Managing a lubricant changeover

Stacy Heston | TLT Best Practices March 2012

Start small, control product compatibility and establish a timeline with proper documentation.

KEY CONCEPTS

•

If improperly managed, changing suppliers can wreak havoc on a stable lubrication and oil analysis program.

•

When switching lubricants, be aware that there is a difference between comparable products and compatible products.

•

The oil analysis laboratory should be notified about the status of the conversion for each individual component.

FROM TIME TO TIME, COMPANIES WILL MAKE EXECUTIVE DECISIONS to change lubricant suppliers. These changeovers can wreak havoc on a stable lubrication and oil analysis program. It is important to have a plan of action in place with a focus on steps and considerations from an operations perspective, as well as the inclusion of the oil analysis laboratory. This would include considerations of the component sump size, criticality and component inclusion in an oil analysis program.

When establishing the specific product to change over to, each component’s lubricant requirement should be evaluated to determine if the proposed lubricant meets each component’s needs. A one-to-one lubricant conversion is not advisable, as one manufacturer’s product might currently meet all needs and required specifications while the comparable and compatible manufacturer’s product does not. The current component grouping for lubricant application may be met by the current product, but the proposed products may require a shift in the component grouping to ensure adequate lubricant properties.

With the introduction of new lubricants on site, it is vital to understand the difference between

comparable products and

compatible products and identify which type these new products will be. Change over to products that are compatible requires less management with regard to mixing but can affect oil analysis results unless the changeover is communicated to the oil analysis laboratory. For lubricants that are comparable and not compatible, the management of the changeover must be more vigilant to ensure the new and old lubricants are not mixed and that changeover occurs at an optimum time.

Comparable products are likened to one another and share similar characteristics, allowing use in components of similar make, model and application. Compatible products do not necessarily need to be comparable because compatibility relates more to the lubricant chemistry. Compatible lubricants can exist or occur together without conflict of the base oil and additive package. Knowing the compatibility of the new lubricants with existing lubricants will affect the specific tasks and procedures utilized for changing the lubricant in a component. It also will affect the steps required for managing the overall changeover, the inventory levels and packaging requirements.

Component Lubricants

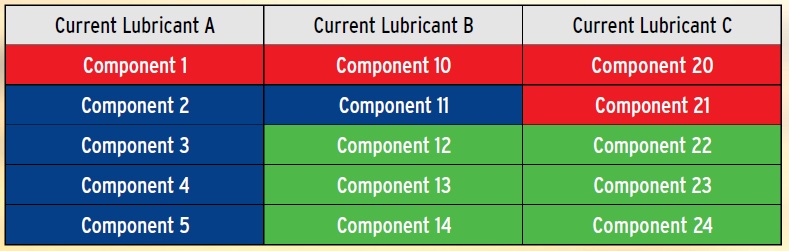

Figure 1. Proposed lubricants are demonstrated through color-coding. This evaluation should follow industry standards for the determination of lubricant requirements, which includes looking at operating speeds, temperatures, contamination, vibration, load, etc.

Figure 1. Proposed lubricants are demonstrated through color-coding. This evaluation should follow industry standards for the determination of lubricant requirements, which includes looking at operating speeds, temperatures, contamination, vibration, load, etc.

Once the lubricant requirements are established, the proposed lubricant changes should be documented, and the current and proposed lubricant should be reviewed for compatibility. Additional information—such as component manufacturer and model, sump size and current and proposed lubricant cost per gallon—also should be compiled.

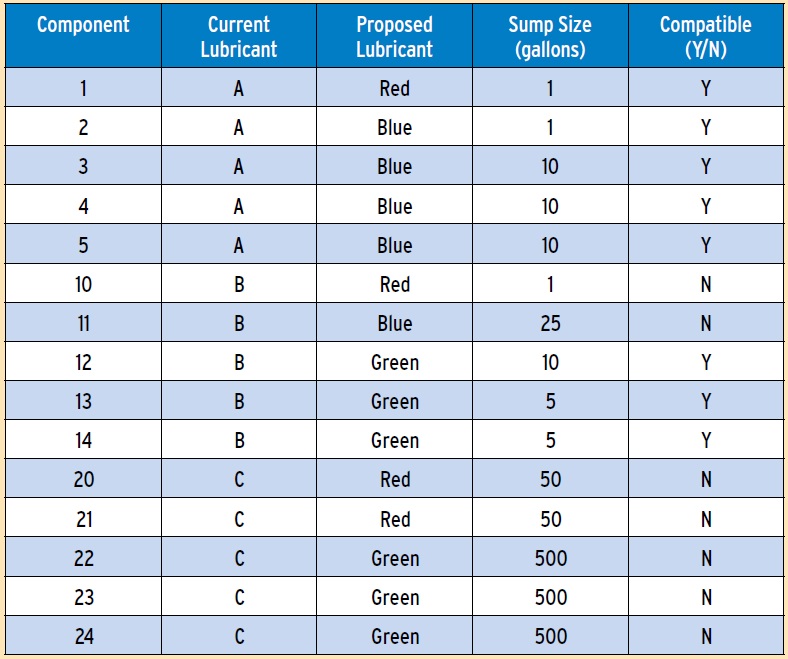

As stated earlier, converting to a non-compatible product requires additional steps to avoid component and lubricant failure. In Figure 2, components 10, 11 and 20-24 have a proposed lubricant that is not compatible with the current lubricant. Before the new lubricant can be introduced for these components, a full oil drain and flush of the component needs to be completed to ensure no residue remains. Depending on the lubricant base oil and additive packages, incompatible residue can have detrimental effects to the new lubricating properties. In some cases, there can be additive film interference where the residual additive film remains in place and is slowly overtaken by the new additive film. In extreme cases, where ester and mineral base oils are converted, the residue can react to such an extent that the oil forms a gel in the sump. Lubricant compatibility should be verified and acknowledged by the new lubricant supplier.

Figure 2. Current and Proposed Lubricants

Figure 2. Current and Proposed Lubricants

For small sumps, converting incompatible lubricants is a simple and inexpensive task. During the next scheduled oil change, a sump is easily drained, flushed and topped up with the new oil. Once this conversion is complete, CMMS information, lubricant identification tags and other documentation should be updated to reflect that the component is now using the new lubricant. Documentation should not be updated until the conversion is complete.

With larger sumps, such as components 22, 23 or 24, the cost of converting the sump is higher. If a supplier agreement has been made at the corporate or plant level, does it allow for using a different supplier for specialized applications, or is the agreement rigid enough to require the use of a supplier equivalent? If the supplier agreement allows for the use of non-supplier lubricants, maintaining the current lubricant is most likely the best course of action, assuming the current lubricant meets the required lubricant specifications.

If the current lubricant is not up to par, conversion to the proposed lubricant is necessary. There are a few different approaches that can be utilized to convert the lubricant, and the chosen approach is dependent on how the plant operates and what the overall goal is. The first approach, and possibly most costly, is to simply set a date to drain, flush and top up with the new oil. This approach is beneficial if there is a stringent timeline for converting all assets to the new lubricants. Manpower availability also should be looked at to ensure properly trained lubrication technicians are available to perform the conversion within the specified timelines.

A second approach for converting large sumps looks to maximize the usage of the current oil through the monitoring of the lubricant properties. If the timeline for conversion for the larger quantity components allows for the lubricant’s remaining useful life to be consumed, the state of the lubricant properties (oxidation, neutralization number, viscosity, etc.) should be used to determine when the oil is ready to be converted. This approach could extend a conversion timeline to multiple years if other lubrication maintenance tasks are performed.

For components being converted to a comparable and compatible lubricant, a full oil drain, flush and top up may not be required. These components would be topped up on a normal inspection interval with the new lubricant until an oil change occurs. For smaller components with set oil drain intervals, there will be a time that the two lubricants must coexist until the drain occurs. For larger sumps subject to oil analysis, a set oil drain does not exist. The two lubricants would presumably have to coexist for a longer period until such time the oil analysis results dictate the need for an oil change.

EFFECTS ON OIL ANALYSIS

Mixing the lubricants in a sampled component can wreak havoc on an oil analysis program. It is critical that the addition of the new lubricant to a component be documented within the CMMS, work order, lubricant listings, etc. In addition, the oil analysis laboratory should be notified about the status of the conversion for each individual component (full change to new product, mixed). Typically this information can be provided on the sample label.

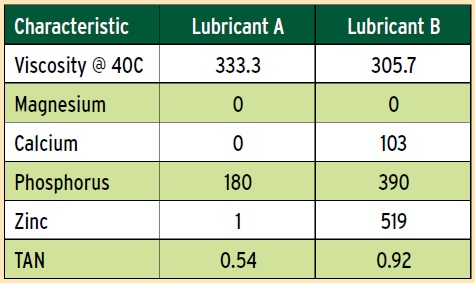

When an oil laboratory receives a sample, the workers there do not know what is taking place at the site level. They know as much as what is on the sample label and in the laboratory information management system. Once test results are complete, the documentation on lubrication will affect any subsequent recommendations. If a full lubricant changeover is completed without notifying the laboratory, inaccurate recommendations will result due to a shift in the lubricant characteristics (

see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparing Lubricant Characteristics

Figure 3. Comparing Lubricant Characteristics

These lubricants share similar operational characteristics as described on their product data sheets and might or might not be compatible. However, it is important to note the differences between the two. These results are indicative of some of the viscosity grade, additive package and neutralization number and are generally constant results for a lubricant. A shift in these results would be reason to flag an oil analysis result and recommend corrective action without knowledge of a lubricant changeover. If Lubricant A were to be topped off with Lubricant B, the results would start to show an increase in phosphorus and zinc with specific results dependent on the ratio of Lubricant A to B.

THE NEW INVENTORY

Once the approach to lubricant changeover has been established, the issue of inventory needs to be addressed. The proposed lubricant list by components needs to be finalized and updated to reflect any changeover issues that have been addressed such as continued use of current lubricant. With the finalized lubricant assignments in place, the new inventory levels need to be determined. Rule of thumb varies from 5%-10% of total machine charge as a starting point to the use of current consumption rates. However, consumption rates may not be readily available if there is a significant shift in the number of lubricants required, as well as the ratio of lubricant usage.

As the current lubricants are phased out, the new lubricants will be phased in and each lubricant will require its own storage space or tank. If bulk storage is in use, it is recommended that the current and new lubricants not be mixed. This might require temporary use of drum storage or other packaging types until the bulk lubricant has been completely consumed. At that time, the bulk storage tanks should be flushed using the same procedure as any component to ensure that residual lubricant does not remain.

For instances where prepackaged quantities (five-gallon pails, quarts, etc.) are in use, the additional purchase of current lubricants should cease, and the possibility of returning unused lubricants should be investigated. In some cases, suppliers might offer to buy back lubricants but could require the payment of a restock fee. Regardless, any outstanding stock of current lubricants should be consumed.

DEVISING A TIMELINE

As with any lubrication program, a key goal is minimizing the number of lubricants on site. Therefore, during a lubricant changeover, a short timeline is a key goal. When determining a timeline, the total number of lubricated components should be considered and a breakdown by lubricant performed. Introducing one new lubricant at a time focuses attention on a core group of components, minimizes confusion brought on by major implementations and reduces the total number of lubricants handled on site.

The key to lubricant changeover is to start small: Which lubricant change affects the least number of components? A successful changeover of a small number of components that are not included in the oil analysis program allows for the development of changeover management and increases the confidence level of all personnel affected by this type of implementation. Once one lubricant has been successfully introduced and changeover started, additional lubricants can be brought on as necessary.

A timeline for changeover should not exceed the one-year mark unless the components are of a large sump volume or part of the oil analysis program. The changeover should begin with a specific component type, size and lubricant requirement. Once complete, the next component type or size should be converted until the new lubricant is implemented; then repeat this implementation with the next grouping until the new lubricant product has been implemented for all affected components. After the completion of one lubricant, the next lubricant for changeover should be selected.

It is not necessary to convert only one lubricant at a time if a lubricant program is well structured and managed. However, an implementation plan needs to be clearly established and documented to act as the road map.

Changing oil is a time-consuming task. With variation in component sump sizing, variation in the time requirement per oil drain also should be accounted for. During the first round of changeovers, as mentioned in the previous paragraphs, the relationship between the sump volume and time required to complete the drain, flush and top up should be documented so time projections are established for future changeovers.

For example, if a 10-gallon component requires 60 minutes, then it is extrapolated to be six minutes per gallon. A 50-gallon sump might require five hours to complete a changeover. Calculating an average time for multiple components yields a more accurate time per gallon result. Having a labor time associated with each component and subsequent asset or lubricant type aids in scheduling and timeline development.

CONCLUSION

To summarize, the required steps start with a review of lubricant requirements for each component. Avoid converting lubricants based on the lubricant in use. Lubricant suppliers should verify compatibility of proposed lubricants with current lubricants, and steps should be taken to avoid mixing incompatible products. For small-volume components, the set oil drain interval should be followed for conversion. For large-volume components, oil analysis should be utilized to determine when to convert the oil in order to maximize the oil life.

As analyzed components are converted, the oil laboratory should be notified to ensure data interpretation reflects acknowledgement of these changes. Inventory level modification should be implemented to reflect a decrease in current lubricants and increase in proposed lubricant while maintaining a first-in, first-out rotation. Timeline and scheduling should be managed within parameters prescribed by site management while following general guidelines to avoid possible cross contamination and documentation errors.

Stacy Heston is a lubrication subject matter expert and provides reliability-centered lubrication program development services and training to a wide variety of customers. Among her professional credentials are STLE’s CLS and OMA I certifications and the International Council of Machine Lubrication’s Machinery Lubrication Technician I & II certifications. You can reach her at heston.stacy@gmail.com

Stacy Heston is a lubrication subject matter expert and provides reliability-centered lubrication program development services and training to a wide variety of customers. Among her professional credentials are STLE’s CLS and OMA I certifications and the International Council of Machine Lubrication’s Machinery Lubrication Technician I & II certifications. You can reach her at heston.stacy@gmail.com.