The challenge of bringing synthetic lubricants to market

Debbie Sniderman, Contributing Editor | TLT Feature Article February 2016

Performance, price and product differentiation are keys to entry, but acceptance still can take years.

The marine market is just one area where new synthetic base fluids from renewable feed stocks are needed.

© nightman1965/iStock/Thinkstock

KEY CONCEPTS

•

Due to emerging regulations and more demanding applications, new lubricant products always generate curiosity.

•

Most synthetic lubricant base oils are derived from petrochemical feed stocks.

•

Bringing new lubricant products to market is an expensive proposition and takes years.

LUBRICANTS DERIVED FROM SYNTHETIC BASE FLUIDS, such as the API Group IV and V products, have been manufactured and used for several decades. Some say there has been minimal progress in bringing to market new base fluids during the past many years. For example polyalphaolefins, polyolesters, polyalkylene glycols (PAGs), phosphate esters and polyisobutylenes have been sold for at least 40 years and dominate the synthetic lubricant landscape. Although there is significant innovation ongoing in our industry, some think attempts to bring new synthetic base oil technologies to market need to be better.

Synthetic lubricants solve problems that conventional mineral oils cannot. Like mineral oils, most synthetic lubricant base oils are derived from petrochemical feed stocks. While a small number of esters are derived from renewable feed stocks, the vast majority are derived from petrochemical feed stocks.

Most innovation today in the area of synthetic base fluids is targeted at developing products from renewable feed stocks. This is, in part, driven by environmental policies and a trend toward more sustainable solutions. There are several start-up companies leading such innovation, spending years and tens of millions of dollars developing their technologies. Yet, despite this investment, some industry analysts believe the need for synthetic fluids derived from renewable feed stocks is not evident.

NEED FOR NOVEL SYNTHETIC BASE FLUIDS

According to STLE-member Daryl Beatty, product development manager at American Chemical Technologies (ACT)—a privately owned supplier of lubricants for more than 40 years located in Fowlerville, Mich.—there are many opportunities for new oils that offer new chemistries, and there have been many new innovations offering improvements and new applications for existing chemistries in the last few years. Beatty started and managed his own private label blending company as a start-up and then began working with ACT.

American Chemical Technologies

The drum and tote filling station at ACT where small batch blending also is done. (Photo courtesy of American Chemical Technologies.)

The drum and tote filling station at ACT where small batch blending also is done. (Photo courtesy of American Chemical Technologies.)

The pail station at ACT where the product is metered off from a finished bulk tank and put into pails. (Photo courtesy of American Chemical Technologies.)

The pail station at ACT where the product is metered off from a finished bulk tank and put into pails. (Photo courtesy of American Chemical Technologies.)

The main station where railcars and tanker trucks are offloaded and loaded at ACT and where railcars wait for unloading in the building. The main bulk manifold is used for unloading, loading and blending of products. (Photo courtesy of American Chemical Technologies.)

The main station where railcars and tanker trucks are offloaded and loaded at ACT and where railcars wait for unloading in the building. The main bulk manifold is used for unloading, loading and blending of products. (Photo courtesy of American Chemical Technologies.)

“The increased use of Group III hydrocarbons has come on strong,” says Beatty. “There’s a new line of Oil-Soluble Polyalkylene Glycol (OSP) Base Fluids from Dow, and a new base stock that has shown improvements over traditional polyalphaolefins (PAOs). Alkylated naphthalenes (ANs) aren’t new but have seen a lot of increased usage. What’s driving them is always going to be whether the same thing can be done for less money, or something can be done better for the same money. Cost always factors into it.”

STLE-member Andrew Larson, associate technical service and development manager working in the performance lubricants business for The Dow Chemical Co. in Midland, Mich., says automotive is one industry where performance and regulations are driving the continued development of new synthetic oils. Larson works closely with formulators, OEMs, end-users and Dow’s internal R&D group.

Automotive also might offer the greatest opportunity for synthetics. “Overall, fleets need higher fuel efficiency to meet upcoming government regulations and benchmarks in 2017 and 2025,” says Larson. “The automotive industry is looking for any type of technology that can help them improve the efficiency of cars to reach these benchmarks, and they are spending a lot of money.”

The industrial market is another performance-based space as higher demands are being placed on the gear oils, compressors, hydraulic fluids and turbine fluids. “Customers need higher temperature performance out of their fluids as equipment is getting smaller and processing temperatures are getting hotter,” says Larson. “More demands are made on tighter footprints and the pressure of faster cycle times, stressing the fluids more. So customers are looking for any extra performance fluids that gives them less downtime. The best way to get a new synthetic introduced is by demonstrating less downtime such as a new fluid that can last longer in a system without varnishing or needing to be topped off. There’s always interest in a fluid that can meet these needs and is balanced to be affordable.”

Automotive is one industry where performance and regulations are driving the continued development of new synthetic oils.

Automotive is one industry where performance and regulations are driving the continued development of new synthetic oils.

© Can Stock Photo Inc. / Frankljunior

BASE FLUIDS FROM RENEWABLE FEED STOCKS

Many start-up companies in North America invest heavily in developing new synthetic base fluids from renewable feed stocks. According to Larson, this is because the fluids offer performance advantages. “Research is showing where they could provide performance advantages,” he says. “As long as they have unique performance attributes and aren’t a me-too offering, then they need to find the applications that could benefit. If there is a chance a new product from renewable sources gives an advantage to the automotive market and improved efficiency, they would look at it.

“If they are entering a space where 99% of the market is served by mineral oil, which is cheap and works well enough, the adoption is either performance or regulatory based. Performance applications could use them where using mineral oils will not meet certain requirements such as fire resistance. The marine market is just one area where they are needed because an EPA regulation was issued requiring the use of readily biodegradable fluids,” says Larson.

At the end of 2013, the EPA issued the Vessel General Permit (VGP) that specified requirements for discharges of marine vessels. It covers a lot more than just lubricant, but part of it specifies Environmentally Acceptable Lubricants (EALs) and who has to use them (all commercial vessels greater than 79 feet long). They must be readily biodegradable, have low eco-toxicity and be non-bioaccumulative. According to the EPA, the impact of lubricant discharges (not accidental spills) to the aquatic ecosystem is substantial.

“The regulation has been out for two years, but adoption takes time and there are many loopholes for exclusion,” Larson says. “All vessels must use an EAL, unless technically infeasible. If they have reason why it is technically infeasible, then vessel operators have to specify in writing why they don’t use them and report the use of a non-EAL. For example, some vessels only come into port once a year and have only one chance to change their fluids; it will take time.”

Larson says there is a need for new oils from renewable feed stocks. “Regulations like the EPA VGP have to be in place to dictate someone to use it. Many industries have been using mineral oils for decades. If the government tells them they have to change, they will. But they won’t just pay more for a fluid. There has to be a reason to do it. Sometimes biofluids have performance disadvantages along with a higher price, so the regulations have to be in place to get them to be considered.”

Although currently the only regulation is in the U.S., other regions are adopting voluntary programs such as the European Ecolabel, which requires more than 50% of a lubricant be from renewable carbon sources and more than 90% readily biodegradable for hydraulic fluids. Larson says, “For a hydraulic fluid to have this label, it would need to use renewable base stocks. These aren’t government regulations, but labeling programs like these do promote the use of renewable sources. A cruise ship may be interested because they can promote or advertise about their use. Sometimes it is up to the end-user or consumer to drive its use if they want it.”

Biosynthetic Technologies is an example of a start-up company that believes there is a need for new base fluids from renewable feed stocks. It has operated for six years developing, manufacturing and marketing new estolide ester materials. The estolide molecular structure was invented and patented by the USDA using catalytic reactions to convert fatty acids in vegetable oils into synthetic ethers. These estolides are marketed as

biosynthetic base oils—a new class of biodegradable and non-toxic esters. Biosynthetic Technologies has exclusive rights to this USDA technology and has filed almost 100 patents covering the molecular structure as well as the methods of fabrication, the catalysts and the use of the molecule in products like motor oil and greases.

Biosynthetic Technologies’ biosynthetic base oil received ILSAC GF-5 certification. (Photo courtesy of Biosynthetic Technologies.)

Biosynthetic Technologies’ biosynthetic base oil received ILSAC GF-5 certification. (Photo courtesy of Biosynthetic Technologies.)

Biosynthetic Technologies has partnered with Albemarle Corp. to build a continuous flow demonstration plant at Albemarle’s chemical plant in Baton Rouge, La., and is now moving forward with Albemarle on construction of a commercial production plant. This catalytic process uses typical petrochemical equipment, catalysts and processes. CEO Allen Barbieri and Chief Technology Officer Jacob Bredsguard, both STLE members, explain their success in optimizing the process for scale-up to a full-scale commercial plant in Texas, which will break ground in midyear.

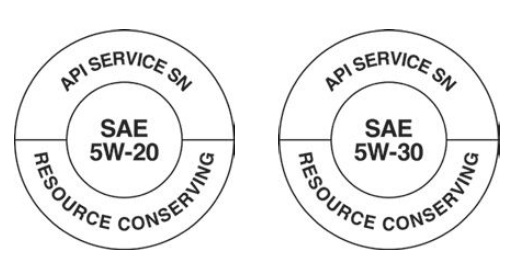

Barbieri says the product this start-up offers has both performance and environmental benefits over PAOs, other esters or Group II or III base oils. Many oil companies and other distributors of lubrication products have been performing field trials, tests and validations for the last several years. One major additive company has achieved API SN and ILSAC GF-5 certifications after testing and validating 5W-20 and 5W-30 (

see Figure 1) formulations of motor oil. Barbieri also expressed customers have proven significant performance benefits seen when these biosynthetic oils are used as a co-blend in formulations for metalworking fluids, greases, hydraulic fluids and gear oils. No products are for sale yet, but production samples from the demonstration plant are helping prepare to launch commercial products that are expected to sell at lower costs than high-grade Group IV and V products when the full-scale plant comes online.

Figure 1. API certification of 5W-20 and 5W-30 motor oil with Biosynthetic Technologies’ biosynthetic base oil. (Photo courtesy of Biosynthetic Technologies.)

Figure 1. API certification of 5W-20 and 5W-30 motor oil with Biosynthetic Technologies’ biosynthetic base oil. (Photo courtesy of Biosynthetic Technologies.)

According to Barbieri, many formulators are willing to invest in assessing new technologies derived from non-petroleum feed stocks. Many major lubricant companies are currently evaluating Biosynthetic Technologies’ product, including major oil, lubrication and chemical companies, as well as two automaker OEMs.

Metalworking is one of the spaces with more visibility and where PAGs offer numerous benefits.

Metalworking is one of the spaces with more visibility and where PAGs offer numerous benefits.

© kadmy/iStock/Thinkstock

He says certain regions of the world are more receptive to trying new technologies, with Europe being the most receptive to environmentally friendly products and with some areas in Asia showing surprisingly high levels of interest as well. He says, “China is taking a very strong look at the fuels and chemicals they’re using because of the high level of pollution in their environment. Over time, we expect to see many more regulations encouraging their use.”

Beatty agrees that there is a need for renewable feed stocks. He says, “This is a big thing in esters because by their nature their fatty acids can come from petrochemical or plant or even animal sources. The fatty acids used in esters often are byproducts of agricultural products. They are successful because good products are able to be made from very low-cost feed stocks.”

Biomass feed stocks are the plant and algal materials—such as corn starch and crop residues—used to derive fuels.

Biomass feed stocks are the plant and algal materials—such as corn starch and crop residues—used to derive fuels.

© PRImageFactory/iStock/Thinkstock

However, Beatty adds that there are only certain areas where using renewable feed stocks matters. He says, “Any fluid serving U.S. government applications must meet the mandate for renewable content in the fluid. Other than government customers, no one has ever asked me if the base stock was renewable in 27 years. In today’s industry, customers want performance, price and sometimes biodegradability when they have to dispose of things like condensates from compressors.” Beatty says there will be a big future for new base oils from renewable feed stocks under two conditions: they perform at least as well as existing products and they are priced equivalently.

INNOVATION DRIVES DEVELOPMENT

Beatty says in North America there are many customers who want to have proprietary patented products and own the intellectual property, and a novel base stock is one way to get that. Extended life and other performance factors cause them to look for new base stocks, but patent protection is the real hook. In Europe there is more interest in better performance, and everyone in the compressor market is looking for new varnish-free products with longer life and better resistance to bad environments.

Another important driver for new base oils, according to Beatty, is the abundant supply of natural gas. He says, “Looking for ways to use gas and increase its value is like bringing a solution and looking for a problem. Making a good quality base stock from it is not looking for a better base stock. Gas to liquids are not performance driven but rather strictly an economic consideration from a much lower cost feed stock.

“Metallocene polyalphaolefins are next-generation products that are much better than traditional PAOs,” Beatty adds. “They have higher VIs and better oxidative stability and are at a cost fairly comparable to regular PAOs. It arrived on the market knowing that it would replace existing PAOs and other base stocks. There is not a machine out there sitting idle waiting for someone to develop a lubricant for it. Everything is running on something. All lubricants displace others because they are either better or cheaper. It is the same for base fluids. Create something better, do the same for less money or come up with something evolutionary that could be used in applications that were more expensive to fill. When there is a better product, customers will gravitate toward it.”

Governments also are helpful in supporting the use of new non-petroleum derived products for lubricant components in several ways. According to Barbieri, they are helping with financing, the use of biobased products and regulations that would potentially require their use.

The USDA’s BioPreferred® Program requires government agencies and contractors (such as FedEx and UPS) to use biobased products when they are available. They created a category for motor oil and specified a minimum 25% biobased content to meet the requirements. Barbieri says other countries are setting up similar requirements for their government agencies. He expects in the long term there will be some level of requirement that all motor contain some level of environmentally friendly ingredients, since it often drips out of cars and is illegally dumped down drains, polluting our water.

The USDA will act as guarantor of a bank loan for Biosynthetic Technologies to construct its first commercial plant. Biosynthetic Technologies also is working with and will be announcing that several departments in the federal government will start using its product, as well as three branches of the military and other agencies in a select number of passenger cars and non-passenger vehicles in their fleets.

MARKET CHALLENGES

Small companies are at a distinct disadvantage when it comes to introducing new synthetic base oil technologies because of the costs to manufacture. Beatty’s company didn’t develop new base oils; he created new formulations from those that were available. He says, “Big companies are more likely to come up with new base fluids because they have access to low-cost feed stocks, and they already have spent the capital to synthesize things. It’s easy to be a blender but takes a lot of money to get into the feed stock business.

“The majors make PAOs and PAGs; start-ups don’t. Most of the oxides like ethylene oxide and butylene oxide and ANs will come from bigger companies. Start-ups also can’t create hydro-treated hydrocarbons. It takes refineries with hundreds of millions of capital and production on a big scale to create them. Although there are a few companies that are trying to create novel base stocks that seem to be fairly small, they didn’t differentiate themselves well. They didn’t offer anything that couldn’t be done with existing base stocks,” Beatty says.

“Esters are the only thing that will be in the range of someone starting up working with limited capital,” Beatty says. “They are one of the simplest things to make and don’t take a lot of hardware to produce. There is no limit to the number of esters that can be made, especially if they are made on the small scale. A different ester comes from every different fatty acid. That’s the main thing a start-up can accomplish in base fluids.

“The reason most new things fail in this industry is not for lack of marketing. Everyone looks at something new when it comes along. It’s usually that the product doesn’t have a niche. Most new products do the same things as other products and offer a different way to reach the same results. This is the biggest challenge for start-ups,” says Beatty.

Larson agrees. He says, “Synthetics have the stigma that they cost more. A benefit has to be proven. New products have to meet the performance requirements. If performance improvements can’t be demonstrated, end-users won’t be interested. Unless there’s a regulation to meet, the product must have an advantage. If the regulation can be met, it can save the customer money by avoiding fines. Then, once a benefit is proven, the biggest barrier becomes cost.”

It takes time for new technologies to penetrate the industry because testing every application takes a long time and a lot of money. There are many standards a new product has to meet. Combined with long development cycles, OEM approvals, ASTM testing and working with formulators, Larson says, “A quick cycle for a new product to get into a new application is a few years. It takes longer to get into higher end applications like aviation. Start-ups won’t see quick returns and most can’t wait that long. Trying to introduce a product into an application in a year won’t be successful. It’s important to understand what’s needed from a regulatory and certification standpoint first, find someone willing to accept it and want to try it and then take the time and money to do it all.”

Barbieri says one of the biggest barriers to start-ups is the cost of testing and validating new formulations. He says, “It is expensive to change a formulation and do engine or equipment testing. Some applications like motor oil require regulatory approvals and certifications. While some customers aren’t willing to test a new product in their application until it is commercially available, others are happy to. Validating that a product has a performance benefit sometimes can take several years of testing, along with a cost.”

Another reason it is difficult for start-up companies with innovative technologies to penetrate the industry is they are competing in an industry that has been in existence for more than 100 years and has become very efficient. Bredsguard says, “To survive, start-ups must compete with price. It’s not possible to be in the market in any significant way if they don’t. Although some new technologies may have inherent manufacturing benefits or use lower cost feed stocks, it is hard to compete in a very old, stable, commodity-type industry that has economies of scale generated over decades. The investment requirement is a challenge when it requires hundreds of millions of dollars to create and manufacture at a scale that is price competitive. However, esters is a sector where such new products can compete. There are few esters that are produced in high volumes and at low prices. This is where Biosynthetic Technologies can easily compete while we scale to higher efficiency output.”

Technically this also is a challenge. Start-ups have to do many things to develop products and processes with a low cost to produce that have comparable or improved performance characteristics so they can compete and offer an advantage. For four years, product and process development at Biosynthetic Technologies centered on keeping costs down and delivering something the market wanted. Its product is biobased, which always generates curiosity, but Bredsguard says it also delivers real benefits and performs well.

Biosynthetic Technologies’ new product is made with equipment and processes common to the petrochemical industry, integrating into existing infrastructure. It is made by a continuous process instead of a batch process because it is more efficient. There are several recycle streams in the process so unreacted feed stock is not lost and there is extremely little material waste.

Performance characteristics were improved iteratively with feedback from the market who sampled the product. BP as an initial investor helped Biosynthetic Technologies get off the ground. Bredsguard says, “Once our technology worked well in a motor oil, things took off. Having a working ILSAC GF-5 grade motor oil was impressive to many in the industry. It provided a lot of validation to the overall formulation and things took off.”

LESSONS LEARNED

Bredsguard mentions that this industry doesn’t change quickly or easily. He says, “Products that are in use now were used 40 years ago. Although the manufacturing and processes have changed, it’s not a terribly entrepreneurial industry. Once a company is in and becomes established, it’s easy to grow as your product is seen and appreciated. Newcomers should expect that it will take many years to break into this industry. Product testing takes years to perform. It takes focus and patience.”

Barbieri says the key to their success is that they are working with oil companies, not competing with them. He states, “Our largest shareholder is BP, an oil company that was looking for a new technology it wanted. Today we are working with more than 80 major lubricant formulators. There is always a strong interest in improving performance. It’s important to understand what benefits the industry is looking for such as lower deposits, higher oxidative stability and higher VI; then you must be patient while the industry slowly adopts your new technology. That part hasn’t been easy, but having the formulators do the heavy lifting, developing and certifying the formulations, then pushing these products to the end customers simplifies our business model, allowing us to focus on product development, leveraging the formulation and distribution infrastructure of these big companies.”

Another lesson learned that surprised both Barbieri and Bredsguard was the degree to which companies are willing to spend a lot of money testing a product before it is commercially available. Barbieri says, “A finished product field trial campaign can cost $300,000 to run. The willingness for our major customers to spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, in a few cases millions, testing our products shows that there is a significant level of interest in the market.”

REVOLUTIONARY CHANGE OR THE TRADITIONAL CULTURE

Whether formulators look for and adopt revolutionary changes and new technologies versus preferring the traditional evolutionary culture depends on the product itself. Beatty says there is a need for both. He states, “That’s something that is unique about this industry—the pace of development is very slow. It takes decades for incremental improvements to happen. If it is a better product, it will do well. No one has stumbled on anything that has totally changed the world in this industry recently, but we’d love to have something revolutionary pop out. There is no fear of that and no barrier to entry. For example, if someone brings something with tremendous oxidative stability that has all the desired properties, it would be formulated and tested as quickly as possible, without hesitation. But it’s just not there. People have been looking for a long time. Most of what has come around is evolutionary, not revolutionary.”

Barbieri says the revolutionary aspect of a new product can be problematic: “While our products offer a strong environmental marketing story, better technical performance and better fuel economy, the higher product validation and certification costs will still cause many to delay adoption of these products.”

According to Larson, there is always an interest when something new comes along because applications are getting more demanding. He says, “As manufacturing processes speed up to push products out faster and reduce the footprint of equipment to produce more in a given space, lubricants have to handle higher temperatures packed in smaller spaces for longer times. Oil-soluble polyalkylene glycols got people’s attention. It was a novel product offering a big change. They provide the benefits of traditional PAGs and also are oil soluble. That was more than seven years ago, and they are still considered new. The industry is still finding new ways to use them.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

American Chemical Technologies:

http://americanchemtech.com

Biosynthetic Technologies:

http://biosynthetic.com

The DOW Chemical Co.:

www.dow.com

EPA Vessel General Permit (VGP): Available

here.

Debbie Sniderman is an engineer and CEO of VI Ventures, LLC, an engineering consulting company. You can reach her at info@vivllc.com.