extend hull life, which indirectly decreased friction yielding faster ships.

Before the 19th Century ship hulls were typically constructed of white oak, and their greatest natural foe was the teredo worm. The teredo worm earned its nickname ‘shipworm’ due to its resemblance to a worm and its proclivity to bore through hulls, but in actuality it is a bivalve mollusk with familial ties to clams. Other underwater adversaries are weeds and barnacles, which attach to hulls in such great numbers as to noticeably affect their speed.

A common method for dealing with shipworms was to employ a layer of thin, expendable wood sheathing. This non-structural layer could easily be replaced in dry dock, but it offered no protection from barnacles and other marine growth. The ancient Romans had used lead sheathing, but this practice was forgotten during the middle ages until it returned briefly during the early 16th Century in Spain and again in the 17th Century in England. It was abandoned after it was discovered the lead would corrode rudder-irons faster than wooden-sheathed or even non-sheathed ships.

In 1708 Charles Perry proposed copper sheathing, but it was rejected as it was viewed as both cost prohibitive and high maintenance. In 1759 the Royal Navy experimented by copper sheathing the false keel of the HMS Invincible and then fully sheathing the HMS Alarm in 1761. When the Alarm returned to England after two years of sailing in the West Indies it was observed to be free from fouling and worm damage.

The success was short-lived, for it was discovered that the copper bolts used to attach the sheathing reacted with the iron bolts used on the hull, and the Alarm’s copper was removed completely in 1766. The fact that two dissimilar metals in seawater would form a galvanic cell where the most oxydizable metal, in this case iron, would corrode rapidly was not known at the time. Woe be the mariner who used iron nails to attach the copper sheets; they would see the nails corrode and the sheets lost.

The Royal Navy decided to copper sheath its entire fleet during the American Revolutionary War, which allowed their ships to stay at sea longer without the need for cleaning or repairs. The ships’ increased speed and maneuverability were also noted, and as they also entered war with France, Spain and the Netherlands, any and all advantages were exploited, even if at the expense of corroded hull bolts.

A paper published in 1900 described just how beneficial copper sheathing was to sailing by listing the coefficient of resistance for various materials. A smooth sawn plank yielded a coefficient of 0.016, whereas clean copper was 0.007. For perspective, iron skin was 0.014 and would drop to 0.010 with smooth paint, and a moderately fouled surface would be 0.019 and barnacled would be 0.065.

Once a suitable copper/zinc alloy was developed for hull bolts in December 1783, the Royal Navy began re-bolting all ships and putting an end to corrosion problems, though it would take until August 1786 to complete. Therefore, describing a ship as both copper-bottomed and copper-fastened was a compliment of the highest order and indicated she was properly equipped and built to last. This is attested by the USS Constitution, launched in 1797, which remains afloat in Boston, Massachusetts; although it has been re-coppered at least 12 times since the first refit in 1803 when Paul Revere provided the copper sheets.

These once literal expressions have now become figurative expressions; the Oxford English Dictionary defines copper-bottomed as “thoroughly reliable; certain not to fail.” Copper-fastened is defined differently by the Dictionary of Newfoundland English of 1980 as “to reach a clear and firm understanding or agreement without loop-holes or ambiguity.” Alas, the friction reducing aspect never gained traction!

Evan Zabawski, CLS, is the senior technical advisor for TestOil in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. You can reach him at ezabawski@testoil.com.