Manure spreader tribology—redux

Dr. Robert M. Gresham, Contributing Editor | TLT Lubrication Fundamentals February 2015

The newer designs incorporate many simple but highly effective engineering improvements.

KEY CONCEPTS

•

A manure spreader recycles nutrients to the soil and increases the amount of topsoil.

•

The newer manure spreaders have better corrosion protection, lube-for-life bearings and a more robust chain design.

•

The chain and ratcheting mechanism on the new manure spreaders function better with less corrosion.

SOME OF YOU MAY RECALL I ONCE WAXED AND WANED back in 2007 about the tribology of a manure spreader—“another tantalizing tribological taste of our industry at work.” Late last year STLE embarked on a study to identify new trends in our industry. Cited by many STLE members in the study was the trend toward mechanical systems that are more reliable and require lower-cost maintenance. Examples include better corrosion protection, lube-for-life bearings, etc. Now I recognize that more than a few of you might be exclusively urbanophiles, but for the agrarianly inclined, the application of these new trends is an exciting development of great importance to society that reveals how we overcome tribological challenges in a cost-effective manner.

A manure spreader manages a significant hygienic issue in an ecologically sound manner by recycling nutrients to the soil and increasing the amount of topsoil so more nutrients can be grown to feed livestock. Accumulated manure can pose serious run off problems, cause bad odor, result in bacterial, fungal and insect infestation and have a displeasing landscape. This is not trivial as the average horse generates 25 lbs. of manure per day, plus any urine-soaked bedding, leftover hay, etc. You can soon create a small mountain of very biologically live material in no time at all—which is great for the garden and flower beds. For people with livestock, this task is carried out 24/7, every month of the year. Figure 1 shows a manure spreader in action on a good day—it is only lightly raining.

Figure 1. Manure spreader.

Figure 1. Manure spreader.

So what about the tribology of a manure spreader? As you can see, it is essentially a two-wheeled wagon. In the older designs, the wheel bearings are sealed from the manufacturer and, thankfully, require little maintenance—that’s just about all the good news. In Figure 2, looking into the bed, we see two chains on either side with simple angle iron pieces spaced evenly running from chain to chain. As the chain is pulled toward the back of the wagon, the manure is fed slowly into whirling paddles that spread and disperse the manure evenly out the back.

Figure 2. Two-wheeled wagon.

Figure 2. Two-wheeled wagon.

Living on a farm with more than 20 horses, this is a topic I know a bit about firsthand. However, the particular manure spreader I described in 2007—my own—died an unceremonious death during the -15 F weather of last January. I bought a new spreader of the same model from the same manufacturer and noted a 20 percent higher price.

However, when the new spreader arrived, I was pleased to see the engineering improvements that nicely meshed the trends we identified in our study. Examples are better corrosion protection, lube-for-life bearings and a more robust chain design. So it struck me that it might be worthwhile to share a few of these changes to illustrate the point of STLE’s emerging trends study.

First, the chains on the old system are inexpensive metal stampings. This means that they have relatively sharp edges that preclude coatings or most lubricants to protect them from corrosion. Further, the bearing surfaces are also rough, adding to friction and wear (

see Figure 3). The new chains are made from rod stock so the only rough edges are on the cut ends (

see Figure 4), thus they have an inherently more corrosion-resistant shape and better bearing surfaces.

Figure 3. Old chain.

Figure 3. Old chain.

Figure 4. New chain.

Figure 4. New chain.

The older chains have another remarkable property. They only seem to break at below 20 F, especially if it is windy and snowing. As time goes on, constant exposure to the elements, manure, urine and wet bedding eventually corrode and weaken the chain. The stresses of winter put more strain on the chain, further increasing the probability of failure. Repair is simple enough: the tension on the chain is released, the chain is bent into position with just a few light taps of a hammer, the old link is removed and the new one installed. This repair, of course, happens only out in the field and only on a cold, windy, snowy day—during daylight if you’re lucky. The manure must first be dug out of the spreader, by hand, to access the chain. The light taps of the hammer are actually a bare-handed, knuckle-busting, operation that takes only a few seconds. However, the new chains are thicker, so it will take longer for wear/corrosion to do their damage. Also (and most important) they interlock simply, which can easily be done with a gloved hand. The new chains also are relatively inexpensive.

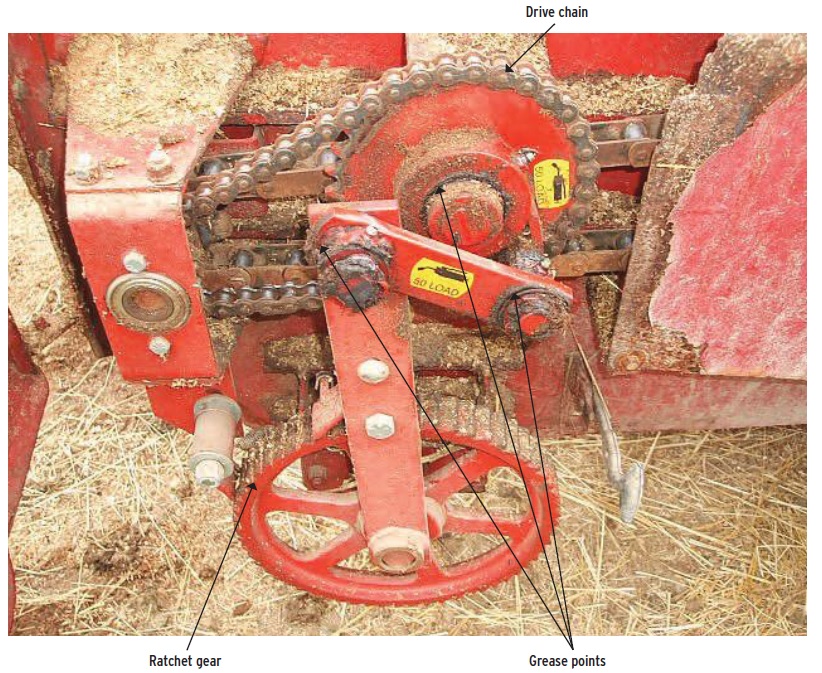

The next area of tribological interest is the ratcheting mechanism that pushes the manure into the whirling paddles to spread the manure. As shown in Figure 5, the older design mechanism is driven by another chain (like a big bicycle chain) that, when engaged, runs off a large gear attached to the wheel of the wagon. As the spreader is moved, the chain is moved. The mechanism has a large ratchet gear and a couple of smaller sprockets (all iron castings) that turn on a stationary journal. Each of these must be regularly greased (yes, in the rain and snow) with a good molybdenum disulfide-containing grease that preferably also contains corrosion inhibitors. Fortunately with regular maintenance, these greases perform well, and failures are rare. There are normally shrouds that cover this mechanism. Nonetheless, manure, rain and related detritus get in and around the mechanism. In Figure 5 you can readily see the corrosion on the forward shroud (to the right) that covers the bicycle chain running to the drive gear wheel.

Figure 5. Ratcheting mechanism.

Figure 5. Ratcheting mechanism.

The new design in Figure 6 (notice how much cleaner everything is) is similar in function but with a better housing to protect from rain and corrosive elements and with lube-for-life bearings, so only minor periodic maintenance is needed to oil the chain and inspect for ratchet wear and loose bolts.

Figure 6. Newer design of ratcheting mechanism.

Figure 6. Newer design of ratcheting mechanism.

The ultimate failure mode for the old manure spreader turned out to be a mix of corrosion and ineffective lubrication. As illustrated in Figure 7, the older design had the manually greased, difficult-to-reach, open-rear spreader bearing mounted on sheet metal that was in an area severely contaminated by manure itself. The newer design (

see Figure 8) has lube-for-life bearings sealed from contamination and mounted on an eighth inch backing plate that easily could be replaced were it to corrode badly.

Figure 7. Old rusted bearing.

Figure 7. Old rusted bearing.

Figure 8. New bearing assembly.

Figure 8. New bearing assembly.

Clearly manure spreaders aren’t designed by rocket scientists, otherwise they would all be made of titanium or perhaps a mix of aluminum, stainless steel and composites. All bearings would be sealed for life. The cost of the thing might be greater than $100,000.

Nevertheless, the “manure-spreader scientists” have taken the lessons learned in the STLE trends report to heart. The new designs represent another victory for practical-minded tribologists. The result: a relatively inexpensive machine with significant moving parts that still operates reliably in a very harsh environment day after day with minimal maintenance.

Bob Gresham is STLE’s director of professional development. You can reach him at rgresham@stle.org

Bob Gresham is STLE’s director of professional development. You can reach him at rgresham@stle.org.