Small and Mobile: The future of on-site oil analysis

Josh Fernatt, Contributing Editor | TLT Technology August 2013

Developing technologies are enabling equipment managers to take the lab to the sample instead of the other way around.

KEY CONCEPTS

• Traditionally, equipment managers take an oil sample and send it to a lab for analysis, a process that can take several days.

• Emerging technologies are allowing equipment managers to perform on-site oil analysis in real-time.

• New options include a handheld device, a portable oil analysis machine that can be stored in a car or truck and inline sensors.

IN A HYPOTHETICAL MAINTENANCE SHOP, manager John Smith and his crew are responsible for a fleet of earth-moving equipment. A major aspect of John’s maintenance program is assessing the lubricant health of his machines, so he periodically fills sample bottles with in-service oil and sends it to a laboratory across the country.

For maintenance shops and industrial sites without their own labs, this scenario represents the traditional way lubes are analyzed to review their makeup and identify potential problems— or simply to decide when to change the oil.

To get the best results from his chosen lab, John must first ensure that he collects a contamination-free oil sample. The laboratory’s available lubricant references also might differ from the oil submitted for testing. This can lead to a lack of comparable data and affect future test repeatability. Oil analysis is a necessary cost of business but an expensive one when you consider the frequency with which these critical tests need to occur.

Though the machines under John’s care are subject to various forms of wear and tear as they navigate through a job site, similar maintenance challenges are found in route-based or stationary maintenance scenarios where the machines never move. In both cases, the ability to test oil at the source can save time and money. Developing technology to meet these challenges has been high on the drawing boards of a handful of industry companies, each of which is taking oil analysis capabilities into the future.

THE POWER OF PORTABILITY

Today’s oil analysis laboratories exhibit the height of automation and rely on machines designed to be user-friendly even for those who come to the process with relatively little industry background or training. However, they generally are too large or too expensive for smaller maintenance programs to procure. Thus, a shift to portability and affordability in oil analysis is underway.

“Miniaturization and mobility really characterize where the industry is heading in terms of in-the-field oil analysis,” says STLE-member David Hilligoss, global account executive-industrials for PerkinElmer, an international corporation headquartered in Waltham, Mass., with locations in 150 countries. “Whereas the typical method for solving problems used to be approaching questions, obtaining a sample and then bringing the sample to the lab for analysis, engineers, testers and maintenance personnel now can take the lab to the samples.”

One such example of this portability shift is the FluidScan® developed by Spectro Inc., an oil analysis company based in Chelmsford, Mass. Easily carried wherever it’s needed, the machine applies infrared spectroscopy to analyze and identify the chemistry of a substance.

The challenge of developing a rugged machine that anyone could use to assess lubricant health was taken up by STLE-member Dr. Patrick Henning, chief technology officer for Spectro. Henning, who has a background in physics and spectroscopy, realized the potential of portable sensing technology for lubrication analysis while working on a research and development contract for the Department of Defense (DOD). “It became a passion for me,” he says.

The DOD tasked Henning’s team with creating a portable device to gather quantitative, conditional information on lubricants such as hydraulic fluids, engine oils, turbine oils and gear oils—minus the time and costs associated with submitting samples to a lab. “After we developed this technology, we needed a way to bring it to the marketplace.” To make that happen, Henning teamed with Spectro, a worldwide supplier of oil and fuel analysis instruments.

A major factor in creating a field-ready handheld or portable analysis device is eliminating the need for chemicals, including solvents and other hazardous materials. This allows the user to simply place a drop of oil in the machine and wait for the results. “You don’t need a jug of wash-down fluid or alcohol to clean the system before the next sample,” Henning says. “You just wipe your sample down and go to the next one.”

The FluidScan has sensitivity comparable to lab-based Fourier Transform (FT-IR) spectrometers.

“This is a whole bunch of data crammed into a very small box,” says STLE-member Ray Garvey, P.E., CLS, an engineer with Emerson Process Management in Hinsdale, Ill., holder of 20 U.S. patents associated with oil analyzers, infrared thermography, machine monitoring and composite structures. “To know what it means, you have to know what reference oil you’re comparing it to and what infrared spectroscopy analysis method should be used. To get repeatable results, you have to have the correct reference identified, and you always have to select the same analysis method. By uploading route information to guide the operator from point to point, this handheld infrared spectrometer gets exactly the reference and method that it needs for every oil,” says Garvey of the FluidScan.

The following criteria can be measured by today’s portable devices:

• Total Acid Number

• Total Base Number

• Oxidation

• Nitration

• Sulfation

• Incorrect Lubricant

• Additive Depletion

• Soot

• Glycol/Antifreeze

• Water

The handheld Spectro FluidScan (Courtesy of Spectro, Inc.)

Another example of powerful portability is PerkinElmer’s Spectrum Two™ IR. The Spectrum Two is about one quarter the size of traditional FT-IR instruments but provides the same performance capabilities as a bench-top FT-IR. “Users can take it anywhere they need to go to test lubricants and oils on-site,” says Hilligoss.

The Spectrum Two™ IR (Courtesy of PerkinElmer)

The Spectrum Two can analyze lube oxidation and nitration and also can spot water, fuel or glycol contamination—telltale signs of an impending mechanical failure.

“It’s designed so a technician can put a sample in a cell, and the software will be specific to whatever needs to be tested and do the rest,” Hilligoss explains. “We’ve worked to make the technology more user-friendly for testers, mechanics or maintenance staff with even the most basic level of scientific understanding.” Portable and handheld devices like the Spectrum Two and FluidScan typically have few buttons and offer touchscreen interfaces, further increasing their ease of use.

A major goal of portable oil analyzers is providing technicians and engineers with the ability to generate top-quality results without sending samples to a lab. “You shouldn’t have to treat the data any differently if you’re in the field,” Hilligoss says. “We want the field tests to produce the useful data that analysts in a lab are accustomed to seeing. It is critical to have data generated from field testing match what the lab needs and is accustomed to analyzing for the sake of efficiency and time.”

A lot of money and time also can be saved through early detection, which could mean the difference between replacing the oil and replacing an entire machine. “A lot of visual inspecting is happening, but actual sample analysis is much less commonplace,” Hilligoss says. “All types of companies could benefit from having this technology, whether they are inspecting wind turbine gearboxes, generating power or inspecting systems.”

SCRAPPING THE BOTTLE

In a typical route-based maintenance program, oil samples are drawn from each machine in the route and either carried to a workbench for testing or sent to a laboratory. As part of a new oil analysis system for stationary machines, Los Angeles-based Analysts, Inc., is beta testing a program that combines data from sensor technologies, on-site instruments like the FluidScan and Spectrum Two and lab data.

“This essentially allows the user to combine and manage all his data in a single system,” says STLE-member Cary Forgeron, CLS, national sales manager for Analysts, Inc.

Like Spectro and PerkinElmer, Analysts has found that mobile and in-house technologies like the FluidScan, Spectrum Two and inline sensors are stepping into larger roles on the oil analysis stage. “The most important thing is the data and the interpretation of that data,” Forgeron says. “We’re looking at it unconventionally in that we don’t have to run all your tests for you, but we can provide a platform that houses all that data.”

Inline sensors send readouts to Analysts, Inc.’s LIMS software. (Courtesy of Analysts, Inc.)

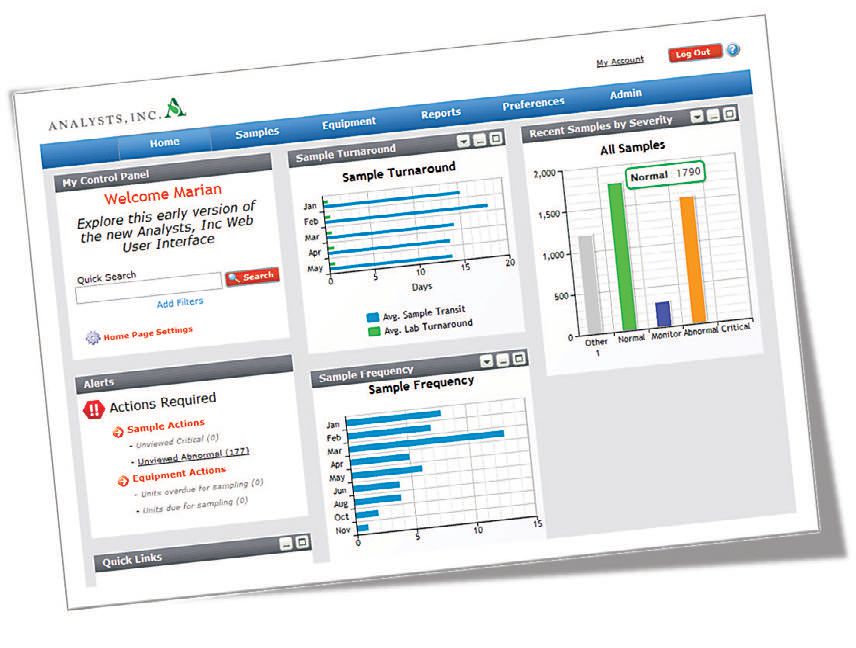

“The biggest complaint we have heard from our customers doing on-site testing is that they couldn’t link the testing they were doing with the testing we were doing,” says Forgeron. To address these concerns, Analysts has spent the last three years developing a new Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) platform. During the development phase, it became evident that smaller facilities around the world must test on-site because they can’t get samples to a lab. The vision for a new LIMS platform is to provide a way for facilities to import and log samples for each test performed in order to generate a chronological sequence of results and machine health.

One solution Analysts is working on is merging its software component with inline sensors. “A laboratory in Italy that we do a lot of work with has developed three sensors, and we have incorporated them into what we’re doing here,” Forgeron says. “The three parameters they measure are viscosity, water content and wear particle concentration.”

With inline sensors installed, maintenance technicians can program automated checks on any schedule they choose to build a bank of data points for each machine. The inline sensors can be installed on housings or through bypass and will ping data back to the computer at any specified interval.

The ability to combine data from inline sensors and other on-site testing devices could provide effective oil analysis at a fraction of the cost of sending samples to a lab, according to Forgeron. The cooperation between a LIMS system and portable devices also can tie in with services offered by labs. For example, on-site data could be managed and mapped at the ground level, or it could be shared virtually with a full-scale lab for additional analysis. “A lot of feedback we got was that the customers can perform the analyses on-site, but there may not be an expert to interpret the data,” Forgeron says. “It’s like sending a sample to the lab, but the lab already has the data and is not performing any tests, they’re just looking at the data.”

This version of lab analysis can offer a clearer window into a machine’s overall health, as the analyst can take into consideration the wealth of data points collected over a period of time, as well as historical trends, rather than just a single sample from a single day. In its most final iteration, Analysts’ envisions its LIMS platform automatically pulling data from a wide variety of on-site devices like the FluidScan that can be posted in individual files for each piece of equipment tested.

A sample readout from Analysts, Inc.’s LIMS platform (Courtesy of Analysts, Inc.)

LOOKING AHEAD

Fast-forward a few years and John Smith is still successfully keeping his quarry’s machines up and running smoothly. However, instead of carrying bottles to capture a sample of oil, he now takes a portable oil analyzer straight to the machine to gather data on the spot. Back at the shop, he syncs his analyzer with the company’s LIMS and records his findings. If he needs a deeper level of analysis, he can instantly transfer his collection of lube data points to the lab in an email. No muss, no fuss.

“We are constantly evaluating technology and service options to address our customers’ needs around monitoring the condition of their equipment engines,” says Andrea Jackson, vice president of environmental market and business for PerkinElmer. “Whether producing a small instrument to perform rapid testing or building it into a piece of machinery.”

Though Forgeron reports that Analysts will be testing the functionality of the LIMS platform and its abilities as an alternative to sample sending very soon, the technology will not likely be released in final form for another two years. “What we want to do is collect data over a one-year period and see how that goes,” says Forgeron.

For Henning and the Spectro team, reports of the FluidScan’s portability and use in both fleet and static maintenance programs are very positive. “The ruggedness of the equipment and the ability for an untrained operator to guide the measurement is really what we strive for to make the field equipment successful,” Henning says. “The idea was that a laboratory is always going to be there, because you need that surety and validation when a problem is discovered, but [portable devices] could tell you when something is wrong and give you an idea of what is wrong.”

Josh Fernatt is a freelance writer who can be reached at josh.fernatt@gmail.com.