A history of the lubricants industry in China

Paul Turner | TLT Feature Article May 2015

Opportunities are limitless for marketers who understand how to do business with what will soon be history’s largest economy.

www.canstockphoto.com

I WOULD SAY THE VAST MAJORITY OF PEOPLE READING THIS WERE BORN BEFORE 1980 and most of us well before then. I was just about to start high school in Australia in 1980. Australia was and still is an industrialized nation, has mature industries, banking institutions and a well-educated workforce. For a high-school student looking toward the future, there was a linear line and choices for a number of careers if I applied myself. And it would have been the case for most if not all of you. A great Australian life in retrospect. The simplest of lives. No struggle for food. Education for all citizens. When sick, saw a qualified doctor. Slept when tired. Ate when hungy. Drank when thirsty.

Schools and resources barely existed in China in 1980. China was an exhausted and impoverished nation. From 1840, with the first Opium War against the British China, China stumbled and fell into the 20th Century as a nation kicked around by the then current various masters of the world. World War II, which for Chian began in 1937 with the invasion of Japan, brought this once leading tecnological country for the past 2,000 years to it knees. Civil war and independence followed after a century of being kicked around. And kicked around is how the Chinese see it.

When the communists took over the government in 1949, China’s population was 549 million. In 2000 1 billion. 50 years. Today it is 1.3 billion. An extraordinary growth and one that has provided the basis of the last 30 years’ enormous growth via the labor market and also the many headaches for the Chinese government. But in 1980 the education system had just started again after coming to a complete standstill the previous decade. Banking and capital institutions were moribund and weak. No one owned property, no one owned a business, no one had an avenue to capital with the chance to be able to get product to market. China was weak, fragile and essentially a basket case. The entrepreneurial spirit extinguished.

In 1980 bicycles were among the top pieces of machinery in China requiring lubrication.

In 1980 bicycles were among the top pieces of machinery in China requiring lubrication.

Perhaps China's most famous aphorism is that each journey begins with the first step. And China took it. Within our lifetimes China went from peasant farmers, extreme poverty, political divide and a dilapidated education system to a sophisticated, diverse with multiple institutions in manufacturing, finance, automobiles, education and tourism. China was big enough to get the world out of its financial crisis in 2007-2008. Today it is the world’s second-largest economy on track to become the largest, and it won’t stop there, not by a long shot. Some 200-300 million people have a lifestyle equivalent to the West’s middle class. China has a billion to go before it will be satisfied.

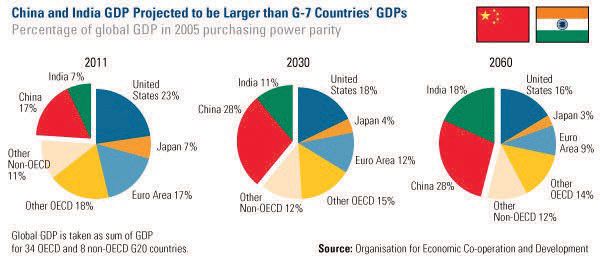

The Chinese see the last 200 years as a bit of bad luck, and now is the time to take its rightful position at the top of the heap of world countries. I am not here to give a generic economic history of China since 1980, but I will try and give some insight into one industry: the lubricant industry that was affected by all the changes that happened in China in the last 35 years and what the future might hold socially, economically and politically. See the chart with OECD projections.

The GDP projections for India and China through 2060.

The GDP projections for India and China through 2060.

By 2030 China will be almost double the size of the U.S. in economic terms. I think everyone reading this needs to be fully aware of the impact this will have on every industry. We have watched China, we have read about it, we have been amazed about it, but I am not sure large and middle companies and governments were doing enough about it. It is a behemoth like no other. It is the elephant in the room.

In Europe and the U.S., many still believe that China cannot be sustainable. That there will somehow come a day when this juggernaut will falter or political turmoil will cease development and it will all come crashing down. I don’t see any evidence for that. If anything the Chinese see the reverse to be more likely, and Europe and other industrialized nations are the ones that are the most fragile. China has no government debt. After all, many industries worldwide are being propped up by Chinese capital, Chinese investment and Chinese consumer sales. What would GM be today without its Chinese market, I wonder?

In 1980 China had two good things going for it—an enormous pool of labor and potential. Initial reforms started with farms as they were no longer “communed,” which meant that extra produce could be sold. This meant income, savings and capital, albeit on a small scale. It was a deliberate policy from Deng Xiaoping to promote farmers first, as they were and still are the largest constituent. Banks were created for various industries and lending capabilities began for state-owned businesses to allow them to expand.

Urban dwellers had to wait their turn until the 1990s and 2000s for the housing and ownership reforms that helped them. There was no such thing as a mortgage in China until 1998. Prior to 1998, urban dwellers were essentially given the houses they lived in (owned by the state via the state-owned company they worked for) for a small amount of rent in which they could live forever. They ate together in the same canteens, dressed the same, read the same and watched the same movies in community centers. They received—more or less—the same pay and celebrated the festivals without fuss centered around food, which of course remains a vital and important part of Chinese culture. A dull life but better than it was. You were eating well. Your teeth were looked after. Protein via pork and chicken was no longer an issue. These were the good times compared to the 150 years that proceeded it. Colors bloomed, girls grew their hair long and boys wrote poetry. But then things went up a level and really got interesting.

After 1998 China changed direction. You could buy the house you lived in, remarkably cheaply and own outright, which set off the housing market, slowly at first as people got used to this peculiar thing called personal ownership. This inadvertently set off divorce rates. It meant the state had to find another unit or usually house unit and in turn you could buy that, essentially setting up a family with two properties. When the government caught up with this little trick (or perhaps encouraged it), the clever ones mostly in Shanghai and Beijing simply remarried and used the houses as basis for credit and mortgages. It set off the housing boom that has gone unabated since but also allowed entrepreneurs to utilize this new capital, and in the early 2000s China went boom.

Along with the easing of foreign investment regulations, a banking system became more dynamic and learned how to make money via lending and investing inclusive and was willing to lend as they too sought to profit from deregulation—to a point. Hong Kong and Taiwan played enormous roles in providing capital and setting up property and businesses throughout China mirrored their own mature banking, legal and corporate systems.

There were enormous setbacks as China was still embracing change or at least wondering whether change was a good thing. The events in Tiananmen Square in 1989 slowed the government’s process but didn’t stop it. The world saw the harshest part of China’s transformation. More a reaction to change than a demand for democracy, but I am not sure anyone in the West at the time saw it that way. China was isolated again. Sydney beat Beijing for the 2000 Olympics; companies that were looking at investing in China balked and waited. But to Deng Xiaoping’s credit, he forced China forward. It kept investing and changing. Eventually the Chinese themselves saw change as normal and embraced it. There was a growing middle class that aspired to grander things, farmers saved and invested in their children’s futures. The slowly building middle class became aspirational, and the few rich even started playing golf.

When I arrived in Shanghai in 2000, there was one subway line that cut beneath the city west to east. By 2010 there were 16 lines as Shanghai showed itself off to the world by holding the International Expo. But it took effort, pain and inconvenience. Inconvenience is something China knows well and tolerates.

In the 2000s Shanghai and Beijing were under construction 24 hours a day. Each street had something being pulled down or being built. Every single one it seemed. These now shining metropolises were noisy, dusty and polluted. They are still polluted but getting better, and it is now government policy to clean them up. But the nation pulled it off, and by 2008 when Beijing had held the Olympics, the rest of the world was screaming toward a financial crisis and a growth paralysis. It seemed China would also fall prey to the international financial stresses it was now wholeheartedly a part of.

Not China. China saw it and banked for it.

It had all the equipment it needed, all the technology it needed, or if it didn’t it could invest in it and create it. Trillions of dollars in foreign savings and all of a sudden it was the rest of the world that turned to China for help. That is a turnaround of just 35 years.

Beijing lubricant storage in the early 2000s.

Beijing lubricant storage in the early 2000s.

It seemed that no one noticed this change in global politics and economics until about 2005. All of a sudden everyone clamored to get on the China bandwagon, but it was China that dictated terms on how you could invest in China. For foreign investors, the future for China is no longer just its large manufacturing base for making cheaper products but its many varied industries, services, banking, transport, tourism and education. And of course the lubricant industry is one of them.

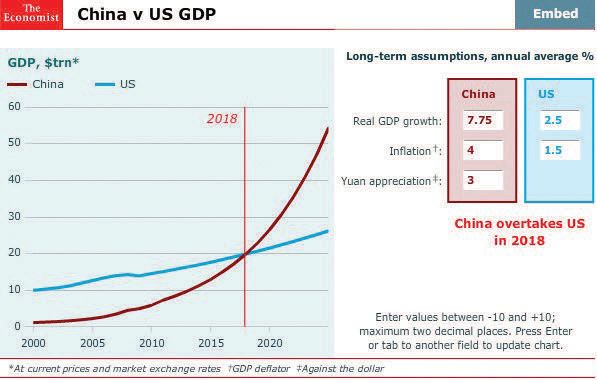

The GDP of China versus the U.S. in the coming years.

LI JIA

The GDP of China versus the U.S. in the coming years.

LI JIA

In 1980 the lubricant industry consisted of industrial yard productions in woks to produce lubricants. No quality control, no technology, no brands and no market besides keeping whatever machinery there was going. Mainly bicycles! By the 1990s large-scale manufacturing had arrived, foreign brands poured into China with technology, money and know-how, and the world was buying cheap products from China, keeping inflation down for nearly two decades for the beneficiaries of these products: the West. The Chinese lapped it up and kept on growing their own manufacturing plants and brands.

About this time a Chinese entrepreneur named Li Jia, armed with an architecture degree and a failed venture in the dog food market (the Beijing government banned dogs as pets for a couple of years in the early 1990s), saw an opportunity in the lubricants industry and jumped into the market with profound ignorance. But he learned and learned quickly. His first step was to make various lubricants with consistency. In a Beijing factory space he had a series of enormous woks 12 feet across and three feet deep trying to get a consistent heat and getting the right additives with whatever was available.

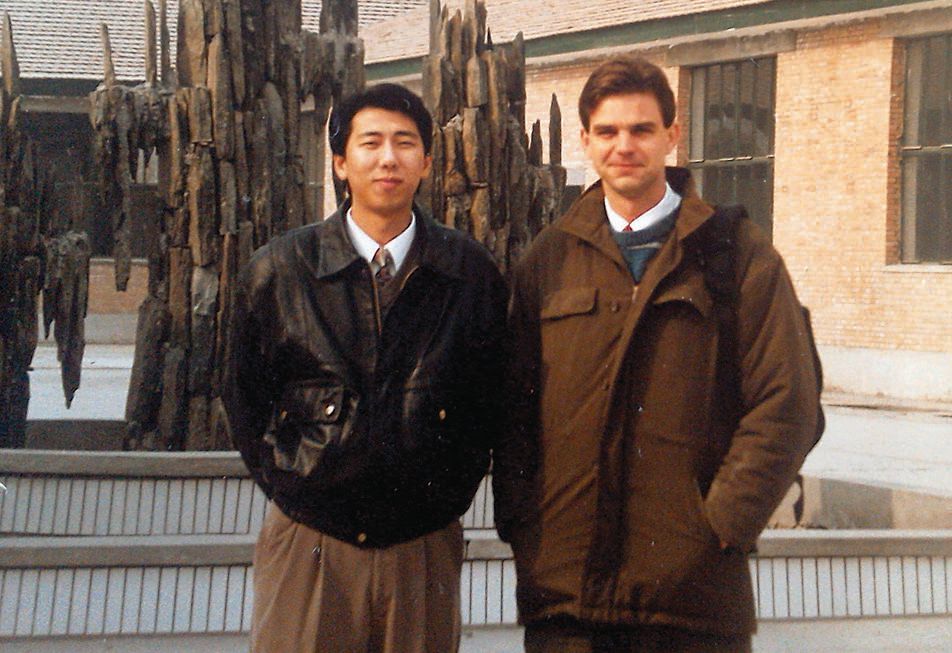

China lubricant entrepreneur Li Jia with Tongyi Petroleum Chemical Co. and Paul Howard, business associate.

China lubricant entrepreneur Li Jia with Tongyi Petroleum Chemical Co. and Paul Howard, business associate.

North and Eastern China were and still are the heart of heavy industry. Beijing, Tianjin, Shenyang, Changchun and Jinan were busy cities in the 1990s. But steel makers, car makers, fleet manufacturers, car parts, metal components for everything created a demand and need for lubricants.

Lia Jia’s product was called Monarch, and with a financial backer he got on the road to sell the product. The dusty roads of Northeastern China were unforgiving places in the 1990s. Competition was fierce, but due to the consistency of his products, he was gaining popularity and something else—notoriety. He escaped knife fights, countless threats and eventually—surely a sign of success—counterfeiters. He said he had to constantly change the branding and packaging of his product because within 13 days of putting a new product or brand out it would be copied and distributed.

Obviously the copies were of inferior quality, but it was a constant battle for market share as it still is. Despite the obvious concerns with fake products that are still an issue, it does show that there was a growing market, a demand for quality and a strong entrepreneurial spirit—something the Chinese government always had to catch up on as its people ran ahead of them both legislatively and in policy. More often than not the government quickly caught up to open more opportunities and provide better safeguards for brands and quality issues. But it still needs to be policed with harsher fines to make a bigger impact. The main problem with a developing country the size of China is that there is so much to do. Not only is this behemoth changing, it needs to legislate for those changes to occur without backlash.

Back to Li Jia. After 11 years of making lubricants in giant woks, walking through the Dickensian streets of industrial China selling his wares and setting up (most importantly) distribution networks in second- and third-tier cities, his Monarch brand, via his company Beijing Tongyi Petroleum Chemical Co., was turning over $260 million (U.S.) annually. In 2006 he sold a 75% share to Shell, a major strategic move that made Shell the leading foreign brand for market share in China. In every industry and every market there are thousands like Li Jia working their guts out and getting their piece of the pie.

Not bad for an architect. But Li Jia wasn't alone. Other companies that started up in the 1980-1995 time frame include Lanzhou Lubrizol Lanlian Additive Co., Shanghai High-Lube Additive Co., Liaoning Tianhe Chemicals Group, South Wuyi Additive Ltd, Great Wall (Sinopec-owned) and Kunlun Lubricant (PetroChina owned).

LUBRICANT MARKET TODAY

One of the most frustrating things for lubricant producers such as Mobil, Fuchs and Shell is the inability to get the latest developments and improvements in lubricants into the Chinese market. I hinted at it before. There is strict regulation about what chemicals and additives can be allowed into the marketplace. The lag between products ready for distribution and the legislation to be approved and allowed to go into the market can be years. It may be a deliberate policy for Chinese brands to catch up. The winter of 2012-2013 was a fulcrum for the government. The extraordinary pictures out of Beijing and other northern cities were literally breathtaking. The government realized that the best lubricants will play a part in curbing emissions and creating efficiencies. Hence the government is concerned with the quality of lubricants used and who is making them. There are currently about 4,000 lubricant producers throughout China of varying quality, and the government wants these reduced dramatically. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) will need to use premium lubricants with the inferior ones dismantled and banned via legislation and market demand.

This is where the foreign brands can get a foothold. All of the majors have joint venture deals with SOEs or private companies, but China obviously promotes its own. This is the China method. It learns what it needs to know and then goes ahead and makes it. In 2004 BP, Shell, ExxonMobil and Fuchs had 80% of the market for industrial lubricants. Today they hold about 30% of the industrial lubricant market, although a much larger market at approximately $60 billion (U.S.).

Joint ventures for Chinese companies mean capital, expertise and knowledge. For foreign companies it means access to the great Chinese market and all that potential—so they have to share the spoils. They don’t have a choice. Sinopec via Great Wall Lubricants and PetroChina with Kunlun dominate the marketplace (52% between these two brands), as was always Beijing’s intention. Only recently has a foreign brand been able to own gas stations. If you enter a gas station you don’t have to get out of the car. There is always a number of attendants that will do everything. Most do not have a shop, and if there is they rarely sell anything besides instant noodles and chocolate.

OIL ANALYSIS

The analysis industry is probably the last cab of the rank to start developing. The 1990s that roared for China meant that machines were simply run into the ground until they stopped. The common business practice was simply to buy another machine. Maintenance was not a top priority for most. Profits were high and growth exponential. The machinery bought from the U.S. or Germany and the maintenance brochures were not in Chinese! Tankers transporting diesel the day before would be filled with water the following day and something else the day after. No one was testing or overseeing what was placed in machinery; lubricants were lubricants and would simply be used across multiple machinery components without checking if there was a need for a different type of lubricant. Mechanics would use the same engine oils for cars, motorbikes, scooters and trucks. And the lubricant they used may or may not have been a fake or a copy.

The result was inefficiency and waste. Industrial accidents due to poor maintenance were a tragic consequence of the expansion of the Chinese economy in the 1990s and 2000s. I don’t know the actual figure, but China, due to most people living in high rises in their urban centers, had more elevators/lifts than anywhere else. The cables for lifts need a particular lubricant, and the amount of stories that are in the papers about lift shafts collapsing, causing injury and death, were numerous. That’s still the case today, albeit on a smaller scale. I have tried on many occasions to talk to companies that make lifts about maintenance procedures, and all are reticent to speak out in case it creates a business backlash. Again, regulations and organizations need to be created to oversee these issues and the Chinese are doing just that.

We run a Website in China (

www.olmzhoukan.com) that sends out weekly tips and also a newsletter that concentrates on lubricants, oil analysis and maintenance procedures. I believe we are unique to have articles about oil analysis in China. It is not widespread, and most would have no idea what you were talking about if you broached the topic. I have yet to hear a taxi driver who knows anything about engine oil analysis.

Of course it exists and has done so for quite a while. It is an industry that will grow exponentially over the coming years and decades. Certainly ExxonMobil is counting on it as it sets up a $60 million laboratory for oil analysis in Shanghai, the company’s largest in the world. It is enormous. Caterpillar, Fuchs, Shell and Volvo all have in-house laboratories that oversee their industrial after-sales services.

There are many private laboratories that are now opening up—the volumes are small for now—but the long-term goal is that it will grow, and grow it must. Samples that do arrive can sometimes be in Coke bottles, but this is changing as we ourselves make bottles for laboratories throughout China that are the equivalent of those we produce for Western laboratories. But every major analysis player is in China: Bureau Veritas, Inspectorate, Intertek, Analysis Inc., Oelcheck, ALS Global and others. They, of course, have their own networks as they have industries from their respective nations and regions that have set up in China and use the same maintenance practices. Again, this will simply grow into the future.

MEDIA

In 2000 there was no such thing as social media in China nor anywhere else for that matter. The iPhone, YouTube, Google, eBay and Twitter were still to be born and spread. The Internet was essentially new, while only some Chinese had mobile phones. By 2014 China had the most mobile phones in the world, and China’s eBay equivalent, Alibaba, was five times the size of eBay. They have all the equivalent social media that exists in Western countries, just bigger: Weibo, QQ, WeChat, Baidu, Youku, etc. With change being normal, the Chinese fell in love with new technology and transformed their businesses. It also meant intense competition between companies via outright fighting on blogs and forums. The Chinese love forums. It’s also the conduit for nationalism and that certainly filters its way into the lubricant industry. There are many lubricant blogs that are employees of SOEs or private lubricant companies that spend their time defending their products, ridiculing competitors’ products and promoting their company’s and nation’s products. It is a daily ritual to find comments like, “Only Chinese lubricants work in Chinese machines, and foreign lubricants are not suitable and can damage machinery.” The Japanese receive the most invective, but the rest get their fair share, too. Is this a sign of increasing nationalism or just the naivety of a very large but immature market? We at OLM spend a lot of time dispelling myths and putting forward practical information from reputable sources. There is a great deal of respect for certain worldwide brands, many I have mentioned already, that are now heavily invested in China. Germany has an unprecedented reputation in China due to its phenomenal industrial and automotive machinery. Almost every factory I visit has a piece of German machinery, and some are exclusively German.

Analysis and maintenance has huge potential. Companies are desperate for trained people, and the education around maintenance, conferences and training programs will become more and more the norm for companies to keep their employees up to date with practices. Certification from the world’s leading organizations and companies are now offering these. I have spoken over the last couple of years with STLE Executive Director Ed Salek and STLE director of professional development Bob Gresham about their steps getting into China, and I know they are very excited about the potential for their organization. And so they should be.

Australian mining companies have made great inroads into mining safety after thousands upon thousands have died over the last three decades. Such growth brings with it high risk, and cutting corners has brought too much tragedy to this sector. Factories are cleaner and more worker friendly than they were just five years ago. This is due to training and being in joint ventures with foreign companies that have standard workplace regulations as we would know them in the West that are now filtering through the Chinese industrial complex. There are opportunities galore with many more to come in the maintenance, workplace-training and analysis industries.

With more freedom and economic opportunity than ever before, the Chinese people have many reasons to be optimistic.

With more freedom and economic opportunity than ever before, the Chinese people have many reasons to be optimistic.

www.canstockphoto.com

SUMMARY

All politics are domestic. At first I didn’t want to end with a clichéd Chinese proverb, aphorism, expression or whatever you want to call it. But then I realized there was no reason not to. Chinese proverbs are wonderful and insightful. I tried to choose a profound one. A wise one. Perhaps a well-known one. I thought maybe the one about the three blind men feeling an elephant and asked to describe it. One feels the trunk and thinks it is a hose, the other the tail and says it is a whip and the third feeling its side and thinking it is a wall. That would describe China quite well. Large, complicated and interesting.

But I like change as well, and the modern aphorisms are gems. But my favorite is, “There is no need take your pants off to fart.” Which essentially means keep it simple. Don’t make things complicated for no reason.

I think we need to take that attitude to China. Don’t complicate a relationship with China via the baggage it comes with and the baggage the West brings with it in regards to China. China will do what it wants and will get what it wants to ensure its domestic well-being is looked after. Everything else is a distraction and is not priority. Many of you would not know the name of the foreign minister for China. For a country so large and having to deal with international issues, you would think his name would roll trippingly off the tongue. But the foreign minister and international issues are not priority. Wang Yi, who is the foreign minister, sits in the Central Committee that reports to the Politburo, which in turn reports to the Politburo Standing Committee. You can be sure when members of the Politburo Standing Committee sit down to discuss policy, the top 100 issues are all domestic.

Clinton Dines, who ran BHP Billiton in China during the 2000s, recalled this story of Wen Jia Bao, the former premier. Seems the European finance ministers called him from Brussels complaining about the strength of the Renmenbi (China’s currency). They nagged him about how it affected trade balances with Europe. Wen Jia Bao simply said, uncharacteristically vehemently, “We will move the currency when we think we should and not when you tell us to. We have bigger priorities.”

China will be an engine for growth for the rest of our lifetimes as it will be for future generations. It’s not going anywhere and will be the biggest economy ever known in human history very soon. According to Kline & Co., global lubricant demand is estimated at 39.5 million tons in 2013, up slightly from 38.8 million tons in 2012, with the Asia-Pacific region accounting for 43%.

What percentage of that is exactly contributed to China is never easy to pinpoint as figures are rarely released because companies are very protective of such information. Lubricants is just one of the many industries that will be on the ride that is the unstoppable force that is China.

One thing is certain, however. As the China juggernaut moves forward, lubricants will be the centerpiece of its future.

Paul Turner is managing director for OLM Group in Shanghai, China. You can reach him at paul.turner@olmjituan.com.