Any suggestion within boundaries

Evan Zabawski | TLT From the Editor April 2012

Reader response prompts topic – sort of…

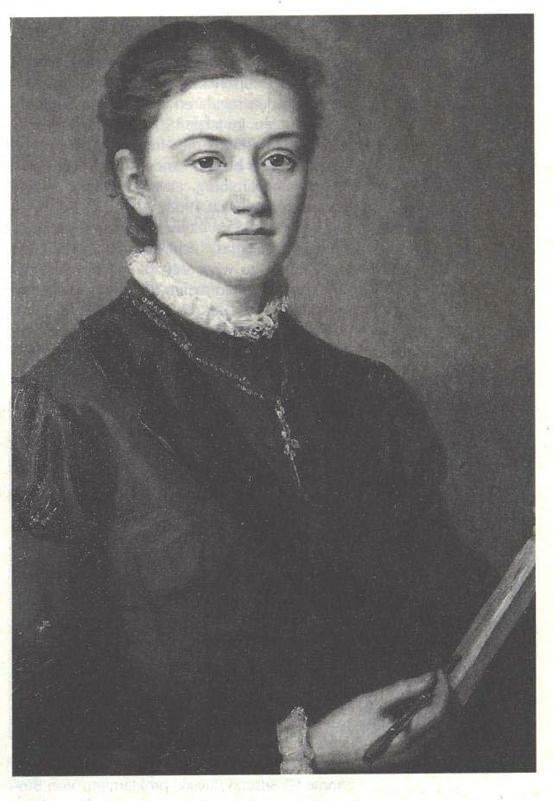

Agnes Pockels’ findings formed the basis for the study of surface films.

RECENTLY I RECEIVED AN EMAIL FROM TLT TECHNICAL EDITOR PAUL MICHAEL, an STLE-member and research chemist at the Fluid Power Institute at the Milwaukee School of Engineering in Milwaukee, Wis. His note read: “You sure do a great job with TLT. I bet you could write an interesting little piece on who coined the term ‘boundary lubrication.’ I’m curious.”

Eager to reply, I looked up the term and discovered it was coined by British chemist and biologist Dr. (later Sir) William Bate Hardy (1864-1934) at a Bakerian Lecture in 1925 titled, “Boundary Lubrication— Plane Surfaces and the Limitations of Amontons Law.” Sadly, there really wasn’t much else of further interest about Dr. Hardy to write about.

One small fact that caught my eye, however, was that he was the recipient of the Laura R. Leonard Prize from the Kolloid- Gesellschaft (Colloid Society) in 1928. The little-known award was most famously given to Agnes Pockels in 1931 “on her quantitative investigation of the properties of interfaces and surface films, and for the methods she used, which have since become fundamental in modern colloid science.” It is her story that offers an excellent topic for this month’s column.

Born in Venice, Italy, in 1862, Agnes Pockels moved to Braunschweig, Germany, at the age of nine where she completed her schooling six years later. At age 18, while performing household chores, Agnes looked into a sink of greasy water and observed the anomalous behavior that different impurities had on the surface tension of the water. Such was the beginning of her informal research that would see her develop a slide trough, which she called Schieberinne (literary: shift trough) for measuring surface tension. Armed with this device, Agnes collected observations during the next 10 years.

In 1891 Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt) published a paper on the properties of water surfaces. Agnes read this paper and was inspired to write to him to share her own concurrent observations. Upon reading her letter, Lord Rayleigh had her findings translated and forwarded them to the journal

Nature asking for them to be published. At age 29, Agnes Pockels, without formal education and using “homely appliances,” had her research published in a prestigious journal.

Her findings, which summarized how surface tension changed with area and contamination, formed the basis for the study of surface films. She would publish 13 more papers during the next 35 years while remaining a spinster and caring for her sick family.

One of her papers discusses the calming effect of oil on the surface of water—a topic discussed in my March 2011 column. This effect was observed by Benjamin Franklin and later quantified by Lord Rayleigh, who calculated the thickness of the film by knowing the volume of oil added to a given surface area. These calculations would go on to prove Avagadro’s number.

An American physicist named Irving Langmuir developed her Schieberinne further into the so-called Langmuir trough and later hired a student named Katherine Blodgett to assist in his research along the same lines. Together they would discover the eponymous Langmuir-Blodgett film, comprised of one or more monolayers of organic material that deposits from the surface of a liquid onto a solid. This accurate and homogenous layering process, using a device now called a Langmuir-Blodgett trough, has been used to create anti-reflective coatings on glass.

In 1932 Agnes Pockels was honored with the aforementioned award and became the first female recipient of a doctorate degree from the Technical University Braunschweig when they bestowed an honorary degree on her 70th birthday. Irving Langmuir would receive the Nobel Prize in chemistry that same year.

The Langmuir-Blodgett trough is still used today as an experimental tool for boundary lubrication.

Evan Zabawski, CLS, is the senior reliability specialist for Fluid Life in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. You can reach him at evan@fluidlife.com

Evan Zabawski, CLS, is the senior reliability specialist for Fluid Life in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. You can reach him at evan@fluidlife.com.