What’s ahead for marine deck greases?

Stuart F. Brown, Contributing Editor | TLT Technical Update May 2015

The lubricant industry braces for another round of regulations affecting these unique substances.

www.canstockphoto.com

OCEAN-GOING SHIPS ENCOUNTER WIDELY FLUCTUATING CONDITIONS as they transport goods and materials between far-flung ports. The same ship may travel across the Atlantic from Northern Europe during the winter months, for example, then switch to a route leading through the Suez Canal in the summertime. The grease that lubricates its topside-mounted machinery must perform well across a broad temperature range in conditions varying from warm sunny days to frigid storms that send salty waves crashing across the decks.

For defense against the ravages of corrosive salt, ship operators depend upon specialized grease to protect metal machinery exposed to the elements. Although it is referred to as marine deck grease, the lubricant isn’t intended to make ship decks slippery—that’s nobody’s goal. Rather, it is used to protect the equipment atop the decks from water ingress and corrosion caused by seawater’s nasty salinity. This hardware can include winches, wire ropes, cranes, valves, hatches, hinges, bearings, sliding components, gears and other devices that will quickly rust unless they are kept coated with a film of grease (

see Figure 1). Marine grease finds similar uses in dockside equipment such as cranes used for loading and unloading ships.

Figure 1. The typical applications of a ship. Marine greases must be able to protect machinery from the damaging effects of saltwater. (Illustration courtesy of Total.)

Figure 1. The typical applications of a ship. Marine greases must be able to protect machinery from the damaging effects of saltwater. (Illustration courtesy of Total.)

What defines grease? It’s a lubricant material made from varying amounts of three components: oil, additives and thickener. Oil accounts for 85%-90% of the product’s volume, with additives making up 1%-15% and thickener making up the rest. Think of it as a clingy gel that contains a high portion of lubricating oil. Grease is chosen for uses where adhesion is valued—jobs where liquid oil would merely drip off the parts needing protection.

Marine greases are typically formulated using lithium, lithium complexes or calcium sulfonate complex as a thickener. A maker of the latter type is the specialty chemical company Chemtura Corp. based in Middlebury, Conn. In the mid-1980s Chemtura patented a calcium sulfonate complex formulation that it developed into a family of products serving many industrial markets. Chemtura began producing marine grease in the early 2000s under a private label for a major oil company partner. Chemtura also has launched marine products under their own Anderol® brand.

Chemtura saw marine applications as a natural fit because the thickener structure it developed has excellent inherent corrosion protection properties. Calcium sulfonate thickeners also have excellent antiwear and extreme-pressure attributes, eliminating the need for special additives to impart those characteristics. Grease used above the waterline on ships needs to protect equipment from heavy loads and from shock loading that occurs when the work cycle alternates abruptly between loaded and unloaded conditions.

Marine grease is formulated to be pumpable so that ship maintenance crews can apply it to machinery with grease guns, although some vessels are outfitted with labor-saving central lubricating systems. Wire ropes may be fitted with pressurized collars that apply grease as the strand moves through them. Below decks, crews may use a bucket and a stiff brush to lubricate mechanisms such as steering gear.

“Lubricants on a ship have to meet increasingly stringent environmental requirements,” says STLE-member Wayne Mackwood, R&D manager, detergents and grease, at Chemtura. “We will eventually need to redevelop our products based on a fluid other than petroleum oil, and these new products will need to avoid use of harmful materials that might not be acceptable if they should get into the water.”

Meeting the new requirements has the industry’s research and development departments exploring environmentally acceptable lubricant (EAL) formulations using ester-based fluids, either natural or synthetic, made from canola oil or from synthetic stocks. The challenge is trying to find ways to use the best thickening technology with these newer fluids.

Thickeners can be simple soaps—a fatty acid reacted with a metal base—such as lithium, lithium stearate, calcium stearate or aluminum stearate. They can also be complex soaps containing lithium complex, aluminum complex, calcium complex or calcium sulfonate complex as co-thickeners. Oil may be thickened with non-soap solids such as clay and silica gel and also solids such as molybdenum disulfide or graphite.

When grease formulators need an additive with antiwear properties, zinc dithiophosphate is a common choice, as are phosphate esters. Sulfonates are the most popular anticorrosion agent. Extreme pressure additives include active sulfurs, sulfides, dithiocarbamates and molybdenum. Anything used in an EAL-approved grease will come under scrutiny, and, therefore, a grease with multiple key properties inherent in its structure may offer benefits in this area.

As they explore the possibilities for developing an EAL-rated deck grease, researchers will have to learn more about non-mineral oils. For example, a small number of companies are looking for new ways to synthesize biofluids.

“Regulation will drive this,” says Mackwood. “Certainly without regulation it will prove difficult to introduce a product that could cost twice as much without significant improvement in performance. Even with regulation, our goal remains to develop a new product that has acceptable cost as well as showing performance benefits over the existing technologies.”

Total Specialties USA, based in Linden, N.J., is the local affiliate of the big French national oil company Total. Through its Lubmarine division, Total is one of the major suppliers of marine lubricants, including deck greases. STLE-member Darren Lesinski, technical director of Total Specialties USA, says, “What’s affecting us most here in the U.S. is the Vessel General Permit (VGP) compliancy ruling put forth by the EPA.” The latest revision of the VGP ruling was established in 2013 and covers all ships 79 feet or longer operating in U.S. waters. Every five years the VGP will be updated to reflect changing conditions and technology.

Such ships—many of them large freighters and tankers—must comply with EPA rules regarding biodegradability, toxicity and bioaccumulation of the lubricants used on board. Luxury passenger cruise ships also fall under these rules, while U.S. Navy and Coast Guard ships follow their own strict procedures for selection and storage of lubricants. (Non-recreational commercial vessels such as fishing boats fewer than 79 feet in length are covered by a separate Small Vessel General Permit.)

The EPA VGP rules grant exceptions for equipment filled by the OEM maker’s factory with a lubricant that for recognized technical reasons cannot be made biodegradable, bioaccumulative or have the required minimal toxicity level. Operators of ships thus equipped must be prepared with appropriate paperwork from the original equipment manufacturer when the Coast Guard or the EPA boards them for an audit.

Total Lubmarine’s EAL-rated greases are thickened with either a lithium, calcium-lithium or calcium thickener, depending on the shipboard application. A tackifying agent is added to grease used on wire cables or chains that may be part of a ship’s anchor system, for example.

Today’s eco-friendly grease formulations use a base oil of vegetable oil, synthetic ester or glycol-based oil. “Esters get expensive so there’s definitely a decision owners and operators must make between a high-tech synthetic ester and a vegetable oil-based ester,” Lesinski says. If the application involves equipment that gets hit with a lot of seawater, the crew may have to be constantly relubricating, so the grease is treated as a once-through lube. Operators have to decide if it’s beneficial cost-wise to go with a synthetic or vegetable-based ester.

The rules keep on piling up. Any ship that enters U.S. waters has to comply with the EPA VGP rulings. On top of this, individual states have their own sets of rules and regulations integrated into the VGP for their waters. Florida, for example, has pretty strict effluent limits on oily mixtures, anything that can discharged from a deck. Tourism and sportsman activities like fishing are a big industry in Florida, so the state wants to protect its environment.

Do crews lube equipment underway on the seas? On long voyages, the answer is likely yes. But many freight and cargo ships, and also luxury liners, will lubricate everything that needs it when they are in dry dock for periodic maintenance. Lesinski says there are two trends underway that reduce the amount of crew labor devoted to lubricating ship systems. One is the growing adoption of auto-lubricators that automatically supply grease to multiple pieces of deck equipment, and the other is the use of bearings made with special plastics and metallurgy that don’t have to be lubricated.

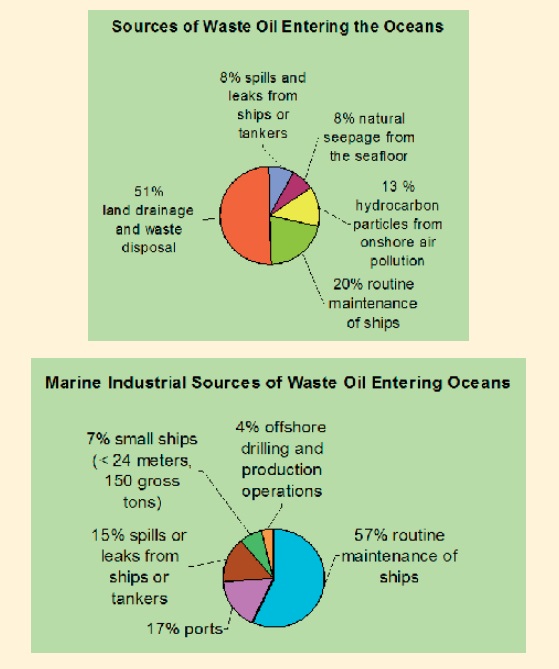

While the U.S. led the way years ago in mandating pollution-control technology on automobiles, European countries were the first to apply environmental standards to discharges of pollutants from ships in biosensitive coastal areas (

see Figure 2 for more information on sources of oil pollution). The U.S. EPA followed suit, building its rules specifying and approving lubricant products on the European model. As a result, products certified by the EU will be granted use of the EU Ecolabel to be applied on product labels and data sheets.

Figure 2. Sources of oil pollution entering the oceans. (Graphs courtesy of Total.)

Figure 2. Sources of oil pollution entering the oceans. (Graphs courtesy of Total.)

It’s expected that the next revision of the VGP will expand its purview to products that cause a rainbow-tinted iridescent sheen on the surface of the water. Most mineral and vegetable oils diffract sunlight when it strikes their hydrocarbon molecules, producing the sheen. Certain glycol-based lubricants, with their oxirane molecular arrangement, reflect light in a different way, making them the choice if new regulations specify non-sheening performance.

This is what lies on the road ahead for grease makers and formulators. Big agencies like the EPA and Europe’s counterparts will periodically cook up a new version of the rules. It’s the job of the lubricant people to imagine new products that could fit the bill.

Stuart F. Brown is a free-lance writer who can be reached at www.stuartfbrown.com.