The Five Levels of Fleet Maintenance

Josh Fernatt, Contributing Editor | TLT Webinars March 2013

A fleet manager for the Virginia DOT offers a goal-driven program that has passed the hardest test of all—life on the streets.

KEY CONCEPTS

• Fleet equipment requires regular maintenance performed at optimal levels using multiple strategies.

• It’s critical to have all possible information you can have for your machines.

• A common mistake is applying the same maintenance strategy to everything.

WEBINARS: A NEW SERIES FROM TLT

This article is the third in a year-long series based on Webinars originally presented by STLE University. In some cases, the Webinar presenter will author the article, and in others, like this one, the Webinar is adapted by a TLT writer.

Carlton D. Stevens, CEM, spent 15 years in the auto parts, fleet and heavy equipment industry before joining the staff of the Virginia Department of Transportation as district equipment fleet manager for the 10-county Lynchburg District almost 20 years ago. He is a member of the Association of Equipment Management Professionals, is a Certified Equipment Manager and a member of the Association of Maintenance Professionals. The Virginia Department of Transportation Lynchburg District was awarded the Program of the Year for 2007 by Uptime magazine and was featured in its story, the “Best Mobile Lubrication/Oil Analysis Program.” The department also was featured in the May 2011 issue of Lubes’N’Greases magazine in an article titled, “Oiling the Old Dominion.” You can reach him at Carl.Stevens@VDOT.Virginia.gov.

STLE University has sponsored dozens of Webinars and podcasts on a wide range of technical topics. To see Carl Stevens’s Webinar in its entirety, review all STLE University offerings and view the lineup of future events, log on to www.stle.org. Webinars are $39 to STLE members and $59 for non-members.

Carlton Stevens

ON ANY GIVEN DAY, you can observe a variety of machines and their operators working on America’s highways, industrial sites and construction zones. From bulldozers to cranes to delivery vans, equipment fleets are the backbone of private corporations and government entities that rely on their capabilities to carry out day-to-day operations.

Fleet equipment requires regular maintenance to perform at optimal levels. Today, a successful maintenance strategy goes far beyond taking action at the moment something breaks. The men and women who nurse these machine armies back to health apply data-gathering skills and experience to predict and prevent mechanical failures before they occur.

In a June 2012 Webinar presentation sponsored by STLE University, Carlton Stevens, fleet manager for the Virginia Department of Transportation’s Lynchburg District, shared his thoughts in a presentation titled The Five Levels of Fleet Maintenance. In the most effective and efficient fleet maintenance programs, the five levels are mixed and matched to identify the best strategies for different maintenance needs.

“In the 21st Century, a successful program will be measured by how many failures never occur,” says Stevens, a Certified Equipment Manager (CEM). “If you have a good preventive maintenance program, you will be relatively successful.”

1ST LEVEL: FAILURE MAINTENANCE

Regarded as the most costly and least efficient of the maintenance levels, failure maintenance happens once a machine’s condition hits critical. There’s no breakdown prevention—only reaction. As such, production time is lost while the broken machine sits idle in a repair bay. Because the failure has probably reached a catastrophic level, the cost of parts and labor can soar.

However, says Stevens, there are times when just running the machine to failure makes more sense than spending time and money to repair it. In the case of a relatively inexpensive piece of equipment (Stevens gave the example of a $300 chainsaw), a maintenance program may save money in labor hours and parts by just purchasing a new one. However, with major pieces of equipment where replacement costs can reach tens of thousands and even hundreds of thousands of dollars, operating these machines until they fail can be extremely costly.

2ND LEVEL: SCHEDULED MAINTENANCE

Scheduled maintenance can extend component life, as machines are serviced based on a set time or mileage schedule. However, this level does not account for the actual amount of machine use and can result in over-maintenance or even under-maintenance for heavily used equipment.

Scheduled maintenance has its place in routine tasks that are essential for extending machine life, like oil changes, cleaning and routine adjustments. However, because the manufacturer’s specifications may not differentiate for higher usage levels, performing only scheduled maintenance could be overly conservative.

3RD LEVEL: PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE

Preventive maintenance is the first maintenance strategy in which data is collected to predict when machine components may be at risk and the causes behind those failures. Preventive maintenance might still follow service schedules or mileage counts, but it diverges from reactionary maintenance in favor of a system where technicians perform root-cause analyses, observe diagnostic checks and address potential issues before they escalate.

Preventive maintenance practices focus on replacing machine elements before they reach the end of their useful life. Says Stevens: “In many cases, even preventive maintenance is more ‘reactive’ than ‘proactive.’ It’s a relatively good approach, but it’s still not the highest level of maintenance.”

4TH LEVEL: CONDITION-BASED MAINTENANCE

In condition-based maintenance, technicians examine the machine before and after operation to determine how certain elements are wearing and if signs indicate an impending failure. Condition- based is also the level of maintenance where fluid analysis begins to appear.

“When the machine comes in, you’re going to go through your normal checks, but you’re starting to look at fluid analysis, hydraulic, coolant, fuel, oil—everything that gives insight into the actual health of that machine,” says Stevens. “You start to evaluate potential failures that are beginning to show themselves that could lead to a catastrophic failure.”

5TH LEVEL: PREDICTIVE MAINTENANCE

Predictive maintenance combines elements of preventive and condition-based methods to form a system in which technicians observe and collect data of trends that occur during a machine’s lifespan. These data are based on operators’ daily reports, hydraulic and coolant fluid analyses as well as fuel and oil evaluation. Performing vibration and infrared analyses also can provide insight into a machine’s overall health. As patterns in these data emerge over a machine’s history, it becomes possible to forecast potential problems and protect against failures.

“The key with predictive is knowing how to interpret what the data is telling you,” explains Stevens. “Of course if there is a failure, then a failure analysis should be conducted. Although we are primarily focusing on maintenance, this information also can be applied to overall fleet management techniques like life cycle cost and specifications.”

Because the collection of comprehensive equipment data makes up a large portion of predictive maintenance, one could assume that machines that aren’t used often generate less data and so make predictive maintenance difficult. Not so, according to Stevens. “Predictive maintenance is essentially applying all the techniques from the previous levels,” he says. “You may not have as much data to review, but what you have may be very enlightening. It may be as simple as the operator pre-trip inspection or the fluid analysis results.”

A brine trailer being inspected and prepared for the winter season.

NINE GOALS

Fleet maintenance seems to comprise two simple goals: keep equipment operational, and repair it when it breaks. But there’s more to consider, especially when company profits or taxpayer money is on the line.

The first goal to consider when developing an effective maintenance program is what Stevens calls preventive maintenance and maintenance prevention. The initial part relies on the ability of preventive maintenance to preserve equipment as long as possible by being aware of warning signs and replacing parts before they fail. It also encourages inspections to prevent unnecessary maintenance.

“People in the fleet business have always heard, ‘We’ve been doing it that way because that’s the way we’ve always done it,’” says Stevens. “That’s the type of thing you need to get away from. Instead, start doing more detailed inspections, educating your operators on the correct way to operate a machine.”

The second goal is to find hidden resources that will help your maintenance plan progress smoothly. Oftentimes, these are the technicians themselves. “Problem-solving and elimination, improvements to maintenance where practice and processes have been—we have to be able to include folks in every aspect of what we’re doing to get their input,” says Stevens.

Another facet of the second goal is consolidation. One example was led by the Lynchburg VDOT district, which streamlined a program that previously stocked 120 different lubrication products. By determining the items most frequently used in the district’s machines versus those that may have been superfluous, the district reduced the total number of lubricants in use to 16, saving a significant amount of money and time.

Goal Three is work management. “For world-class maintenance performance, it is generally considered that 70% of all work should be planned and scheduled no less than 24 hours ahead,” says Stevens. “Scheduling a job is not the same as planning it. You’ve got to plan it before you can schedule it.”

To better plan, Stevens suggested observing the Three Cs—complaint, cause and cure. The Three Cs verify the initial complaint, what caused it and what cured it. “This is good information to hold onto and record in your work order system, because you’ll probably have to refer back to it at some time, and it will already be there,” he says.

Goal Four takes the planning stage one step further into job execution. Because machine downtime is costly, repairs must be completed correctly the first time. “Maintenance jobs have to be done in a quality manner with efficiency and timeliness,” says Stevens. “A job well planned is well on the way of being a job well done.”

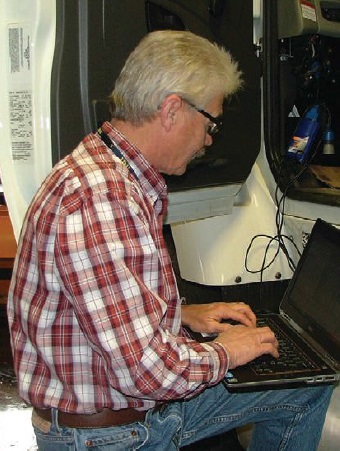

A VDOT shop supervisor performs a running diagnostic test on a tandem dump. The majority of new vehicles and equipment now have onboard capabilities that can be accessed by a laptop.

To achieve Goal Five, communication and teamwork between maintenance staff and machine operators are crucial. This partnership makes data gathering for each machine a simpler, more comprehensive process. After all, operators are in close proximity to the machines for extended periods of time while they are running full bore. This gives them an opportunity to note strange noises or other unusual symptoms, which they can relay back to the shop. “It’s a good opportunity to identify operator maintenance activities,” says Stevens. “It makes sure everyone is on the same page and no one misses anything.”

Another pillar in building an effective fleet maintenance program is learning from and managing the three stages of equipment failure: physical, functional and catastrophic. Goal Six, failure management, refines the practice of gleaning valuable information from a machine in the beginning stages of breakdown. Physical failure is heralded by the appearance of noticeable warning signs that something is amiss in the machine. These signs include fluid leaks, temperature changes and noises or corrosion and point to an eventual loss in functionality if not promptly addressed. In the next stage, functional failure, the machine begins to lose efficiency and perform below its specifications. If allowed to continue, a functional failure could lead to a catastrophic failure and the potential loss of the machine.

“Your operators are your eyes and ears—they know what that machine is doing every day and they are your first line of defense in any maintenance program,” says Stevens.

Goal Seven is making the most out of what may be scarce funding, especially in a government operation. Purchasing decisions need to account not only for upfront acquisition costs but also estimates of upkeep costs over the machine’s life.

Developing win-win partnerships with equipment suppliers is also important, says Stevens. “Good supplier networks are an invaluable source. You can count on these people not only to supply your parts, but as much as anything else they will provide information that will help you manage your fleet most efficiently.”

Establishing win-win partnerships between maintenance and operator staff through training programs that pinpoint assessed needs is Goal Eight. Training programs should focus on the knowledge needed to perform well every day, with elements of continuing education to keep the workforce up to speed on emerging technologies and techniques. Keeping machine operators and maintenance technicians in the loop on program successes and failures is also vital for establishing a unified team of management and workers.

Goal Nine entails gathering technical information and documentation data and providing that information to maintenance team members. This way, each member has access to equipment specifications at the instant they’re needed. “We require that any time we purchase a new machine, we are given access to the service network of the company that we buy the machine from,” says Stevens. “It’s very important to have all the information you could possibly have for all your machines.”

Fluid analysis is integral to developing a good preventative maintenance program.

CONCLUSION

“One of the biggest mistakes folks make is trying to apply the same maintenance approach to everything,” says Stevens. “Do pilots apply the same flying techniques to all aircraft they fly? No, that’s why they must be checked out in every different class of aircraft.”

The same applies to establishing an efficient and effective fleet maintenance program. Paying close attention to every detail, from routine equipment checks and fluid analysis to open communication with machine operators, ensures that America’s equipment fleets keep rolling.

Photos courtesy of Carl Stevens, Virginia Department of Transportation.

Josh Fernatt is a free-lance writer who can be reached at josh.fernatt@gmail.com.